Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Even more high schools

by Mary Grow

Continuing the discussion of (mostly) 19th-century high school education, this article will talk about Albion, Benton, and Clinton. In following weeks, continuing alphabetically, readers will find information on Fairfield, Palermo, Sidney (don’t expect much), Vassalboro, Windsor and Winslow.

Albion voters first appropriated school money in 1804, and endorsed building schoolhouses the same year. Town historian Ruby Crosby Wiggin said children aged from three through 21 could attend town schools.

Albion began offering education beyond the primary level in the 1860s, according to Wiggin. She referred to “subscription high schools” started in 1860. One was in the “new” (1858) District 3 schoolhouse.

In April 1873, she wrote, interested residents organized a stock company to provide a public hall in an existing building. The leaders quickly sold 90 shares at $10 a share and appointed a three-man building committee.

“It is supposed the building was finished that year [1873] and used for the first free High School,” that started in 1874 or 1875, Wiggin wrote. Henry Kingsbury, in his 1892 Kennebec County history, dated Albion’s “first high school” to 1876.

Because of “lack of interest,” the free high school had closed by 1880. In January 1881 the stock company trustees began the process that led to Albion Grange owning the building (see The Town Line, April 8).

About 1890, Wiggin wrote, high school was reintroduced, this time alternating between the McDonald School (District 9) and the Albion Village School (District 8).

A fall 1891 10-week term in District 8 had 87 students and cost $214; a later 10 weeks at McDonald School with 33 students cost $80. The state paid half the bill, leaving the town to pay $147, Wiggin wrote.

Kingsbury’s information again differs from Wiggin’s. He wrote that the high school started again in 1884 “and has since received cordial support.” He located fall sessions in “No. 10 school house in the Shorey district,” rather than the McDonald School, and spring terms in District 8.

(Both writers could be accurate, if they were describing different years. Also, however, other town historians have disagreed with Kingsbury. Considering that his book ends on page 1,273, and that some of the page numbers double and triple – 480a and 480b come between 480 and 481, for instance – an occasional error seems unsurprising.)

Families again lost interest, Wiggin said, and by 1898 the McDonald School no longer hosted high school classes and the “average attendance at the village was only 18.”

The village school was apparently one built in 1858, after a long debate, on the village Main Street (Route 202) where the Besse Building now stands. It was revived as a high school after 1898, because later Wiggin wrote, “From this school came the first pupil to graduate from Albion High School with a diploma.” His name was Dwight Chalmers, his graduation year 1909.

Wiggin wrote that the old high school building was moved to a new site and in 1964 was a private home.

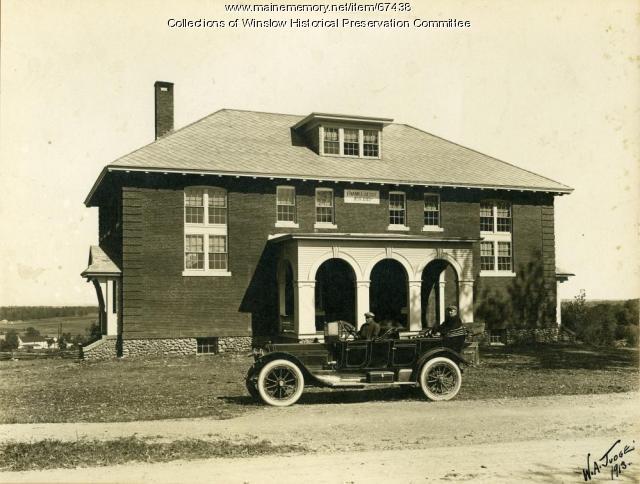

The large brick Besse Building, now home to the Albion town office, was a gift of Albion native and then Clinton resident Frank Leslie Besse. Designed by Miller and Mayo, of Portland, and built by Horace Purington, of Waterville, it was dedicated as Besse High School on Sept. 20, 1913.

Maine School Administrative District (MSAD) #49, now Regional School Unit (RSU) #49, is based in Fairfield and serves Albion, Benton and Clinton. It was organized in 1966. Besse High School closed in 1967 and Albion students began attending Fairfield’s Lawrence High School.

The Town of Benton, northwest of Albion, was part of Clinton until the Maine legislature approved a separation on March 16, 1842. First named Sebasticook, the town became Benton, honoring Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton (1782-1858), on June 19, 1850.

Like other area towns, Benton had multiple villages in the 19th century. Higher education appears to have been concentrated at Benton Falls (sometimes called The Falls).

