Up and down the Kennebec River: Water power and industry on the river

by Mary Grow

Another use for the Kennebec, and for its tributary streams, was to provide water and water power for a variety of mills and other industries, beginning in the 1790s and continuing well into the 20th century. Kingsbury, in his History of Kennebec County, says sawmills came first, with lumber used locally and exported down the river.

Tanneries were next, because they needed water plus hemlock bark, and hemlocks commonly grew along rivers. The tanning process involved preparing animal hides and soaking them in tannic acid derived from tree bark to make leather. Hemlock bark was preferred, according to a web article, because it has a high tannin content.

Bark was dried, shredded and soaked to get the tannin out. Hides went into the tannin-rich water; redried bark become fuel or, Kingsbury says, was exported.

In Augusta, the dam that provided power for a number of industries was finished in September 1837, though the lock that allowed shipping to go around it took another year. The dam was built and owned by the Kennebec Locks and Canals Company, successor to the 1834 Kennebec Dam Company. Parts of it washed out in spring floods and had to be rebuilt in 1839-1841, 1846, 1850 and 1870.

Kingsbury has a long list of industries started because the dam provided water power: in 1842 a double sawmill and a machine shop, followed by more sawmills, a cotton factory, a flour mill, another machine shop and a kyanizing shop. (Kyanizing is the process of soaking wood in mercuric chloride to prevent decay. It is named after John Howard Kyan, who patented it in 1833 in England.)

Later businesses on the dam produced wooden doors and the wooden parts of windows, broom handles, shovels, pulp and by the 1890s paper. In the 1860s and 1870s, Kingsbury says, Ira Daggett Sturgis (Nov. 20, 1814 – Dec. 28, 1891)) and associates owned two steam mills and a water mill on the dam’s east end, plus timber land, creating “the largest lumbering enterprise ever conducted on the Kennebec river.”

(Sturgis, who will reappear in this series, married Rebecca Russell Goodenow [1815-1894] on Oct. 3, 1836. She is memorialized in one of the nine Tiffany windows in Augusta’s South Parish Congregational Church, built in 1865. Web information suggests the window was provided by their daughter, Sarah Elizabeth Sturgis Haynes, and probably installed between 1895 and 1910.)

The dam as rebuilt in 1870 stood until it was removed on July 1, 1999. The Edwards Manufacturing Company acquired it in 1882 (hence the 20th-century name Edwards Dam). Hundreds of employees produced textiles at machines powered by water wheels until electricity was introduced in 1913. Textile production ended in the early 1980s; after 1984, the dam generated electricity.

In Vassalboro, much of the bank of the Kennebec slopes steeply to the river, limiting riverside development, although various industries grew along tributaries. For example, Ira Sturgis rebuilt earlier sawmills on Seven-Mile Brook and used the lumber in his factory, which was also on the stream. Other water-powered industries were sited along the banks almost to Webber Pond. Kingsbury says Sturgis’s factory produced doors, windows and boxes, including the first orange and lemon boxes exported from Maine.

In the 1860s, Kingsbury says, John D. Lang had a steam-powered sawmill, previously water-powered, on the Lang farm (later owned by well-known Hereford breeder Hall C. Burleigh). The farm is on the section of old Route 202 named Dunham Road.

Farther north, Getchell’s Corner was a significant village in the 1800s, with a post office, a hotel and various industries. Kingsbury mentions an early sawmill owned by John Getchell, succeeded by a tannery owned by Prince Hopkins and Jacob Southwick that operated between 1816 and 1865, on a brook near the Kennebec.

Sidney, on the east bank of the Kennebec, across from and originally part of Vassalboro, had its share of sawmills, gristmills, tanneries and other water-powered industries in the late 18th and first half of the 19th centuries, but Kingsbury lists them all on brooks, none on the Kennebec itself. Alice Hammond, in her History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992, surmises that the river was too powerful to be controlled for use by early mills.

Waterville and Winslow were one town until Waterville was separated in 1802. The earliest mills in Waterville were built along Messalonskee Stream, because its flow was easier to control than the Kennebec’s.

Kingsbury has a long list of dams and manufactories on the stream, including sawmills and gristmills, a carding and clothing mill that became a shingle mill around 1832, an iron company (plows, later stoves), a paper mill, multiple wood-based businesses including a factory that made wooden shanks for shoes, a match factory(1858-1890), a carpet factory, woolen mills and a tannery.

On the Kennebec, Nehemiah Getchell and his son-in-law Asa Redington from Vassalboro built the first dam, from the west shore to Rock Island, in 1792. The site is south of the present downtown and the highway bridge to Winslow. Kingsbury says water-powered sawmills, gristmills and other businesses made that area Waterville’s business center until well into the 20th century.

