Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Agriculture – Part 2

by Mary Grow

The Vaughans

Last week’s essay was about early farming in the central Kennebec Valley, as reported in local histories, with emphasis on Samuel Boardman’s chapter on agriculture in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history. This week’s work describes one important farming family and detours to talk about Boardman and another historian who contributed to Kingsbury’s opus.

Boardman wrote that as more people moved into the area and economies diversified, many farms became specialized. Farmers found resources and time to develop specific kinds of crops and of farm animals.

By 1892, when the Kennebec County history was published, Boardman could write about orchardists, dairymen, hay farmers and those who “breed a particular kind of cattle, or fine colts of a fashionable family.” Others specialized in raising what he called “truck crops” to sell to urbanites.

“The orchard farmer lets another make his butter, and the dairyman purchases his apples and often his hay of his neighbor,” Boardman wrote.

Specialization was profitable. Boardman wrote that a farmer in 1892 could earn more cash for “a few acres of early potatoes” sold in town on July 1 than from “the marketed crops of his entire farm” two decades earlier.

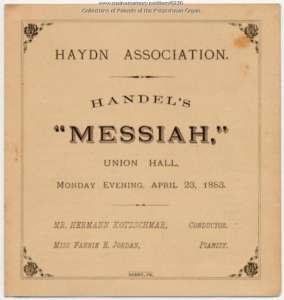

The first two names on Boardman’s list of leaders among the men “to whom the agriculture of Kennebec county owes so much for its early improvement” are Benjamin Vaughan (Apr. 19, 1751 – Dec 8, 1835) and his brother Charles Vaughan (June 30, 1759 – May 15, 1839), of Hallowell. (The Vaughn brothers were featured, with their brother-in-law John Merrick, as patrons of music in the Aug. 31 issue of The Town Line.)

Boardman wrote that the brothers’ inherited land in Hallowell ran for a mile along the Kennebec and extended west five miles to Cobbosseecontee Lake.

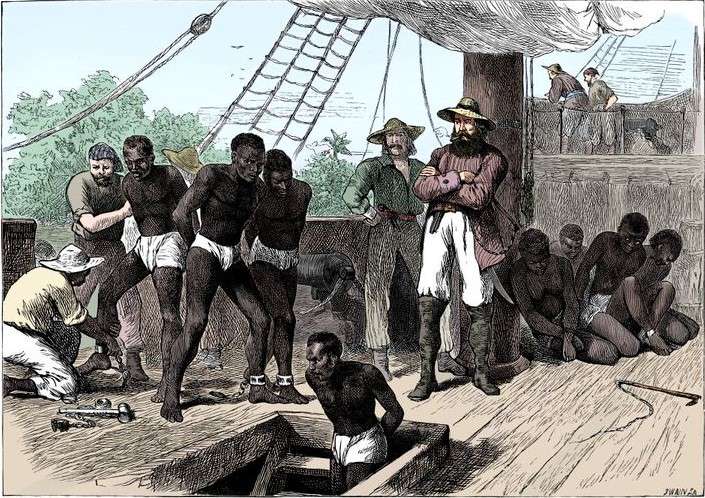

He continued: “They had extensive gardens, established nurseries, planted orchards, imported stock, seeds, plants, cuttings and implements from England, and carried on model farming on a large scale.” (Some of the imported stock was “selected by a skillful English farmer from the herds of England,” James W. North added in his Augusta history.)

They built “miles” of walls on the farms, and built public roads. They sold trees and plants they raised (sometimes as much as $1,000 worth a year); “they also freely gave to all who were unable to buy.” They shared information and their “stock, plants and seeds” with farmers in other towns.

The Vaughans raised “apples, pears, peaches, cherries, and many kinds of nut-bearing trees.” They brought a mechanic from England to set up “the largest and most perfect cider mill and press in New England.”

Charles was more the hands-on manager, Boardman and North agreed, while Benjamin pursued “studies and investigations” (Boardman). Charles’ responsibilities included making sure each “breed of stock or variety of fruit, vegetable or seed” was “carefully tested and found to be valuable and well adjusted to this country” before it was shared. The farms provided year-round employment for “a large number of workmen.”

Benjamin, Boardman wrote, was active in the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture, founded in 1792. Many of his articles were published in the society’s reports, usually signed “A Kennebec Farmer.”

