Local scouts attend national event

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Community/by Chuck Mahaleris

Thumbs Up from Anthony and Connor: Anthony Fortin, of Troop #603, and Connor Poirier, of Troop #631, both of Augusta, gave the thumbs up as they began cooking breakfast for the contingent at the sub-camp campsite at the Summit Reserve. (contributed photo)

submitted by Chuck Mahaleris

The Boy Scouts of America Jamboree attracted over 13,000 scouts from around the world and over 5,000 visitors to the 10-day event in July including Scouts from Maine.

Over the course of the Jamboree, which takes place every four years, the BSA gathers together. Scouts and Scouters explored all kinds of adventures – stadium shows, pioneer village, Mount Jack hikes, adventure sports and more – in the heart of one of nature’s greatest playgrounds. With 10,000 acres at the Bechtel Summit Reserve, in West Virginia, to explore, and directly across from the New River Gorge National Park, there was no shortage of opportunities to build Scouting memories.

The 45 scouts and leaders from Pine Tree Council (which covers southern and western parts of Maine) took a bus to the event which was held at the Summit, making stops in Washington, D.C. Contingent Leader, Joan Dollarhite, wrote on July 17, at Camp Snyder outside Washington, D.C., “Tents are pitched, pizza ordered and eaten. We had a great ride and are looking forward to sightseeing tomorrow.” The scouts earned the money for the trip through many fundraisers.

From soaring high above the ground on a zip line to conquering high ropes courses and scaling rock walls, there was no shortage of adventures at the Jamboree. Local Scouts took on the challenge of the climbing wall, navigated their way through orienteering courses, tried new things like branding or welding, and braved the rapids during an exhilarating whitewater rafting trip.

There were also demonstrations from the U.S. Coast Guard and motivational speeches given by Scott Pelley, correspondent for 60 Minutes and former news anchor and managing editor of CBS News who talked about bravery; and Lt. General and Eagle Scout, John Evans, who spoke to scouts about the importance of leadership.

Maine’s scouts not only found their adrenaline rush but also took part in programs designed to foster personal growth and build self-confidence. They also found opportunities to overcome mental and emotional obstacles as well and engage in team-building exercises that required communication, problem-solving, and collaboration. These experiences not only enhance outdoor skills but also cultivate character and resilience. The Jamboree helped to develop leadership skills.

They also took part in a massive good deed. Scouts at the National Jamboree assembled 5,000 “Flood Bucket” cleaning kits consisting of 15 items ranging from rubber gloves and scrub brushes to scouring pads and towels packed tightly into a 5-gallon bucket. These kits serve as essential “first aid” resources that provide flood victims with the practical and emotional support necessary to begin restoration of their homes and personal belongings. The completed kits, valued at $375,000, are being packed tightly into a five-gallon bucket and will be wrapped and transported to a warehouse and then distributed as needed to flooded areas throughout West Virginia as “first aid” resources for flood victims.

Anthony Fortin, of Augusta, attends Cony High School, and is a member of Troop #603. “I earned Radio, Sustainability, and Family Life Merit Badges; did some patch trading; soared across a zip line; had fun at the Camp bashes (parties); attended Catholic Mass with a thousand other Scouts; played the kazoo and the bugle; and met many new people from all over the country,” Anthony said.

Michael Fortin, committee chairman for Troop #603, in Augusta, also attended. “It was fulfilling to see all of the scouts have this amazing experience,” Fortin said. “Many of the scouts on this adventure did not know the leaders and conversely, we did not know most of them. Spending time together provided the leaders with the opportunity to get to know them and witness these young people on their scouting journey. The heat, humidity, and hilly terrain were challenging for us older adults to navigate, but we endured it all to ensure our scouts were safe and had an absolutely awesome time. We saw many examples of scouts who unselfishly embraced the Oath and Law and demonstrated what it truly means to be a Scout.”

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Music in the Kennebec Valley – Part 3

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Central ME, China, Kennebec County, Local History, Oakland, Up and Down the Kennebec Valley, Vassalboro/by Mary Growby Mary Grow

Band music

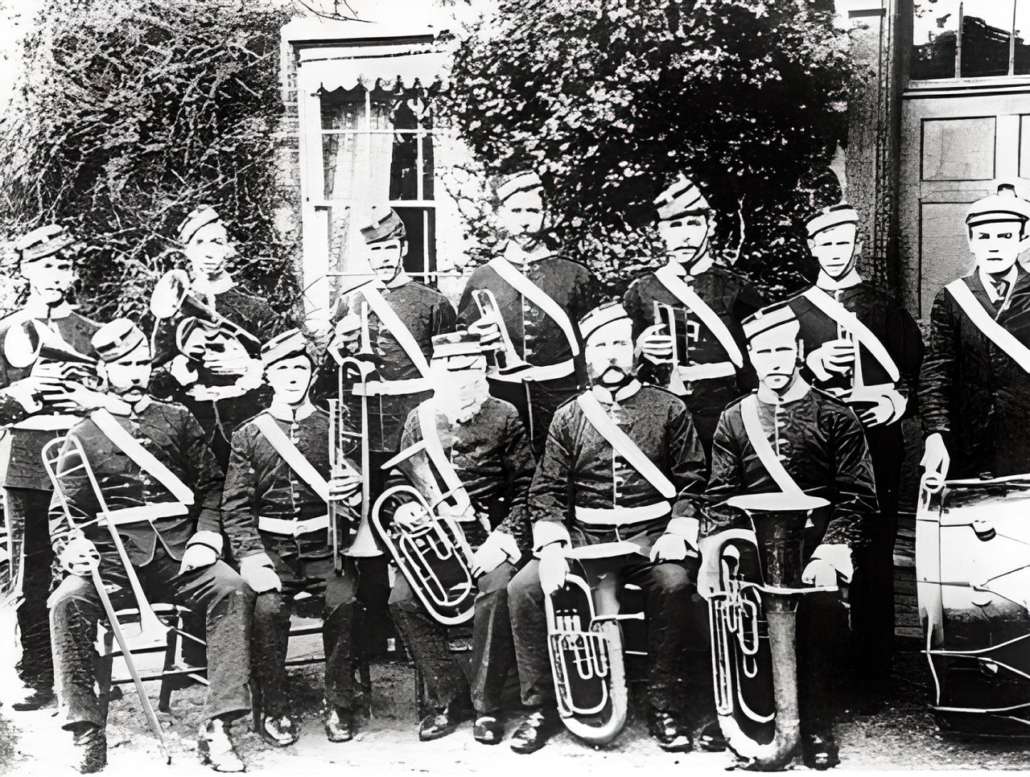

Another type of music in the central Kennebec Valley from early days of European settlement was band music. It was often, but especially in later years not inevitably, associated with military organizations; and like other forms of music, got limited attention in most local histories.

