Recycled Shakespeare Company to perform ‘The Tempest’

Come away to a private island where the plants, stones, and water are alive. Considered one of Shakespeare’s best fairytales, The Tempest is a magical journey through love, loyalty, and power. Recycled Shakespeare Company, now in it’s sixth season, will be performing at 7 p.m., on Friday, October 18 and Saturday, October 19, at Skills Inc. Ervin Center, 46 Front Street, Waterville.

Come away to a private island where the plants, stones, and water are alive. Considered one of Shakespeare’s best fairytales, The Tempest is a magical journey through love, loyalty, and power. Recycled Shakespeare Company, now in it’s sixth season, will be performing at 7 p.m., on Friday, October 18 and Saturday, October 19, at Skills Inc. Ervin Center, 46 Front Street, Waterville.

With original music and direction by Emily Rowden Fournier, of Fairfield, co-director Helena Page, of Clinton, and stage manager Debra Achorn, of Waterville, the scene comes alive as the exiled Prospero, (Raymond “Wingnut” Wing, of Waterville) creates a magical storm in order to shipwreck the queen and her courtiers. Prospero’s daughter, Miranda (Omm Stilwell, of Vassalboro) does not realize her father’s plan to introduce her to Prince Ferdinand (Cody Curtis, of Bath), but soon learns how she and her father came to be exiled on this island which is inhabited only by them, the monster Caliban (Aaron Blaschke Rowden and Joe Rowden, both of Fairfield) and Ariel, the musical spirit of the island played by nine singers and dancers. With would-be assassins afoot, can Ariel protect the queen and Prospero and still be freed from enslavement? Live accompaniment will be by Fournier on flute and Mia Fairman, of Waterville, on violin.

Recycled Shakespeare Company was founded with the mission of making theater accessible to all while using recycled and repurposed materials. The nonprofit group is Northern New England’s only grassroots Shakespearean community theater and has been featured at the Shakespeare Theater Association’s annual conference in Prague, Czech Republic, for their efforts in creating ecological theater.

This family-friendly production will be presented in the round, with the audience getting a 360 degree view of the stage, and is free to the public. Best view seats can be reserved with a $10 donation. Themed refreshments will be sold.

For more information or to reserve seats call 207-314-8607 or email RecycledShakespeare@gmail.com.

The Kennebec Historical Society is seeking submissions for a logo design for use primarily across digital media.

The Kennebec Historical Society is seeking submissions for a logo design for use primarily across digital media.

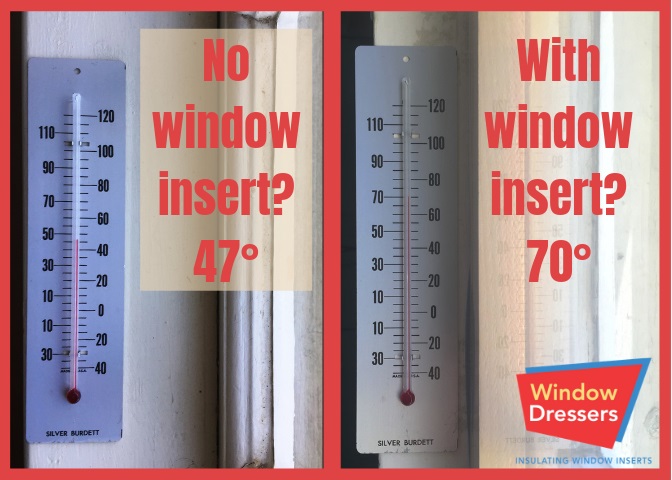

Vassalboro’s F.A.V.O.R. group will be holding a Window Dressers Build from November 16th – 21st. We are looking for volunteers to assist with measuring, frame building and completing the inserts. Now is also the time to request and purchase frames for your winter insulating needs. Please call the Town Office – Debbie 207 872 2826.

Vassalboro’s F.A.V.O.R. group will be holding a Window Dressers Build from November 16th – 21st. We are looking for volunteers to assist with measuring, frame building and completing the inserts. Now is also the time to request and purchase frames for your winter insulating needs. Please call the Town Office – Debbie 207 872 2826.