North included background information on Charles Vaughan, writing that he was heavily involved in business development in Hallowell and farther south on the Kennebec in the 1790s. By 1802, he was bankrupt, whereupon he devoted his attention to the family farmland “with his wanted vigor and activity.”

Here are North’s summaries:

Benjamin Vaughan “was benevolent and kind; and was greatly beloved and respected by all classes of citizens for his great usefulness, exalted worth and many virtues.”

Of Charles Vaughan, North wrote: “It was his greatest pleasure to do good, and never was he more happy than when he conferred happiness upon others.”

* * * * * *

While this series of articles has detoured south to Hallowell, from which Augusta separated in 1797, it seems appropriate to mention one more contribution the Vaughan family made to that town (now a city).

According to the chapter on Hallowell by Dr. William B. Lapham, in Kingsbury’s history, the first library in Hallowell was organized Feb. 5, 1842, with a total of 519 volumes. In 1859, the library received donations from John Merrick’s heirs and from George Merrick’s library (George was one of John and Rebecca [Vaughan] Merrick’s sons).

About the same time, Lapham wrote, Charles Vaughan (the first Hallowell Charles Vaughan named his second son Charles) gave the library “a brick store.” The tenants’ rent was to be spent to buy books, and when the store was sold, the money was to be used to create a permanent fund to support the library.

Lapham continued the story after the Merrick/Vaughan involvement: a new granite library building was dedicated March 9, 1880, and by 1892 the collection was almost 6,000 volumes, “many of them rare and valuable.”

Hallowell’s library is now the Hubbard Free Library. Its website calls the 1880 building “the oldest library building in Maine built for that purpose,” and says architect Alexander C. Currier designed it “to resemble an English country church.” The building has been on the National Register of Historic Places since Oct. 28, 1970.

Vaughan Woods in Hallowell

Vaughan Woods and Historic Homestead, in the southern part of Hallowell, preserves the Vaughan family house and some of the family land. Bounded on the north by Litchfield Road and the south by Maple Street, the property combines a house/museum, listed on the National Register of Historic Places since Oct. 6, 1970, and a nature preserve protected by the Kennebec Land Trust.

The main part of the large two-story white house, with its generous windows and broad, tall brick chimneys, dates from 1794, when, Wikipedia says, Charles Vaughan built it as a summer home. In 1797, Benjamin Vaughan made it year-round.

By the late 1800s, the article continues, much of the Vaughan property had been sold off and cleared. In 1890, William and Benjamin Vaughan started buying back and reforesting the land. The present area is almost 200 acres, with Vaughan Brook (also called Bombahook Brook) winding through them from Cascade Pond to the Kennebec.

Information on programs and public access is on line.

Contributors to Kingsbury’s history

More than a dozen of the 47 chapters in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history were written by people other than Kingsbury. The authors include Samuel L. Boardman, who wrote the chapter on agriculture, and Dr. William Berry Lapham, who wrote the history of Hallowell.

Boardman had apparently published his own Kennebec County history years earlier and had been involved with at least two local agricultural newspapers.

In the chapter on the newspaper press in Kingsbury (written by Howard Owen), Boardman is named as agricultural editor of The Maine Farmer, founded in January 1833, for 10 years, from March 1869 to March 1879. Owen added that as of 1892, Boardman was “now employed on the editorial force of the Kennebec Journal.

In Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore’s history of Waterville, S. L. Boardman is mentioned twice: as the author, in 1867, of a history of Kennebec County; and 20 years later as editor of an agricultural newspaper called The Eastern Farmer.

Henry C. Prince, author of Whittemore’s chapter on the Waterville press, wrote that The Eastern Farmer began life in Augusta and in 1887 moved to Waterville under the auspices of Charles O. and Daniel F. Wing, of Waterville, and Hall Burleigh, of Vassalboro. “The paper lost money steadily,” Prince wrote, and after 30 issues the owners sold its subscription list in April 1888 to The Lewiston Journal.

The on-line text of The Maine Genealogist and Biographer lists Boardman as a member of the standing committee of the Maine Genealogical and Biographical Society in 1875 and 1876.

Lapham (Aug. 27, 1828 – Feb. 22, 1894), who authored Kingsbury’s chapter on Hallowell, is described in an article provided by the Bethel Historical Society to the on-line Maine Memory Network as “[o]ne of Maine’s most prolific 19th century historians.”

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.