* * * * * *

James North, in his Augusta history, sometimes mentioned parade music, presumably provided by a band, as in his description of former president George Washington’s funeral procession in Augusta on Feb. 22, 1800.

North wrote that the procession was headed by a military escort. It included an infantry company, followed by musicians with “drums muffled, instruments in mourning,” followed by an artillery company.

By 1805, North wrote, Augusta had two military companies, and a group of young men persuaded the legislature (still in 1805 the Massachusetts General Court) to authorize a light infantry company.

The Augusta Light Infantry, which appears frequently in North’s history, was organized in the spring of 1806. North listed its officers and its musicians: fifer Stephen Jewett (the same Stephen Jewett who played the bass viol in church beginning in 1802? – see the July 27 issue of The Town Line) and drummer Lorain Judkins.

Some of the women connected with infantry members created and presented a company standard, with the motto “Victory or Death.” North described the Sept. 11, 1806, presentation as followed by a parade and a ball (presumably at least the ball and probably the parade included musicians).

By the time the Light Infantry was part of the local Federalist party’s July 4 parade in 1810, there was definitely a band. North wrote that its members politely stopped playing as the parade passed the house where Judge Nathan Weston was addressing the rival Democratic party celebration.

Another association between music and the military is the lists of men who fought in the War of 1812. Kennebec County historian Henry Kingsbury and many local historians listed soldiers (in 1812 and later wars) by name and rank, including musicians.

Most 1812 companies had either two or three musicians, though Kingsbury listed only one apiece for two of Vassalboro’s companies. The majority are described unspecifically as “musicians,” but Kingsbury mentioned a drum major and a fife major from Augusta.

By July 4, 1832, North again described two separate parades by two political parties, with multiple bands and military units. The National Republicans’ parade included “the Hallowell Artillery and Sidney Rifles, each with a band of music,” and the Hallowell and Augusta band, which he said was “one of the best in the State.” The Democrats’ parade included some of the Augusta Light Infantry and a band from Waterville.

There was an Augusta band in 1854, when Augusta city officials (the town became a city in 1849) decided the annual July 4 celebration should include recognition of the 100th anniversary of the building of Fort Western. Events included an extremely elaborate parade, with the Augusta Band providing the music.

And on April 18, 1861, as the Civil War began, North wrote that “the Augusta Band, playing patriotic airs” (including Yankee Doodle), led Augusta’s Pacific Fire Engine Company as members marched to the homes of leading citizens to ask their reactions to the rebellion.

(Their visits started with Governor Israel Washburn, Jr., and included his predecessor, former Governor Lot M. Morrill. North commented that Republicans and Democrats alike expressed support for the federal government.)

By August 1863, either there was another band or the Augusta Band had a second name. North described the return of two volunteer regiments whose members’ nine-months enlistments were up.

The 24th Regiment got to Augusta at 10:30 p.m. Aug. 6, by train; a large number of dignitaries and ordinary citizens and the Citizens’ Band escorted the soldiers to the State House for a welcome and a banquet (after which they slept on the State House floor, too exhausted to continue to Camp Keyes). The 28th arrived around noon Aug. 18; their welcoming parade included the Citizens’ Band and the Gardiner Brass Band, and their refreshments were served on the lawn south of the State House.

In 1864, according to North, it was the Augusta Band that on June 3 escorted the first trainload of wounded men to the new military hospital at Camp Keyes, in Augusta.

* * * * * *

In the village of Weeks Mills, in the southern part of the town of China, there was in the latter half of the 19th century an all-male brass band that the China history says “was more a marching band than a dance band,” because its concerts were mostly outdoors.

Sometimes there were concerts in “a town public hall” that was the second floor of a building on the east side of the Sheepscot, north of Main Street (which is called Tyler Road on the contemporary Google map). There was also a bandstand, “with a flagpole,” that band members built at the junction of North Road (now Dirigo Road, perhaps?).

Quoting a former resident named Eleon Shuman, some of whose family were in the band, the history adds, “Few of the band members could read music, and the band director transcribed their pieces into a simpler notation called the tonic sol fa method which they could follow.”

Oakland also had a town band by the late 1880s. In her history of Sidney, Alice Hammond wrote that the organizers of the 1890 Sidney fair spent most of their money to hire the Oakland Band.

She explained that in the absence of television and Walkmans (never mind smartphones), “To hear the band playing as you strolled around the fair grounds, or went into the hall and sat down to take a break was a treat.”

There were also dances some afternoons – “Anyone who wished to dance paid for one dance at a time.” In 1890, the fair was not lighted, so there was no evening music or dancing.

Hammond’s history included reproductions of two posters.

One advertised a Feb. 5, 1892, exhibition of “The marvels of the modern phonograph,” which would “Talk, Laugh, Sing, Whistle, Play on all sorts Instruments including Full Brass Band.” After Professor R. B. Capen, of Augusta, finished his demonstration, there would be a Grand Ball, with music by Dennis’ Orchestra, Augusta, for dancing until 2 a.m.

The second poster announced an Aug. 15, 1898, Grand Concert by the Sidney Minstrels. The program included vocal and instrumental (guitar, banjo and tamborine solos); it was followed by a “social dance” with music by Crowell’s Orchestra.

John Philip Sousa’s inaugural playing of The Stars and Stripes Forever, in Augusta

An on-line site called Military Music says John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever was played for the very first time by Sousa’s Band in the new (opened in 1896) city hall, in Augusta, Maine, on May 1, 1897. Because at that time the march had no title, some historians inaccurately date the first performance to a May 14 concert in Philadelphia.

Contributor Jack Kopstein wrote that Sousa composed the march as he was returning from Europe late in 1896. His original version called for “Piccolo in D-flat, Two Oboes, Two Bassoons, Clarinet in E-flat, Two Clarinets in B-flat (1-2), Alto saxophone, Tenor Saxophone, Baritone Saxophone, Three Cornets (1-3), 4 Horns in E-flat (1-4), Three Trombones (1-3), Euphonium, Tuba, Percussion.”

