Fairfield Sanatorium circa 1940. One of the scourges of the late 19th century through the mid 20th century was Tuberculosis. According to Wikipedia, Tuberculosis (or TB), is an infection caused by bacteria. Typically, it affects the lungs, but can affect other parts of the body. In 90% of cases, the infection remains dormant and goes undetected. In about 10% of cases, the infection goes active. Common symptoms of the active infection include fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Because of the weight loss, the disease was often called “consumption”. Back when it was a major health crisis, those who were infected were often quarantined in sanatoriums. This was common practice across the United States, even here in Maine. The idea was that these sanatoriums would not only separate the sick from the people they could infect, they would also treat the TB. The thought was that they would treat them through good nutrition and fresh air.

Note: “The first article in this Kennebec Valley series appeared in the March 26, 2020, issue of The Town Line. Having completed a three-year run, your writer intends to take a few weeks off.”

Since this historical series started in the spring of 2020 as a way to distract writer and readers from the Covid-19 pandemic, part of the plan has always been a survey of past local disease outbreaks.

Someone at the Maine State Museum had the same idea. The museum has a one-page document uploaded in 2020 and headed Maine’s Historic Pandemics.

(The difference between an epidemic and a pandemic is that an epidemic is localized to a country or region; a pandemic affects multiple countries or the whole world. Since this article is focused on the State of Maine, your writer reserves the right to use “epidemic” even when the disease described sickened people outside Maine.)

The museum website lists five diseases, three too recent to qualify for your writer’s attention in this article:

- Smallpox was at its height from 1600 to 1800; the worst epidemics had a 30 percent death rate; and it was especially severe among Native Americans (who, unlike Europeans, had no previous exposure to give them a chance to develop immunity).

- Cholera was most frequent in Maine between about 1830 and 1850, with seven separate outbreaks, the museum’s chart says. The death rate is put at 50 to 60 percent.

- Tuberculosis became epidemic from 1900 to 1950, with a 25 percent death rate. One of Maine’s three tuberculosis sanatoriums was in Fairfield – see the Sept. 22, 2022, issue of The Town Line.

- Maine’s polio epidemic ran from 1900 to 1960, mainly affecting children. The death rate is listed at 5 to 15 percent; many who survived were paralyzed or lamed for life.

- Influenza is listed as a pandemic in 1918 and 1919, when the disease spread world-wide. The death rate was 2 percent.

Abandoned Fairfield Sanatorium today

Some Maine local historians frequently mentioned epidemics; others ignored them. Diseases most often noted were smallpox, scarlet fever and diphtheria.

In a 1995 paper for Maine History (reprinted on line in the University of Maine’s invaluable Digital Commons series), John D. Blaisdell called smallpox “one of the most frightening of all diseases.” Often fatal, especially to children, the virus left survivors with permanent scars; the Maine State Museum website says it also caused blindness.

A National Park Service (NPS) website discusses the development of inoculation, the practice of deliberately sharing smallpox by transferring pus from an infected person to a healthy one. Doctors discovered that the person being inoculated would usually have a mild case and would seldom develop the disease again.

The website uses colonial Boston as an example. In a 1721 smallpox outbreak, Puritan minister Cotton Mather heard about inoculation from his African slave, Onesimus, and talked Dr. Zabdiel Boylston into trying it.

The website calls this trial inoculation “incredibly controversial.” People got so angry that someone bombed Mather’s house. Many feared the health consequences, and clergymen insisted that smallpox was “God’s punishment for sin” and therefore inoculation “interfered with God’s will.”

Boylston, undeterred, took the experiment seriously and followed up. He found that the 1721 outbreak killed 14 percent of the people who accidentally caught it from others, versus only two percent of those who were deliberately inoculated.

People slowly accepted inoculation, including George Washington, who promoted it regularly during the Revolutionary War to keep his army healthy enough to fight. In 1777, he ordered soldiers inoculated, “the first medical mandate in American history,” the NPS website says.

Inoculation was succeeded by vaccination, a process using a weakened or altered version of the pathogen against which immunity is desired (an on-line site says today the terms inoculation and vaccination are used synonymously). Blaisdell wrote that the earliest smallpox vaccine was developed in Great Britain by Edward Jenner in 1798; the idea came to Boston in 1799 and was “quickly accepted by the American medical community.”

The earliest local reference to smallpox your writer found was in James North’s history of Augusta. He mentioned an October 1792 outbreak among Hallowell residents; “Mr. Sweet and two of his children died with it,” he wrote.

