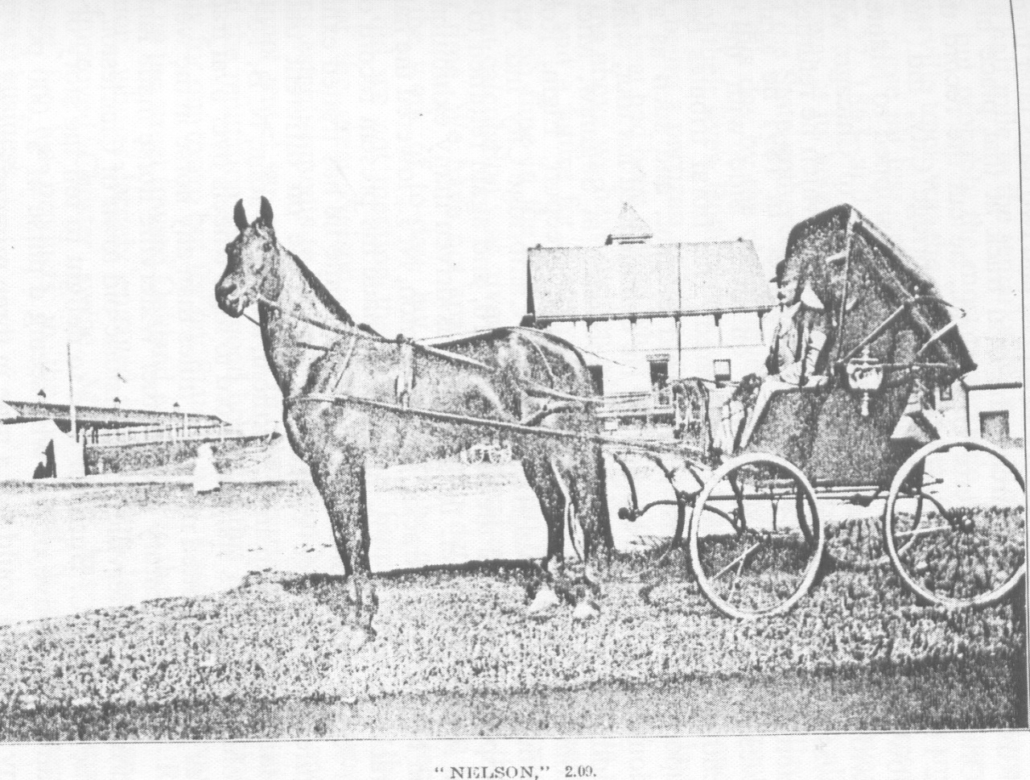

“Nelson” and his breeder Charles Horace Nelson, in a photo that appeared in The Centennial History of Waterville, 1802-1902, by Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore. The chapter on agriculture was written by E. P. Mayo.

This article is for people who enjoy an occasional glimpse into someone else’s life – nothing scandalous or earth-shaking, just odds and ends about the ordinary lives of people in another time. The main source is Henry D. Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history.

The Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 was first published in 1892, after what editor Kingsbury described as “two years of labor.” Simeon L. Deyo is listed as co-editor and there are 18 “Resident Contributors.”

In the introduction, Kingsbury thanks “twenty writers whose names these chapters bear,” “more than twenty hundred” people who contributed through correspondence or interviews or both and “the good people of Kennebec who have so kindly and faithfully cooperated with us.”

The initial edition, by H. W. Blake & Company, 94 Reade Street, New York, was limited to 1,600 copies. The last page is number 1273, and that number does not count the introduction, illustrations or instances in which pages have the same number followed by a or b. The result is a volume that measures 11 inches high, eight inches deep and almost four inches wide – a worthy companion to the family Bible that would have been conspicuous in many Kennebec Valley homes in 1892.

Although there is no evidence of other editions until recently, there are references on line to two-volume versions. In 2018 a 956-page paperback was published.

Kingsbury divided the work into two sections. Each of the first 15 chapters covers a specific topic, like land titles, military history, courts and the law and the medical profession. The rest of the book describes individual towns, giving most a single chapter, Waterville two chapters and Augusta three chapters.

Kingsbury and his contributors were not infallible. Later historians have corrected some of his information, probably because they have more resources and more time than he had. Nonetheless, the Kennebec County history is a valuable starting point. Many on-line displays quote the same comment: “This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it.”

Each chapter on a city or town ends with what Kingsbury labeled “Personal Paragraphs.” These profile an individual, or occasionally a family, who lived in the municipality in the 18th century. The number of profiles per chapter varies, depending partly on the size of the municipality.

The vast majority of those Kingsbury chose were men – your writer has not reviewed towns outside the central Kennebec Valley, but within the area has found only two women who deserved mention. Some were prominent citizens; at the end of the chapters on Augusta, publisher Edward Charles Allen (1849 – 1891) was described as “the wealthiest man of Augusta…[who] paid the largest personal tax.” (See the Nov. 12, 2020, issue of The Town Line for information on Allen’s publishing empire and its impact on Augusta’s growth in the 1870s and 1880s.)