Augusta’s Museum in the Streets (on line) says by May 1, 1897, Sousa’s Band was “the most famous in the land,” and Sousa was “America’s ‘March King.'” The afternoon concert presented some of his earlier compositions; “Sousa’s band enthralled the Augusta audience with spirited music, and his first encore was a new untitled march” – the one that became The Stars and Stripes Forever.

On-line sites give different versions of the words for the march. The one attributed to Sousa begins, “Let martial note in triumph float / And liberty extend its mighty hand….”

Your writer’s personal favorite begins “Be kind to your web-footed friends / For a duck may be somebody’s mother.” (The web attributes these words to radio comedian Fred Allen [1894-1956].)

Augusta’s 1896 city hall was designed by John Calvin Spofford (Nov. 25, 1854 – Aug. 19, 1936), a Maine-born, Boston-based architect well-known for designing public buildings in New England. In addition to municipal offices, the building included a city auditorium.

Kopstein, writing in 2011, said the building served its municipal function until 1987; it then became an assisted living facility. An on-line description of the Inn at City Hall says it now has “31 apartments with its historic decor preserved throughout the complex.”

Main sources

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984)

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Websites, miscellaneous.

EVENTS – Red Cross: Donation shortfall may impact blood supply

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Community, Events, Gardiner, Waterville, Winslow/by Website Editor The American Red Cross has seen a shortfall of about 25,000 blood donations in the first two months of the summer, which makes it hard to keep hospital shelves stocked with lifesaving blood products. By making an appointment to give blood or platelets in August, donors can keep the national blood supply from falling to shortage levels.

The American Red Cross has seen a shortfall of about 25,000 blood donations in the first two months of the summer, which makes it hard to keep hospital shelves stocked with lifesaving blood products. By making an appointment to give blood or platelets in August, donors can keep the national blood supply from falling to shortage levels.

Right now, the Red Cross especially needs type O negative, type O positive, type B negative and type A negative blood donors as well as platelet donors. For those who don’t know their blood type, making a donation is an easy way to find out this important personal health information. The Red Cross will notify new donors of their blood type soon after they give.

The Red Cross needs donors now. Schedule an appointment to give by downloading the Red Cross Blood Donor App, visiting RedCrossBlood.org or calling 1-800-RED CROSS (1-800-733-2767).

All who come to give throughout the month of August will get a $10 e-gift card to a movie merchant of their choice. Details are available at RedCrossBlood.org/Movie.

Upcoming blood donation opportunities Aug. 16-31:

Augusta: Monday, August 28, 11:30 a.m. – 5 p.m., Augusta Elks, 397 Civic Center Drive, P.O. Box 2206;

Gardiner: Saturday,August 19, 9 a.m. – 2 p.m., Knights of Columbus, 109 Spring Street;

Waterville: Friday,August 18, 9 a.m. – 2 p.m., Best Western Plus Waterville Grand Hotel, 375 Main Street;

Winslow: Wednesday, August 30, noon, – 5 p.m., Winslow VFW, 175 Veterans Drive.

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Music in the central Kennebec Valley

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Central ME, Hallowell, Kennebec County, Local History, Up and Down the Kennebec Valley, Vassalboro/by Mary Growby Mary Grow

After the frustration of finding only scanty and random information from local historians on how central Kennebec Valley residents cared for their destitute neighbors, your writer decided to continue frustrating herself on a more cheerful topic: music.

There were music and musicians in central Maine before the Europeans’ arrival. Music historian George Thornton Edwards provided a bit of information on native American music in his Music and Musicians of Maine.

The early European settlers, too, enjoyed and appreciated music, Edwards wrote. At first it was mostly sacred and mostly vocal.

The usual accompaniment to a church choir was a bass viol. Portland’s Second Parish Church seems to have been a leader in expanding use of instruments. Edwards wrote that the cornet and clarinet (or clarionet) had supplemented the viol before 1798, when the church acquired the first church organ in the city.

Augusta wasn’t far behind. In 1802, according to Edwards and to James North’s Augusta history, residents of the North Parish raised $35 to buy a bass viol and build a box for it. Stephen Jewett played the viol; Edwards commented that “ultra conservative” residents no doubt disapproved.

North included a reference from 1796, when Hallowell Academy, opened May 5, 1795, celebrated the end of its first year with public student recitations. North quoted from the May 10, 1796, issue of the Tocsin (Hallowell’s second newspaper): the public presentation included “vocal and instrumental music, under the direction of Mr. Belcher the ‘Handel‘ of Maine.”

(“Mr. Belcher” was Supply Belcher [March 29, 1751 – June 9, 1836]. Born in Massachusetts, he fought in the Revolution; moved to Hallowell in 1785; and in 1791 settled in Farmington for the rest of his life. He published in 1794 a collection of his sacred compositions called The Harmony of Maine.)

North borrowed from Edwards’ history a description of another series of musical events that started in early 1822, when a group of musically-inclined South Parish Congregational Church parishioners brought to the town “Mr. Holland,” a professor of music from New Bedford, Massachusetts. (Your writer has failed to find Mr. Holland’s first name or dates.)

Holland began a new method of teaching “psalmody” (the singing of sacred music, especially in church services) and gave piano lessons. His singers joined the church choir, and the ensuing interest led to raising money to buy a $550 British-made organ, the first organ in Augusta. It was installed on Sept. 4, North said.

The next Sunday, “Mrs. Ostinelli,” Sophia Henrietta Emma Hewitt Ostinelli (May 23, 1799 – Aug. 31, 1845), played the organ. She was the daughter of Boston composer, conductor and music publisher James Hewitt, and the new wife of Italian-born violinist and conductor Paul Louis Antonio Ostinelli (1795 – 184?). An on-line source calls her “pianist, organist, singer, and music teacher.”

Edwards wrote that her husband was described as a violinist “without a peer in America at that time.” He was also an orchestra conductor.

On Sept. 19 and again on Sept. 25, Holland directed “an oratorio of sacred music,” held, Linda Davenport wrote in her Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier, at the church. The concerts were benefits, the first for Holland and the second for the Ostinellis.

Music was provided by church members – the church did not seem to have its own “ongoing musical society,” Davenport wrote – plus choir members from Hallowell’s Congregational and Baptist societies. At one of these concerts, maybe both, Ostinelli played violin solos.