One of the mills described in both Kingsbury and the Centennial History of Waterville was built in the 1940s by William and Daniel Moor, the same Moors who built ships in Waterville (see The Town Line, April 30). Four stories high, the building housed sawmills, a shovel factory, a plaster mill, a feed mill and storage areas. The July 15, 1849, fire destroyed the entire complex. The Moors rebuilt, and were burned out again in another major fire in 1859.

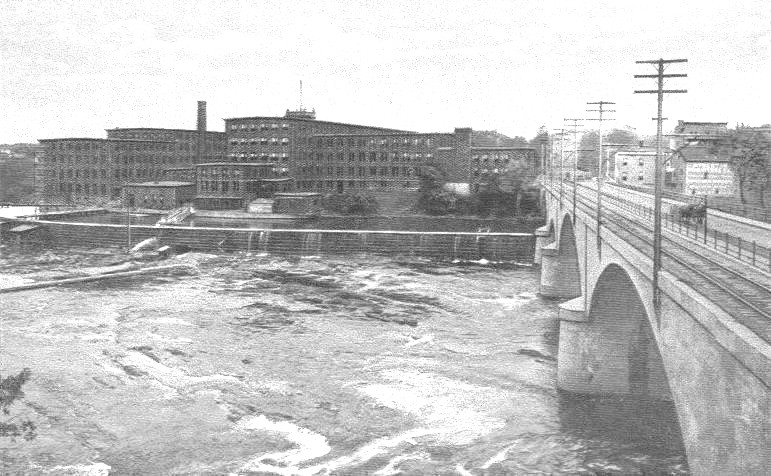

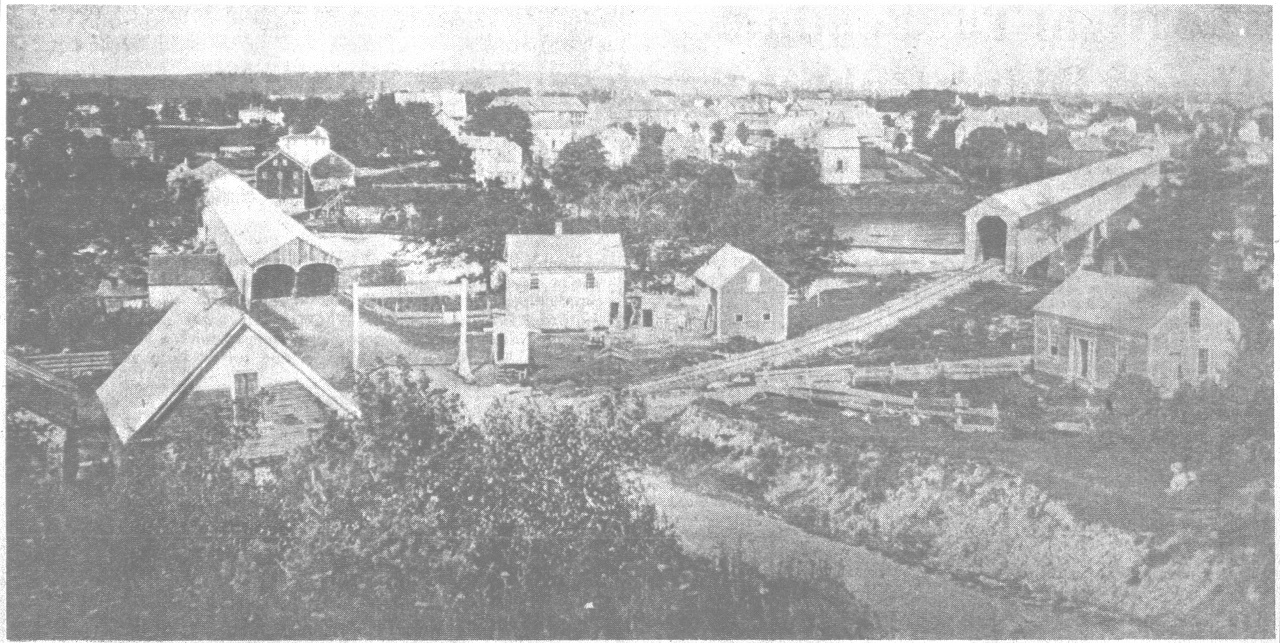

The Lockwood-Duchess Textile Complex on the west bank of the Kennebec River between Waterville and Winslow. Note the horse and buggy crossing the bridge at right.

The Ticonic Water Power and Manufacturing Company was formed in February 1866 and in 1868 invested $40,000 to build a second dam at Ticonic rapids, north of the earlier dam. The company started what became the Lockwood Company, named after industrial designer Amos D. Lockwood (1811-1884). The first brick cotton mill was built in 1873; second and third buildings were constructed in 1882 and 1883. Plocher’s history says by 1900 the Lockwood mill had 1,300 employees.