James G. Blaine (1830-1893; United States Representative and Senator, Secretary of State, unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1884, called the Plumed Knight by his friends and the Continental Liar from the State of Maine by his opponents) got eight and a half pages of fine print, contributed in April 1892 by “his townsman and former business partner, Hon. John L. Stevens, United States Minister Resident, Honolulu, Hawaii.” (Blaine was profiled in the Aug. 20, 2020, issue of The Town Line.)

The majority of people to whom Kingsbury gave a few sentences or a few paragraphs were less exalted. Many were farmers, blacksmiths, small businessmen and the like. As a city, Augusta offered a choice of educated professional people, some of whose stories he told.

* * * * * *

Sidney native Henry Pishon, born in 1833, attended Vassalboro and Waterville academies and served as an acting ensign in the Navy for two years of the Civil War. In the 1860s and 1870s he served two short stints as chief clerk in the Maine secretary of state’s office.

When the Augusta post office and courthouse were built on Water Street between 1886 and 1889, Kingsbury wrote, Pishon was the “clerk of construction.” A United States treasury disbursement list for July 1889 found on line lists four local men involved in the project: Thomas Lambard clerk, Pishon foreman, Herbert G. Foster disbursing agent and Melvin S. Holway superintendent of construction.

If “p.d.” in treasury records means per diem, Lambard earned $6 a day, Pishon and Foster earned $4 and Holway was paid some (illegible) fraction, perhaps one-half “of 1 p. ct.” of an unknown amount.

Sereno Sewall Webster (1805 – 1893) was the descendant of four Nathan Websters and two John Websters. The first John Webster was born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1605. The second, Sereno’s father, was born in 1777 or 1778 and died in 1828.

(Kingsbury’s source called the 1605 John Webster a “free-man,” leading your writer to wonder if he was a former Black slave. Not necessarily; in colonial Massachusetts, a free man was anyone who had full civil rights. Some colonies, not all, required membership in the established church; land ownership was not necessary.)

Sereno was born in Gardiner, according to an on-line genealogy on the Find a Grave website. John Webster moved his family to Vassalboro in 1806, according to Kingsbury. Sereno held a “clerkship” in Washington, D. C., for nine years; in 1845, he married Mary A. Hayes (1821 – 1893) from Dover, New Hampshire. Kingsbury said the couple had three children; the on-line genealogy lists four, born between 1846 and 1857, Helen, Emeline, Sereno and Otis.

Sereno Clifford Webster, Sereno number three, was born in 1850 and died in 1919, according to the genealogy. He married Alice Etta Tracy; they named their first son Sereno Sewall Webster (1889 – 1980). Most members of the family are buried in Augusta’s Wall Cemetery, at 422 Riverside Drive.

The on-line search for Sereno Webster turned up yet another man with the same name: an obituary for Sereno Sewall Webster, Bowdoin Class of 1943, who died April 12, 2006, in Brunswick. The obituary says he was born in Augusta Aug. 9, 1920, graduated from Cony High School and after World War II service had a career as an engineer and surveyor. His wife, Eula Willetta (“Billy”) German, died in 1999; he was survived by a daughter Anne and a son Clifford Sewall Webster, Bowdoin Class of 1972.

A sad story: J. Albert Bolton, of Augusta, was born in 1820 and was still alive in 1892. He and his wife Priscilla (Merrill) had only two children. Their daughter “died in infancy” and their son, William A. Bolton, a Cony High School and Boston Commercial College graduate and “a young man of great promise,” died at 21.

J. Albert was the grandson of Savage Bolton, first settler on Augusta’s Bolton Hill. Charles Nash, in his Augusta history, quoted from Martha Ballard’s diary for Oct. 21, 1789: “Savage Bolton and his wife were taken with a warrant for breaking the Sabath.”

* * * * * *

Moving up-river to Sidney, Kingsbury profiled many farmers. Some were descendants of first settlers still occupying family homesteads, others more recent incomers. Quite a few had second occupations. Examples follow.

Frank Abbott, who was born in 1853, was the great-grandson of Joseph Abbott (1743-1833), who in 1804 came from Massachusetts and bought 1,000 acres on the Pond Road. Kingsbury did not specify whether Frank still farmed the original family land.

James H. Bean (1833 -??) combined farming with wagon-making and blacksmithing. He was probably an ancestor of the James H. Bean for whom Sidney’s elementary school, opened Sept. 6, 1957, on Middle Road, is named.

(Sidney historian Alice Hammond wrote that the Bean for whom the school is named was honored for his many contributions to education in Sidney “and is still remembered [in 1992] with love and respect.”)

Civil War veteran Thomas S. Benson moved from Augusta to Sidney in 1876 and was a farmer and deputy sheriff.