Davenport reprinted the program of the Sept. 19 concert. Each of the two parts began with an organ voluntary, followed by vocal music, both chorus and solo. Seven of the 15 pieces performed were by George Frideric Handel; one was by Franz Joseph Haydn.

North wrote the Holland concerts were the last time such “first class concerts” were presented in Augusta until June 1859, when Ostinelli’s daughter Elise, Madame Biscaccianti, sang.

Holland moved back to New Bedford in September 1823, Edwards wrote. “It is said that his influence on the musical life in Augusta is felt to this day (1928).”

The same year Cyril Searle was “temporarily located in Augusta and he continued the excellent work which had been started by Mr. Holland.”

North devoted three pages to Searle – not to his musical career, but to a description of the sketch he did of Augusta, probably in 1823 (definitely after Maine and Massachusetts separated in 1820, and before a building he included burned on Nov. 8, 1823).

When Augusta’s first Unitarian church, called Bethlehem Church, was built in 1827, it had an organ, North wrote. This church, according to Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, was on the east bank of the Kennebec, where the Cony Flatiron Building (formerly Cony High School) stands today. Since most of the Augusta Unitarians lived on the west side of the river, a new church was built only six years later on State Street, about a block north of the present Lithgow Library.

In later descriptions of new church buildings, North occasionally mentioned an organ; apparently by the 1830s, they were common enough not to be worth noting.

An event he described that will remind readers of the old saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” and in which music played a minor role, occurred in 1832.

By then Maine’s capital had moved to Augusta. The legislature, meeting in secret session, discussed a controversial proposal to cede land to Great Britain to resolve the conflict over the Maine-Canada boundary (a conflict that led to the Aroostook War of 1839 – see the March 17, 2022, issue of The Town Line).

An anonymous source sent information on the secret deliberations to Luther Severance, publisher of an Augusta newspaper, who printed it. Legislators demanded to know the source. Severance refused to answer committee questions and was threatened with a contempt citation, but was apparently never prosecuted.

Enough of Augusta’s elite sympathized with Severance to organize a dinner in his honor, at which speakers denounced legislators, praised the free press and, North quoted from Severance’s newspaper, enjoyed “an excellent dinner, moistened with the best old Madeira, and accompanied by fine music.”

* * * * * *

There were also privately run singing schools, Edwards wrote. Millard Howard wrote in his Palermo history that schoolhouses were one place singing schools met. He added that by the late 1800s, schoolhouses were also sites for “some rowdy dances with frequent fights.”

Edwards’ history includes names of people, mostly men but some women, who ran singing schools. One was Coker Marble, whose singing school in Vassalboro operated for more than 20 years in the period from 1836 through 1856.

An on-line Marble genealogy provides limited information on not one but two men named Coker Marble. The genealogy starts with Samuel Marble (Oct. 23, 1728 -?) and Sarah Coker (June 21, 1735 -?), who married in 1754 in New Hampshire. They had at least three children: Hannah and John, both born in 1755, and Coker Marble Sr. (Sept. 28, 1765 – Aug. 30, 1823).

Coker Marble Sr., married twice, according to the on-line genealogy. He and his first wife, Polly Mason, whom he married about 1796, had at least one daughter.

On Jan. 1, 1801, in New Hampshire, he married Rhoda Judkins (1776 -1864). The oldest of their six children was Coker Marble Jr. (Feb. 8, 1802 – Sept. 10, 1882), who was born in Vassalboro.

In his chapter on Vassalboro in the Kennebec County history, Kingsbury named Rev. Coker Marble as pastor – presumably the first pastor – of the Second Baptist Church, organized at Cross Hill in 1808 with 37 members but, Kingsbury said, “probably…no church property.” From the dates in the genealogical information, this pastor must have been the senior Coker Marble, who would have been in his mid-40s in 1808.

Grave marker for Elder Coker Marble Sr., left, and his wife, Rhoda, on right., at the Cross Hill Cemetery, in Vassalboro.

Vassalboro cemetery records show that Coker Marble Sr., named as Elder Coker Marble, and Rhoda are buried in Vassalboro’s Cross Hill cemetery, with the two youngest of their four daughters.

(Your writer also found on line a biography of a Massachusetts doctor named John Oliver Marble. The biography specifies that he was the son of John and Emeline [Prescott] Marble and the grandson of Rev. Coker Marble. Dr. Marble was born April 26, 1839, in Vassalboro. He graduated from Colby in 1863 and received his medical degree from Georgetown in 1868.)

Coker Marble Jr., married Marcia Lewis (March 19, 1806 – Dec. 17, 1881) on Aug. 31 or Oct. 20, 1824, in Whitefield. Between 1825 and 1853 Marcia bore seven daughters and three sons. The sons were named Arthur, Edwin and Henry.

From the birth and death dates, your writer concludes that it was Coker Marble Jr., who ran the Vassalboro singing school, probably beginning when he was in his early 30s. The genealogy lists two of his and Marcia’s children as born in Vassalboro, in 1837 and 1841, and two others in Hallowell, in 1839 and 1845.

The on-line site says the younger Coker Marble lived in Pittston in 1870 and Skowhegan in 1880; Marcia is listed in Pittston in 1870 and in Milburn in 1880 (Milburn might then have been part of Skowhegan). Both died in Bath (another site says Coker Marble died in either Bath or China) and are buried in Bath’s Maple Grove Cemetery.

Main sources

Davenport, Linda, Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier Maine’s Sacred Tunebooks, 1800-1830 (1996).

Edwards, George Thornton, Music and musicians of Maine: being a history of the progress of music in the territory which has come to be known as the State of Maine, from 1604 to 1928 (1970 reprint).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W. , The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Scouts leadership group completes training

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Belgrade, Community, Whitefield, Windsor/by Chuck Mahaleris

Adam Wright, of Lewiston, Doug Woodbury, of Rockport, and Jon Martin, of Augusta, demonstrate round lashings. They learned the skill so they can then instruct their Scouts on the skill. (photo courtesy of Chuck Mahaleris)

by Chuck Mahaleris

Leaders from Cub Packs and Scout Troops around the area recently completed a variety of training programs. “It is encouraging to see so many scout leaders coming out to learn new skills,” said Walter Fails, of Farmington, who is the Chairman of Training for Scout Troops in Kennebec Valley District. “Every scout deserves a trained leader because trained leaders deliver better and safer Scouting programs.”