In 1816, Vassalboro historian Alma Pierce Robbins said in her chapter on schools, there was enough fear of a smallpox outbreak that, she quoted (from town records), “a sum was voted to insure the Inhabitants against small pox.”

The earliest disease outbreak Wiggin mentioned in her Albion history was in 1819.

Smallpox was spreading among townspeople, and there was agreement on what to do about it, so voters created a committee to “use every effort to prevent the further spread of small pox.”

Wiggin added that there was no further information on the committee’s success or failure in town records, and neither she nor Robbins gave any hint as to the method(s) used. Wiggin wrote that she found records of another outbreak years later.

Also in 1819, Blaisdell referenced a Penobscot Valley outbreak, starting in Belfast and moving up the river. He said that Hampden doctor Allen Rogers used vaccination as one method of fighting it.

Blaisdell noted another outbreak in early 1840 in Winterport and Bangor.

Linwood Lowden wrote in his history of Windsor that an 1864 town meeting warrant asked for money to compensate Patrick Lynch “for damage received on account of being fenced up [quarantined] for the public safety in the case of small pox.” On May 14, 1864, voters approved paying Lynch’s doctor’s bill.

Lowden found a record of a smallpox vaccination – probably not the first one in town, he wrote – on Thursday, Nov. 12, 1885, when a Dr. Libby, from Pittston, vaccinated Orren Choate.

Another 19th-century method of controlling smallpox, diphtheria and other contagious diseases was fumigating the premises with a gas like chlorine, cyanide or formaldehyde, Lowden wrote.

Cholera, an intestinal disease characterized by severe diarrhea, is caused by a bacterium that is usually transmitted through contaminated water or food. The disease is often fatal unless it is promptly diagnosed and treated.

The major way to prevent cholera is adequate sanitation. It is now uncommon in developed countries, but epidemics still occur in parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America. Cholera vaccines are available and are recommended for residents of and travelers to areas where the disease is common.

Your writer found no records of cholera in the Kennebec Valley, but it could well have killed residents here, because it has been documented elsewhere in Maine. An on-line site, citing an April 2020 article in the Bangor Daily News, mentions outbreaks in Bangor in 1832 and in 1849, and one in Lewiston in 1854 that caused 200 deaths.

The article says the cause of the 1832 Bangor outbreak was a trunk of clothing that had belonged to a sailor who died of cholera in Europe. When his belongings were sent home and shared among family members and friends, the disease was shared, too.

The history article in the Dec. 1, 2022, issue of The Town Line mentioned an 1883 case of scarlet fever in East Machias that was attributed to contaminated clothing brought from an infected area.

Closer to home, Martha Ballard’s diary recorded scarlet fever in Hallowell in the summer of 1787. Entries in June, July and August describe patients with “the rash” or “canker rash” (an old name for “a form of scarlet fever characterized by an ulcerated or putrid sore throat,” according to the 1913 edition of Webster’s Dictionary).

Captain Henry Sewall’s son Billy died June 18, a week after Ballard was first called to see him because he was “sick with the rash.” By the end of July Rev. Isaac Foster had it and was unable to preach. (Last week’s history article summarized relations between Sewall and Foster.)

Early in August, Ballard was back and forth among several households with sick children, some she explicitly said had scarlet fever and others so ill they must have had it too. All the McMaster children caught it, and William McMaster died; Ballard sat up all night with him before his death, and wrote of her sympathy for his pregnant mother.

On Aug. 7, Ballard started at Mrs. Howard’s where her son James was “very low”; went to see Mrs. Williams, who was “very unwell”; to Joseph Foster’s to check on the children there; and to her back field to gather some “cold water root” that she took to Polly Kenyday for a gargle, “which gave her great ease.” When she got home, she found her husband with a very sore throat; he too benefited from the cold water root and “went to bed comfortably.”

The 1899 Windsor Board of Health report, cited in Lowden’s town history, recorded eight scarlet fever cases.

Local historians mentioned two diphtheria epidemics in the second half of the 19th century.

During the 1862-63 school year, according to a town report Wiggin cited, 17 students in Albion schools died of diphtheria – she found no record of infant or adult deaths. (That was a sad winter, she pointed out; it was during the Civil War, from which, according to one report she found, only 55 of the 100 Albion men who enlisted returned.)

The 1988 history of Fairfield mentioned a diphtheria epidemic in 1886.

Lowden listed repeated outbreaks of typhoid fever in Windsor. He wrote that it killed four residents in 1850 and “three young men” in 1877; and the 1899 Board of Health report recorded two more cases.