Benton Falls is on the Sebasticook River just south of the existing bridge, where waterfalls powered manufacturing in the 1800s. The Falls area includes the current locations of the Benton town office, on Clinton Avenue on the west bank, and the Benton Falls Church, on Falls Road on the east bank.

A brief on-line Benton history mentions an “academy” at Benton Falls, along with a church, a library, 10 stores and six taverns, apparently in the first half of the 1800s. Kingsbury adds several mills and in 1824 the town’s only blacksmith shop.

Kingsbury wrote in 1892 that Benton had a high school in the District 5 school building at The Falls, apparently since 1860; and he wrote that Benton’s District 5 schoolhouse was “on the site of the old Clinton Academy.”

But, he wrote, in 1892 there was no local school appropriation, “the proximity of Waterville offering advantages in higher education with which it was useless for Benton to compete.”

(By 1892, Waterville had both a free high school [see the Sept. 9 issue of The Town Line] and Coburn Classical Institute [described in the July 29 issue].)

In Clinton, “the first school in town to teach the higher grades” was what a local group intended as a Female Academy, according to Major General Carleton Edward Fisher’s history of Clinton, or a female seminary, according to Kingsbury.

Fisher wrote that in September 1831 Asher Hinds gave the school trustees an eight-by-nine rod lot on the east side of the road in Benton Falls, and Johnson Lunt added more land. (One rod is 16.5 feet, so the original lot was 132 feet by 148.5 feet.) Kingsbury disagreed slightly, saying construction of the Academy building started in 1830.

The two historians agreed that the would-be founders ran out of resources and handed the incomplete building to the Methodist Society. The Methodist Society finished it and opened a coed high school that ran until around 1858.

After the area separated from Clinton in 1842, Clinton students continued to attend the Academy “for a few years,” Fisher wrote. In 1845, he found, enrollment was 49 male and 31 female students.

The school year then was two 11-week terms, beginning in September and March. Students were charged $3 for the “common branches,” $3.50 for natural sciences and $4 for languages (unspecified).

By 1853, Fisher wrote, there were no students from Clinton enrolled, but the Board of Trustees still had two Clinton members. The school closed in 1858, he said.

Kingsbury recorded that the building changed hands three times in 1858 and 1859 before being sold to School District 5 in July 1859, with the sellers “reserving the right to hold a high school in it for two terms each year.”

This building burned (in 1870, Kingsbury said) and was rebuilt the next year. In 1883 “an attractive hall was finished off in the upper story.” Whether it was still a high school in 1883 Kingsbury did not say.

There was, however, a free high school in Clinton, started in 1874 and still open in 1892. Kingsbury wrote that the initial funding was $500. The “well attended” high school operated two terms a year, spring and fall, moving among the 13 school districts.

This school was superseded early in the 20th century. On-line Facebook pages feature graduates of the 20th-century Clinton High School that opened in 1902 or, according to a Clinton Historical Society on-line source, was approved by voters in 1902, started classes in February 1903 and had its first graduation in 1906.

A current Clinton resident locates the 1902 high school building on the Baker Street lot where the town office now stands.

The Facebook source says the yellow three-story building was 68-by-40-feet; an accompanying photo shows basement windows. The Historical Society writer specified three classrooms each on the first and second floors and one on the third floor.

This writer said the building housed 12 grades until 1960 (another source said until the 1940s), though it was called a high school. The privy was a separate building out back, until Clinton resident Frank L. Besse paid to have “indoor plumbing and central heating” added in 1917. The next year, Besse funded electricity.

In 1922, the on-line writer said, a second-floor classroom for business classes was divided into two, because “the sound of the new typewriters was annoying to the other students.”

Clinton High School, like Besse High School, in Albion, closed after graduation in 1966, when Clinton joined MSAD #49 and students went to Lawrence High School, in Fairfield. The school building on Baker Street housed middle-school classes either for a “couple of years” (Maine Memory Network) or until June 1975 (Clinton Historical Society), when it was no longer needed and was closed.

After a month of vandalism, the second Clinton Historical Society writer reported, the building burned July 25, 1975. The writer quoted a newspaper article mentioning the “suspicious origin” of the fire.

In 2016, alumni placed a memorial stone by the main door to the town office.

The Besse family in Benton and Clinton

1913 photo of Frank Besse seated in a Cadillac convertible, in front of Besse High School.

There are 11 Besses in the index to Ruby Crosby Wiggin’s Albion history (plus three Besseys), and an on-line genealogy of Besses in Albion lists 105 names.