At Camp Bomazeen, in Belgrade, 20 scouting leaders from across Pine Tree Council completed the Basic Adult Leader Outdoor Orientation (BALOO) Training for Cub Scout leaders and the Introduction to Outdoor Leader Skills (IOLS) Training for leaders in Scout Troops. The training courses were held over the weekend of May 5-7. Both programs provide an opportunity for leaders to learn how to offer Scouting’s outdoor programs safely. “We all had a great time sharing experiences and knowledge,” said Scott St. Amand, of Gardiner, who heads up Cub Scout Leader Training for Kennebec Valley District and was one of the trainers for the weekend. “It was great to see the camaraderie, and willingness to jump in and help each other learn new skills.”

Of those completing the leaders program, it included area IOLS Training: Christopher Bishop, of Whitefield, who is a leader in Troop #609 B(Boys), in Windsor, Jon Martin, of Troop #603 B, in Augusta, Stephen Polley, is a leader, in Vassalboro Troop #410, Shawn Hayden, of Skowhegan Troop #485 B.

Those locally completing requirements for the BALOO Training: Frederick Pullen, of Pack #445, in Winslow, and Christopher Santiago, of Pack #410, in Vassalboro. Santiago also recently completed more than 500 hours of online training to complete the District Committee functions. Chris Fox, of Mechnic Falls, is the Abnaki District Training Chairman and helped with the training at Camp Bomazeen.

Shelley Connolly, of Pittsfield, completed Short Term Camp Administrator training with Western Los Angeles County Council on April 29. Shelley is going to be running the Summer Camporee, at Camden Hills State Park, July 30-August 1, and she will be helping set up the schedule, program, etc., for the Scouts BSA Weekend at Bomazeen.

EVENTS: Shakespeare group to hold auditions

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Community, Events/by Website Editor

Front row, from left to right, Katie Howes, Tammy Werber, and Vanessa Glazier. Back, Becca Bradstreet, Shana Page, Josh Fournier, and Helena Page. (photo courtesy of Shana Page)

Recycled Shakespeare Company will be holding auditions for their theatrical production, The Poe Experience.

Auditions are on Monday, July 17, from 6 to 8 p.m., at the Fairfield House of Pizza, in Fairfield, and Wednesday July 19, from 6 to 8 p.m., at the South Parish Congregational Church, in Augusta.

This one night only show will take place on Sunday, October 8, at 7 p.m., at the South Parish Congregational Church, in Augusta. It will consist of a reader theater approach with and pantomime. Please be prepared to do a cold read. There are roles for readers, silent performers, and help with staging, costuming, tech, and more. Everyone who wants a part gets a part and actors are encouraged to help with various aspects of the production.

If you cannot audition during these times, please contact Shana Page at 207-286-5713 or shanalynnpage@gmail.com.

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: The story of Independence Day

/0 Comments/in Augusta, China, Local History, Maine History, Up and Down the Kennebec Valley, Waterville, Windsor/by Mary Grow by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

Local historians make some references to Independence Day celebrations

According to Wikipedia, celebrating Independence Day on July 4 each year is most likely an error.

The writer of the on-line site’s article on this national holiday says that the Second Continental Congress, meeting in a closed session, approved Virginia representative Richard Henry Lee’s resolution declaring the United States independent of Great Britain on July 2, 1776.

Knowing the decision was coming, a five-man committee headed by Thomas Jefferson spent much of June drafting the formal declaration that would justify the dramatic action. After debating and amending the draft, Congress approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 – having approved the act of independence two days earlier.

Wikipedia further says that although some Congressmen later said they signed the declaration on July 4, “[m]ost historians” think the signing was really not until Aug. 2, 1776.

The article includes a quotation from a July 3, 1776, letter from John Adams, of Massachusetts, to his wife, Abigail. Adams wrote that “[t]he second day of July 1776…will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival.”

Adams recommended the day “be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

And so it has been – two days late.

Wikipedia says July 4 celebrations began in 1777, in Philadelphia, where the observance included an “official dinner” for members of the Continental Congress, and in Bristol, Rhode Island. The Massachusetts General Court was the first state legislature to make July 4 a state holiday, in 1781, while Maine was part of Massachusetts.

Windsor historian Linwood Lowden mentioned the importance of the local Liberty Pole as part of Independence Day observances. Liberty Poles, he explained were put up after the Declaration of Independence as symbols of freedom. Many later became town flagpoles; Windsor’s, at South Windsor Corner (the current junction of routes 32 and 17), was still called a Liberty Pole in 1873.

The central Kennebec Valley towns covered in this history series have quite probably celebrated the holiday annually, or almost annually, since each was organized. As with other topics, local historians’ interest, and the amount of available information, vary from town to town.

James North’s history of Augusta is again a valuable resource. He described Independence Day celebrations repeatedly, beginning with 1804 (it was in 1797 that Augusta separated from Hallowell and, after less than four months as Harrington, became Augusta).

In 1804, North describes two celebrations, divided by politics. The Democrats, or Democratic-Republicans (the party of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and others) gathered at the courthouse, where Rev. Thurston Whiting addressed them.

(Whiting is listed in on-line sources as a Congregationalist. He preached in Newcastle, Warren and before 1776 in Winthrop, where he “was invited to settle but declined,” according to a church history excerpted on line. He preached in Hallowell in 1775 [then described as “a young man”], and in 1791 is listed in Hallowell records as solemnizing the marriage of two members of prominent Augusta families, James Howard, Esquire, and Susanna Cony.)

The Federalists (the party of Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and others) began celebrating at dawn with “a discharge of cannon,” North wrote. They organized a parade at the courthouse that went across the Kennebec and back to the meeting house where an aspiring young lawyer, Henry Weld Fuller, gave a speech. The day ended with a banquet at the Kennebec House (a local hotel that often hosted such events), during which participants “drank seventeen regular toasts highly seasoned with federalism.”

(Hon. Henry Weld Fuller [1784-Jan. 29, 1841], born in Connecticut, graduated from Dartmouth in 1801, studied law and came to Augusta in 1803. He married Ester or Esther Gould [1785-1866], on Dec. 21, 1805, or Jan. 7, 1806 [sources differ]. They had seven children, including Henry Weld Fuller II [1810-1889], who in turn fathered Henry Weld Fuller III [1839-1863], who died without issue. North wrote that the senior Fuller served in the Massachusetts legislature in 1812 and 1816 and in the Maine legislature in 1837. He was appointed Kennebec County attorney in 1826 and was a Judge of Probate from 1828 until he died. His grandson, Henry III’s brother Melville Weston Fuller, was Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.)