Cotton textiles were produced until 1956, and from 1957 to 1992 the Hathaway Shirt Factory used one building. The mill complex was added to the National Register of Historic Places in May 2007.

A June 19, 2019, Bangor Daily News article said North River Company, which already owned the Hathaway Creative Center building, bought the other two buildings and plans to begin work on them in the fall of 2020. The goal is to contribute to Waterville’s downtown revitalization plan that includes riverside development.

In Winslow, too, early waterpower came from streams rather than the Kennebec, and manufacturing was scattered through the town. The first major Kennebec River project was the Hollingsworth and Whitney paper mill, started in 1892. Wikipedia says around 1900 the mill was producing 235 tons of paper daily, and was so profitable that the owners provided employees with a clubhouse that had a swimming pool, bowling alley, library and pool tables.

The Hollingsworth & Whitney paper mill on the east bank of the Kennebec River, in Winslow, circa 1905.

Enough employees lived in Waterville that Wikipedia says Waterville’s Two-Cent Bridge was built in 1901 to give them a shortcut to work.

Scott Paper Company acquired Hollingsworth and Whitney in the 1950s and in turn sold to Kimberly-Clark in 1994, Wikipedia says. The mills closed in 1997.

Keyes Fibre, now a division of Huhtamaki Corporation, was started by Martin Keyes, a New Hampshire native who invented plates made of molded pulp. He opened his first small mill in rented space in a Shawmut pulp mill in 1902 or 1904 (on-line sources disagree). After a brief closure in 1905, because the plates were too expensive to be competitive, Keyes improved the process and by 1908 had opened a larger Waterville mill and expanded the product line.

In 1920, to cope with a shortage of pulp, Dr. George Averill, Keyes’ son-in-law and successor as head of the company, opened the company’s pulp mill at the Shawmut mill. Since then the company has changed hands several times and has become an international corporation. The local mill on College Avenue straddles the Waterville-Fairfield line.

Jonas Dutton built the first Kennebec dam in Fairfield, running from the west shore to the western (now Mill) island. The dam supported water-powered sawmills and gristmills owned initially by William Kendall – hence the early (until 1872) name for downtown Fairfield, Kendall’s Mills.

In 1835 and 1836 the Fairfield Land and Mill Association dredged the channel and built a higher dam and new buildings. Soon afterward the river washed away the dam. The Fairfield bicentennial history says the association built a new dam downstream, approximately behind the present post office, which was “unique in having a hinged bulkhead at its downstream end that swung open to release the pressure when the flow of water became excessive at flood stage.”

By the 1850s, the bicentennial history says, the west bank of the Kennebec was lined by a 360-foot series of mills under a single roof. When a fire started in a pail mill near the dam, it took out everything upstream. The owners rebuilt. On a windy day in July 1882 another fire destroyed the mill buildings and threatened the entire village. Another rebuilding followed, and on Aug. 21, 1895, there was a third major fire, described in dramatic detail in the bicentennial history, from which Fairfield’s lumber industry did not recover.

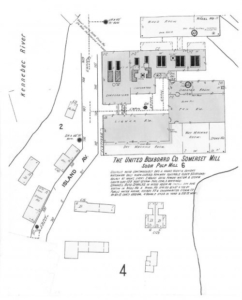

A third dam (perhaps built in the 1850s) connected the north end of Mill Island to the east shore of the river. The island, which is now partly residential and partly a town-owned park, housed industries that included a matchbox factory, a sawmill and a pulp mill. United Boxboard and Paper Company had a three-story brick mill complex at the north end of the island, established in 1882 and running into the early 1930s; remains of the foundation are still visible. At full production the mill employed 100 people; its pulp was used by the company’s other paper mill at Benton Falls and at Hollingsworth and Whitney, in Winslow.

North of what is now downtown Fairfield, Shawmut was a mill village from 1835 until early in the 20th century, primarily producing wood products. The bicentennial history says the Kennebec was dammed there before the 1880s. The village was called successively Philbrook Mills, Lyons Mills (Alpheus Lyon, a Waterville lawyer, built Fairfield’s first flour mill) and Somerset Mills. In December 1904 the Shawmut Manufacturing Company bought the buildings and water rights and the village took the company’s name.

Benton and Clinton, on the east side of the Kennebec opposite Fairfield, also had numerous water-powered industries throughout the 19th century, but they were built on the Sebasticook River and its tributaries. Kingsbury also describes mills near the outlet of Carrabassett Stream, which flows through Clinton into the Kennebec at Pishon’s Ferry opposite Hinckley; but he lists no significant industries along the Kennebec.

Next week: Lumber and ice from the Kennebec

Main sources:

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988)

Federal Writers Project Maine: a Guide Down East (1937)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007 A Short History of Waterville, Maine Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Robbins, Alma Pierce History of Vassalborough Maine 1771-1971 (1971)

Websites, miscellaneous

by Melissa Martin

by Melissa Martin