Kingsbury traced the Albion/Clinton family to Jonathan Besse, born in 1775, “the first male child born in Wayne,” Maine. His son, Jonathan Belden Besse (Oct. 15, 1820 – March 5, 1892), became a tanner and married an Albion girl. Wiggin explained how that happened:

Jonathan Belden Besse was a soldier in the 1839 Aroostook War. Typhoid fever delayed his return home, but when he recovered, he headed back to Wayne on foot, “gun over his shoulder.”

He stopped in Albion for a drink from Lewis Hopkins’ well; Hopkins came outside and they talked; Hopkins said he needed help in the tannery. Besse decided to try it. He “went in, hung his gun on the pegs over the door, and went to work.”

Wiggin suggested maybe “Hopkins’ daughter had something to do with his staying.” An online Albion genealogy says Jonathan married Isabelle Hopkins (c. 1833 – Aug. 8, 1870) on July 29, 1852, in Albion. In 1859, he took over the tanning business; in 1890, he moved it to Clinton, “on account of better facilities for transportation.”

Kingsbury lists the Besse tannery as one of the three important industries in Clinton in 1892 (along with the creamery on Weymouth Hill and the shoe factory under construction in Clinton Village, which was expected to provide 100 jobs). The steam-powered tannery “near the railroad station” had 14 workers.

“Russet linings only are manufactured, the weekly production being 1,000 dozen skins,” Kingsbury wrote.

(An on-line leather supplier’s website describes a Russet lining as “a traditional bespoke shoe lining,” also used for “handtooling/carving, falconry and a host of leather goods.” It “is produced on a mellow dressed calf side tanned in vegetable extracts.”)

Jonathan and Isabelle Besse had five sons and two daughters between 1853 and 1868. Frank Leslie (April 15, 1859 – March 26, 1926) was their fourth child and second son. On Sept. 17, 1881, he and Mary Alberta Proctor, of Clinton, were married in Albion. Kingsbury wrote that he became a partner in his father’s business when he was 25 (therefore about 1884), and by 1892 had taken over.

Wiggin, however, wrote that Frank Besse “joined” his father’s business around 1878. She quoted from his speech at the dedication of Besse High School: he said that “when he joined his father in the ‘sheep skin business’ he had a cash capital of just $94.”

After Jonathan died in 1892, Wiggin wrote, Frank bought out Everett and his sister Hannah (Besse) Trask and became sole owner of the Clinton business. In 1906 he joined two Boston merchants to create Besse, Osborn and Ordell, Inc., a company “buying and selling sheepskins” that Wiggin said still existed in 1964.

(On-line sites today identify Besse, Osborn and Odell as a foreign-owned business headquartered in New York City, incorporated Nov. 11, 1910.)

The on-line genealogy lists no children born to Frank and Mary. It says in the 1900 census of Clinton, Frank’s occupation was listed as “tanner sheep skins.” It adds that the tannery “at one time tanned 3,000 skins a day.”

The Maine Memory Network has a September 1913 photo of Frank Besse seated in a Cadillac convertible, a long dark-colored vehicle with running boards and white-wall tires, in front of the Besse building. The caption says he was still running a tannery in Albion at the time.

According to the on-line genealogy, Frank Besse died March 26, 1926, in Ontario, California. Mary died July 10, 1945, probably in Clinton.

Kingsbury mentioned another of Jonathan and Isabelle’s sons, Frank’s younger brother Everett Belden Besse, who in 1892 was living “on the old homestead.” The genealogy says he was born Jan. 23, 1861, in Albion. On Jan. 24, 1889, he married Jessie Ida Rowe, born Nov. 20, 1868, in Palermo; they had four sons and two daughters between 1890 and 1906.

Wiggin wrote that when Jonathan Besse transferred his tanning business to Clinton in 1890, he left Everett in charge of the Albion branch.

In 1905, she continued, the Albion tannery was moved, after town voters offered a tax abatement if it were rebuilt along the line of the new Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington narrow-gauge railroad. Everett Besse ran the tannery at its new location “on the outlet to Lovejoy Pond above Chalmers’ mills” – and on a railroad siding – until it burned down in 1924.

Albion’s first telephone line, in the fall of 1905, was installed by the Half Moon Telephone Company, of Thorndike (then a rival of Unity Telephone Company), to connect Everett Besse’s house to his tannery, Wiggin wrote.

The genealogy says Jessie died May 29, 1940, and Everett died the same year – no month or day is given.

Frank and Mary Besse and Everett and Jessie Besse are among family members buried in at least four Besse plots in Clinton’s Greenlawn Rest Cemetery, on the west side of Route 100 just south of downtown.

Main sources

Fisher, Major General Carleton Edward, History of Clinton Maine (1970).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

COMMUNITY COMMENTARY

COMMUNITY COMMENTARY

Memorial Day Services

Memorial Day Services