By the summer of 1807, the Democratic Republicans had elected one of their number, James Sullivan, as governor of Massachusetts, and the Maine party members “were in high spirits,” North wrote. On July 4, they heard an oration by Rev. Joshua Cushman, of Winslow, and partook of a dinner for 150 people in lavishly decorated courthouse.

Cushman’s speech was published; North wrote that “it attacked federalism with more vigor of denunciation than truthfulness or discretion.”

(Wikipedia says Rev. Joshua Cushman [April 11, 1761 – Jan. 27, 1834] was a Revolutionary War veteran who graduated from Harvard in 1787 and became a minister, serving Winslow’s Congregational Church for almost two decades. He was a member of the United States House of Representatives representing Massachusetts from 1819 to 1821, and with Maine statehood continued as a Maine member until 1825. He had just been elected to the Maine House of Representatives when he died. Wikipedia says “He was interred in a tomb on the State grounds in Augusta.”)

By July 4, 1810, the Augusta Light Infantry had been organized and paraded as part of the Federalist celebration, which North believed was held in Hallowell. He listed a parade including the Light Infantry as part of the 1810 and 1812 celebrations as well.

Because 1826 was the 50th anniversary of independence, Augusta officials organized an all-day celebration, North wrote. It began with a “discharge of cannon and ringing of bells” at dawn and continued with a parade, a ceremony, another parade, a dinner and fireworks set off on both sides of the Kennebec.

One of Augusta’s most prominent residents, Hon. Daniel Cony (Aug. 3, 1752 – Jan 21, 1842), presided at the banquet. Attendees included General John Chandler (Feb. 1, 1762 – Sept. 25, 1841), then in his second term as a United States Senator; Peleg Sprague (April 27, 1793 – Oct. 13, 1880), then a member of the United States House of Representatives and later a U.S. Senator; and “some officers of the army and navy who were engaged in the survey of the Kennebec.”

Also present, North wrote, was Hon. Nathan Weston (March 17, 1740 – Nov. 17, 1832), whom Cony introduced as the “venerable gentleman” who served in the Revolutionary army and fought at Saratoga with him. North wrote that Weston “briefly review[ed]…the events which preceded and led to the war of the revolution, noticing the severity of the struggle and the spirit which brought triumphant success, gave the following toast: ‘The spirit of ’76 – alive and unspent after fifty years.'”

(North’s history includes two biographical sections on this Nathan Weston, whom he usually called Capt., and his son, also Nathan Weston, who was a judge and whom North usually called Hon. North did not write anything about Capt. Weston’s military service after the French and Indian wars. However, the younger Nathan Weston was born in 1782 and could not have fought in the Revolution.)

By July 4, 1829, Augusta had been designated Maine’s new state capital (succeeding Portland), and Independence Day was chosen as the day to lay the cornerstone of the State House, leading to “unusual ceremonies and festivity,” North wrote.

The celebration began, as usual, with bells and a 24-gun salute at dawn; continued with a parade featuring the Augusta Light Infantry, many speeches and a banquet; and was climaxed by fireworks set off on both sides of the Kennebec.

One more Independence Day celebration North thought worth describing was the 1832 observance. That year, he wrote, for the first time since 1811, the two political parties – by then the National Republicans and the Democrats – “each had separate processions, addresses and dinners.”

The Democrats got “part of” the Augusta Light Infantry and a band from Waterville for their parade and held their dinner in the State House. The Republicans’ parade incorporated “the Hallowell Artillery and Sidney Rifles, each with a band of music, and the Hallowell and Augusta band.” Their dinner was in the Augusta House.

The local Republican newspaper, identified by North as the Journal, claimed 2,000 people in the Republican parade. The Democratic Age estimated only 700 in the Democrats’ parade, but claimed 1,000 at the State House meal, versus only 400 or 500 at the Republican dinner.

North wrote that the Journal admitted the Democrats fed a larger crowd, but, North quoted, said snidely, “probably half of them dined at free cost.”

Windsor historian Lowden was another who described an occasional Fourth of July celebration, quoting from diaries kept in the 1870s and 1880s by residents Roger Reeves and Orren Choate.

In 1874, Reeves described “Bells, cannon guns, pistols, rockets, bomb shells, fire crackers” on Water Street, but “very little rum” and “no rows.” (Windsor no longer has a Water Street, and your writer failed to find an old map with street names.)

Two years later, Reeves’ family went to the Togus veterans’ home “to see the greased pig caught,” while Reeves himself intended “to celebrate in the hay field.” And in 1878 Reeves again worked all day, earning “a dollar and a pair of slippers” for whitewashing a barn. In the evening he went “up on the hill and played croquet by lamp light.”

Choate went to Weeks Mills for the 1885 Independence Day celebration (he was 17 that year, Lowden said), and wrote that it included races and a dance and he didn’t get home until midnight.

The next year, 1886, July 4 was a Sunday, so the celebration was on Monday. Choate got up at 2 a.m. to join relatives and friends for a trip to Augusta’s celebration, from which they got home at 3 the following morning. “We had a good time,” he wrote, without providing details.

Other local historians made occasional comments about Independence Day celebrations – for example, the Fairfield bicentennial history says that Fairfield’s Civil War monument was dedicated on July 4, 1868.

Your writer hopes that readers remember enjoyable, perhaps moving, ceremonies from years past and will have a safe and fun holiday this year.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: GAR and Togus

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Local History, Maine History/by Mary Grow by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

The Grand Army of the Republic, or GAR, was responsible for more than organizing the local Posts and Memorial Day observances described in previous articles in this series.

Additional information on this Civil War veterans’ organization, from various sources, says it assisted veterans in many ways, including advocating for legislation and policies, providing financial support to needy members and helping them stay in touch with each other.

The organization also “supported charitable causes such as the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Eastern Branch, and the Maine Military and Naval Children’s Home in Bath,” an on-line source says.