Albert Black was the grandson of a former Palermo, Maine, resident who moved to New York State in 1820. Black came back to Maine in 1863, at the age of 23. His agricultural specialty was apples, Kingsbury wrote – he grew them and bought other farmers’ and for 16 years had been making cider vinegar, 10,000 gallons in 1891.

James D. Bragg, a third-generation Sidney farmer born in 1821, and Charles H. Burgess, born in 1861, served as postmasters in two different Sidney post offices beginning in the late 1880s. Hammond wrote that Bragg served for only one month, in 1887. Burgess, whose farm Hammond located on Middle Road, was also a harness maker, Kingsbury said.

Atwood F. Jones, who moved from Mercer to Sidney in 1849 at the age of 27, was a teacher as well as a farmer until 1872, when he became “a dealer in nursery stock.”

Charles H. Lovejoy, the fourth generation of his family in Sidney, “has been messenger in the state senate since 1878.” He had also been a Sidney selectman for 12 years. (Charles’ great-grandfather, Abial Lovejoy [1731-1810], came to Sidney in 1778; see the Feb. 3, 2022, issue of The Town Line for more information on this prominent citizen.)

Stilman S. Reynolds, born in 1818, farmer and mechanic, “has worked on the river twenty years and carried the mail eight years from Sidney to Riverside” (presumably by ferry across the Kennebec).

Oliver C. Robbins (1817-1891) was a butcher and lumberman as well as a farmer. Kingsbury wrote that his widow, Mary (Weeks), and younger son Edwin were continuing the farm after Oliver’s death.

De Merrit L. Sawtelle was the third generation of his family on the same farm, previously owned by his father, Asa, and grandfather, Nathan. His specialty was “breeding and training horses.”

In addition to long family histories in Sidney and multiple occupations, many Sidney farmers had two other things in common. They were Civil War veterans; and, not surprisingly, they tended to marry neighbors and relatives, creating a town full of interrelated families.

For the most part the families were not large. Kingsbury often lists four or five children, but seldom more – with two exceptions your writer thought worthy of note.

Flint Barton (1749-1833; moved to Sidney from Massachusetts in 1773) and his wife Lydia (Crosby) Barton had 12 sons. The 10th, whom they named Anson, was born in 1799; he married Rhoda Sisson and they had 13 more Bartons.

Another man who started a large clan was Thomas Bowman, the second of that name, who moved from Massachusetts to Sidney. Kingsbury did not give dates nor mention Thomas’s wife’s name, but he said Thomas had eight sons, including a third-generation Thomas, and two daughters.

Kingsbury gave brief biographies of five male descendants, all farmers in Sidney. Grandson Isaac had farmed the land formerly his grandfather’s, where “the family burying lot is,” until he died on May 16, 1890, leaving his widow, Phebe (Richards), and oldest son, Isaac N., running the farm.

Correction to August 4 article

Benton historian Barbara Warren wrote to point out an error in the Hinds genealogy in the Aug. 4 piece on natural resources, the section on Augustine Crosby (1838-1898), who invented a gold dredge and married Asher Hinds’ daughter, Susan Ann Hinds (1837-1905).

This writer incorrectly identified Susan Hinds’ father as Asher Crosby Hinds, known as “the Parliamentarian.” Her father was actually Asher Hinds (1792- 1860), whom Warren calls “the builder” (he sponsored the building of the Benton Falls Meeting House in 1828 and in 1830 built the Benton Falls house in which Warren now lives). Warren describes him as “a prosperous farmer and merchant,” War of 1812 veteran and delegate to the Massachusetts General Court.

Susan Ann (Hinds) Crosby was Augustine Crosby’s third cousin and Parliamentarian Asher Crosby Hinds’ aunt. Her brother, another Asher Crosby Hinds, was born in 1840 and died in 1863 in the Civil War. The Parliamentarian’s father was Susan’s brother, Albert Dwelley Hinds (1835-1873).

The confusion is understandable, Warren wrote. For four generations, the Hinds family included an Asher; and Hinds and Crosbys often intermarried.

Update on the Aug. 4 update on the Kennebec Arsenal in Augusta

Kennebec Journal reporter Keith Edwards wrote in the paper’s Aug. 7 edition that Augusta City Councilors voted at their Aug. 4 meeting to declare the historic Arsenal property dangerous. They gave the private owner another 90 days to “address concerns,” and authorized the city codes officer to extend the time to 150 days.

Main sources

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous

Saint Anselm College, in Manchester, New Hampshire, has released the dean’s list of high academic achievers for the second semester of the 2021-2022 school year.

Saint Anselm College, in Manchester, New Hampshire, has released the dean’s list of high academic achievers for the second semester of the 2021-2022 school year.

Endicott College, in Beverly, Massachusetts, the first college in the U.S. to require internships of its students, is pleased to announce its Fall 2021 dean’s list students.

Endicott College, in Beverly, Massachusetts, the first college in the U.S. to require internships of its students, is pleased to announce its Fall 2021 dean’s list students.