Biographical sketch of Fairfield’s Dr. Frank J. Robinson

The context for the mention of the Fairfield diphtheria epidemic was a biographical sketch of Dr. Frank J. Robinson (Jan. 23, 1850 – February 1942).

A native of St. Albans (about 30 miles north of Fairfield), Robinson taught school before enrolling in Maine Medical School (later Bowdoin College) in January 1874 and graduating from Long Island College of Medicine in 1875 (the writers of the Fairfield bicentennial history do not explain how he did this; they do say he took numerous post-graduate courses).

Robinson practiced in Fairfield for 65 years, in an office in the Wilson block on Main Street until 1936 and thereafter from his 71 High Street home. The Wilson Block was evidently a medical center; the Dec. 16, 1902, issue of the Fairfield Journal, found on the Fairfield Historical Society’s website, reported that “Dr. Austin Thomas, who has come here from Thomaston, is not as has been reported, associated with Dr. I. P. Tash but has leased the offices in the Wilson block, formerly occupied by Dr. Goodspeed.”

Robinson treated people in Benton, Clinton and as far away as Norridgewock, according to the history.

He was still active at a public commemoration of his 89th birthday, the occasion on which the history says he remembered the diphtheria outbreak that infected 44 Fairfield residents.

The Fairfield historians added that he was again honored on his 92nd birthday, the month before his death, recognized as “one of the oldest practicing physicians in Maine, if not in the country.”

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Lowden, Linwood H. good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

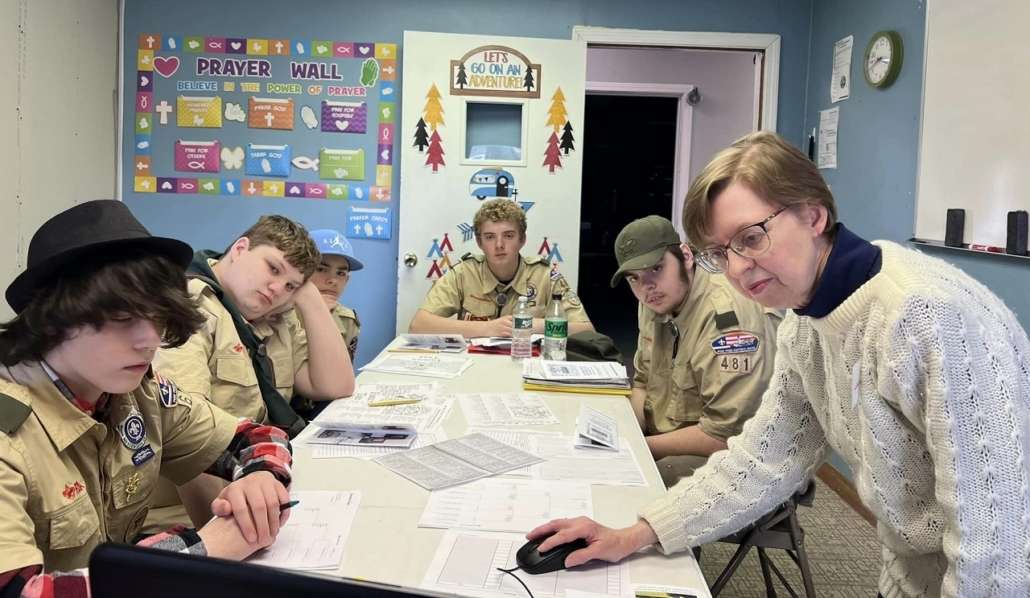

The Kennebec Valley District of Scouting will honor the American Legion, American Legion Auxiliary, and Sons of the American Legion during a special breakfast to be held on Saturday, May 6, at 8:30 a.m., at American Legion Fitzgerald-Cummings Post #2, in Augusta, located at 7 Legion Drive.

The Kennebec Valley District of Scouting will honor the American Legion, American Legion Auxiliary, and Sons of the American Legion during a special breakfast to be held on Saturday, May 6, at 8:30 a.m., at American Legion Fitzgerald-Cummings Post #2, in Augusta, located at 7 Legion Drive.

The following local residents have earned an Award of Excellence at Western Governors University, in Salt Lake City, Utah. The award is given to students who perform at a superior level in their coursework.

The following local residents have earned an Award of Excellence at Western Governors University, in Salt Lake City, Utah. The award is given to students who perform at a superior level in their coursework.