In the spring 2004 issue of Prologue magazine, Trevor K. Plante, then an archivist with the National Archives and Records Administration, wrote an article entitled The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

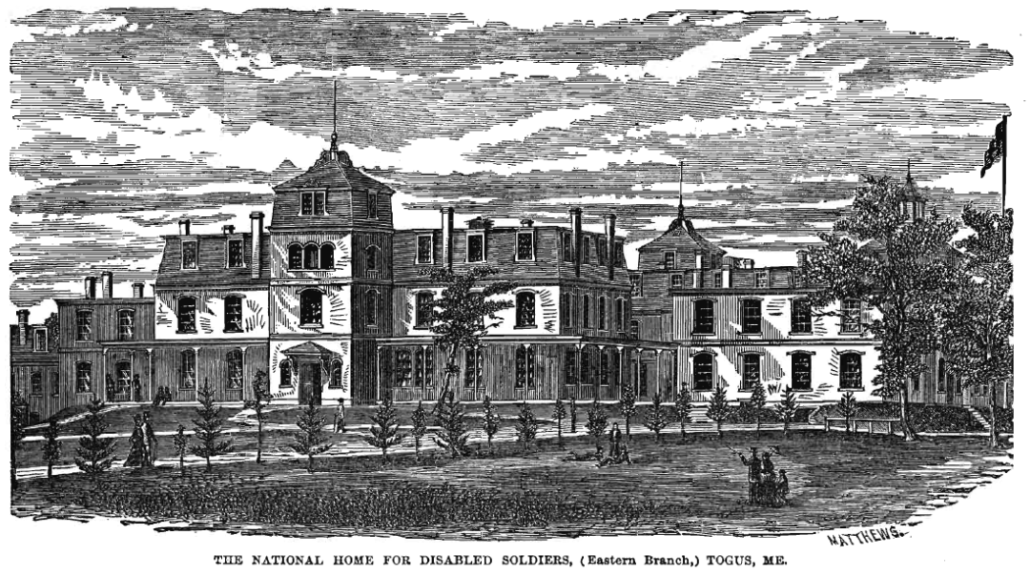

The National Home was actually more than a dozen homes, established by federal legislation in March 1865. The board appointed to carry out the legislation (originally 100 members, reduced to 12 in March 1866) began looking for sites. The first one they approved was an abandoned resort called Togus Springs, in Chelsea, Maine, about four miles southeast of Augusta on the east bank of the Kennebec River.

According to on-line sources (including the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, or VA), “Togus” is a shortened version of an Indian name, Worromontogus, or “mineral water.” The mineral spring, Henry Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history, had been known to white settlers since 1810; it was called the Gunpowder Spring because it reeked of sulfur, and it was supposed to heal “malignant humors.”

In 1859, Horace Beals, described as “a wealthy granite merchant from Rockland, Maine,” bought 1,900 acres in Chelsea, including the spring. He planned to develop a health resort for the rich, a Maine institution that would rival Saratoga Springs, in New York.

In pursuit of his dream, Beals spent more than $250,00 to build “a 134-room hotel, a race course, bowling alleys, bath house, and other recreational facilities,” with a farmhouse and stables.

Kingsbury wrote that the resort opened in June 1859. The Civil War left it struggling; it closed in 1863. Beals went bankrupt and died soon afterwards, and his spa was locally called “Beals’ Folly.”

Beals’ widow sold the property to the Board of Managers for the planned veterans’ homes for $50,000. The managers liked the site for numerous reasons: because of the mineral spring, presumed to be a health benefit; because of the rural setting and isolation from cities, qualities that were supposed to be soothing and to keep veterans away from urban temptations; because the buildings were almost ready for immediate use; and, the VA website says bluntly, “because it was a bargain.”

An on-line source describes Togus and its fellows as “a place for disabled veterans to live if they could not care for themselves or their pensions did not provide enough financial support.”

James North, in his Augusta history, wrote that at Togus, honorably discharged veterans with war-caused disabilities “were fed and clothed, and given religious and secular instruction to fit them for the callings in life to which they may be adapted.”

After some remodeling, the first veteran moved into Togus on Nov. 10, 1866. Wikipedia identifies him as James P. Nickerson, no rank given, of Company A, 19th Massachusetts Volunteers.

There were about 200 ex-soldiers at the facility by the next summer. Another site says most of the men came from three states, Maine, Massachusetts and New York; over half were “foreign born, including a large Irish community.”

To accommodate increasing need, Kingsbury wrote that in 1867 officials added a brick hospital – probably the 50-by-100-foot brick building that North described – and had plans for a chapel and other additions.

The VA site does not mention the January 1868 fire that North described, which destroyed most of the main buildings. (Your writer cited North’s description in the Nov. 10, 2022, issue of The Town Line.) The extensive new construction in the next few years featured buildings specifically adapted to a veterans’ home, and made of bricks (manufactured on the grounds), so they would be more fire-resistant.

North described in detail the four brick buildings that were started in the spring of 1886. They were each 50-by-150-foot, with a basement, two main floors and a mansard roof that provided space for a third floor; they were arranged in a square around a central courtyard.

The first building faced eastward. It had storage space in the basement; a large schoolroom that could double as a chapel, plus a smaller schoolroom and teachers’ accommodations, on the ground floor; and an open second story “to be devoted to such purposes as may be required.”

Two more buildings extended westward from each end of the first building. North wrote that they housed “accommodations for the officers and dormitories for the soldiers, the dining-room, kitchen, post office, telegraph office and reading-room.”

The building that closed the west side of the quadrangle had an ell extending west. Its basement housed “a bath room, laundry, store rooms, bakery, boiler room and wash rooms.”

The first floor was another dining room, with the kitchen in the ell. The hospital occupied the main part of the second floor, with a dispensary and nurses’ quarters.

Other new late-1860s buildings listed on line include “an amusement hall, barn, workshop, and the Governor’s House.”

The Governor’s House was built in 1869. The two-story-and-a-half story, 22-room brick house is still standing; it has been on the National Register of Historic Places since May 30, 1974. It is described as historically significant as “the sole remaining building of the country’s first Veteran’s [sic] Home.”

North wrote that as he completed his history in 1870, a two-story brick amusement hall and another building that would house a 10-horsepower engine and the machine shop, shoe shop and tailor’s shop that it would serve were under construction.

Another major, and very expensive, project, he wrote, was building a reservoir that would cover an acre and would “furnish an unfailing supply of pure water, which is to be taken from Greely pond.”

By 1870, too, the campus was steam-powered throughout, North wrote: “Steam for warming and raising hot and cold water to every part of the buildings, and for cooking and laundry purposes, is generated by two boilers capable of driving a sixty horse-power steam engine.”

Wikipedia’s list of new buildings in or about 1872 reads: “a bakery, a butcher shop, a blacksmith shop, a brickyard, a boot and shoe factory, a carpentry shop, a fire station, a harness shop, a library, a sawmill, a soap works, a store, and an opera house theatre.”

The store, North said, sold desirable items to the residents, with proceeds going into their amusement fund.

In 1872, Wikipedia says, the name was changed: the institution became the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. On Aug. 13, 1873, according to the same source, President Ulysses Grant came to Togus “to review the men who had served with him during the Civil War.”

Wikipedia says in 1878, 933 men lived at Togus, mostly Civil War veterans and a few from the War of 1812 and the Mexican War. Kingsbury added there were 1,400 residents in the spring of 1883 and 2,000 by 1892; by the 1880s, there were 20 additional buildings. The peak population was almost 2,800 in 1904.

The former soldiers lived under military discipline, North wrote. The VA site adds that some of the housing was like barracks, and the men wore “modified army uniforms” (or surplus uniforms, according to Wikipedia).

The men paid for their room and board with their federal pensions, Wikipedia says. Those who were able worked in the shops or the farm. Another source says they were paid “at a rate fixed by the managers,” getting half their pay at intervals and the other half when they left (if they left).

The farm provided much of the residents’ and staff’s food. Writing in 1870, North said “farming operations…are already quite extensive.” There had been 85 head of cattle over the previous winter, he said, “some of which are choice Devon stock.”

Wikipedia says the three dairy Holsteins brought from the Netherlands in 1871 started “the first registered herd of the breed in Maine.”

Togus was connected to the surrounding towns on July 23, 1890, by the narrow-gauge Kennebec Central Railroad that ran to the Kennebec at either Randolph or Gardiner (sources differ). On June 15, 1901, the Augusta and Togus Electric Railway began service.

After that, the VA site says, the veterans’ home “became a popular excursion spot for Sunday picnics. There were band concerts, a zoo, a hotel, and a theater which brought shows directly from Broadway.”

Wikipedia and other sources add baseball games. Wikipedia said the zoo let area residents see “antelope, bear, buffalo, deer, elk, chimpanzees, and pheasants.”

* * * * * *

The Togus grounds include the Togus National Cemetery, which covers 31.2 acres. According to the VA and other sources, this cemetery has two sections, called the West Cemetery and the East Cemetery. The latter opened in 1936 and closed in 1961.

The beginning of the West Cemetery was laid out in 1867, on a hilltop on the west side of the grounds. A VA website says Major Nathan Cutler, of Augusta (see box), was running the institution then and chose the site “because he preferred that attractive hilltop.”

Beginning on April 20, 1867, Cutler oversaw the reburial in the new cemetery of six veterans who had died in the first few months. The website says: “Major Cutler felt the factors of color, rank and religion were of no importance. They were buried side by side since they had been soldiers together.”

In 1889, the then head of the Eastern Branch, General Luther Stephenson, had the cemetery’s Soldiers and Sailors Monument built. It is a stone obelisk, 26 feet high, on a stepped foundation with four dedicatory plaques; the granite was quarried on the Togus grounds.

Residents did the work. One website names two specific contributors: a Pennsylvania marble worker named William Spaulding, who did the design, and a Massachusetts stone-cutter named Jeremiah O’Brien.

By the summer of 2010, the obelisk had so deteriorated that the VA’s National Cemetery Association had to rebuild it. In the process, workers found an 1889 time capsule. An on-line photo of the contents shows a slender bottle; two newspapers, from Augusta and Boston; and a small pipe.

When the restored obelisk was rededicated in September 2010, a new time capsule was added.

Togus had its own GAR post

Togus had its own GAR Post, Cutler No. 48, honoring Major Nathan Cutler, known on the web as “the man who saved the ‘Cutler Bible.'” Here is the story, as told in a 2007 blog by a historian and author named Dale Cox.

In the Civil War battle of Marianna, Florida (Sept. 27, 1864), Cutler was 20 years old; he had abandoned his classes at Harvard and joined the 2nd Maine Cavalry, led at Marianna by Brigadier General Alexander Asboth and after he was wounded by Colonel L. L. Zulavsky.

Cutler led the first Union charge; his troops were driven back by stubborn Confederate soldiers, including some holed up in St. Luke’s Episcopal Church and nearby houses. Zulavsky ordered the buildings burned to dislodge the enemy.

Cutler – or someone else; Cox found the record unclear – refused to burn a church. When the order was repeated, Cutler supposedly “dashed into the burning church and saved the Bible, bringing it through the flames to safety.”

Soon afterwards, “two young members of the Marianna home guard” wounded Cutler badly enough so he was left behind and taken prisoner when the Union forces pulled out the next day.

He survived, however, because Cox recounted later interviews in which Cutler agreed someone, not necessarily himself, had argued for saving the church, and did not claim to have rescued its Bible, perhaps through modesty.

However, in a Sept. 19, 2014, article in the Tallahassee Democrat, in anticipation of the 150th anniversary of the Union raid into Marianna, senior writer Mark Hinson repeated the tale and said:

“It’s a romantic story but it never happened. Cutler was badly wounded before the kerosene torches ever touched St. Luke’s. The Bible was saved by someone else because it was returned to the sanctuary of the new St. Luke’s, where it remains on display to this day.”

Main sources:

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Annual law enforcement service honored 88 fallen Maine officers

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Events/by Mark Huard

Law enforcement officials from around the state marched to the memorial on State St., in Augusta. (photo by Mark Huard, Central Maine Photography)

by Mark Huard

Kennebec County Sheriff Ken Mason salutes the fallen officers. (photo by Mark Huard, Central Maine Photography)

On Tuesday, May 16, 2023 the Maine Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Service took place on State Street, in Augusta, just outside of the states capitol building.

The street in front of the memorial was shut down for the ceremony as columns of officers from various agencies around the state marched from Capitol Park, then stood in formation facing the memorial.

Several speakers acknowledged the fact that this year, no new names were added to the memorial which currently holds the names of 88 members of law enforcement that have lost their lives protecting others. The names of all 88 Maine’s fallen officers were read. A wreath was placed on the memorial as bagpipes played Amazing Grace, and the bugle played Taps.

“Young and old, veteran and rookie. These men sacrificed their own lives to protect life and property in the state of Maine,” said Gov. Janet Mills, during the annual Maine Law enforcement Officers Memorial.