Asa Bates Memorial Chapel

The Asa Bates Memorial Chapel, also called the Ten Lots Chapel, in the southwestern part of Fairfield, was built between 1916 and 1918 and added to the National Register of Historic Places on Oct. 31, 2002.

PART ONE: TEN LOTS

Ten Lots is the name given to an area in northern Oakland and southwestern Fairfield that was settled in 1774 by families from Massachusetts, including Sturtevants (spelled Sturdifent in the 1790 federal census, according to Jack Davidson’s 2007 history of the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel) and Bateses.

An on-line Oakland history says Quaker Elihu Bowerman, one of the first settlers in North Fairfield (see The Town Line, April 16, 2020, p. 11), was “agent” for the Ten Lots settlers. The New Plymouth Colony had granted 8,000 acres that Bowerman “surveyed, charted and explored” for them. Later, the history says, the grant was expanded by 2,000 acres simultaneously with the arrival of another 10 families who each got a 200-acre lot – thus the name.

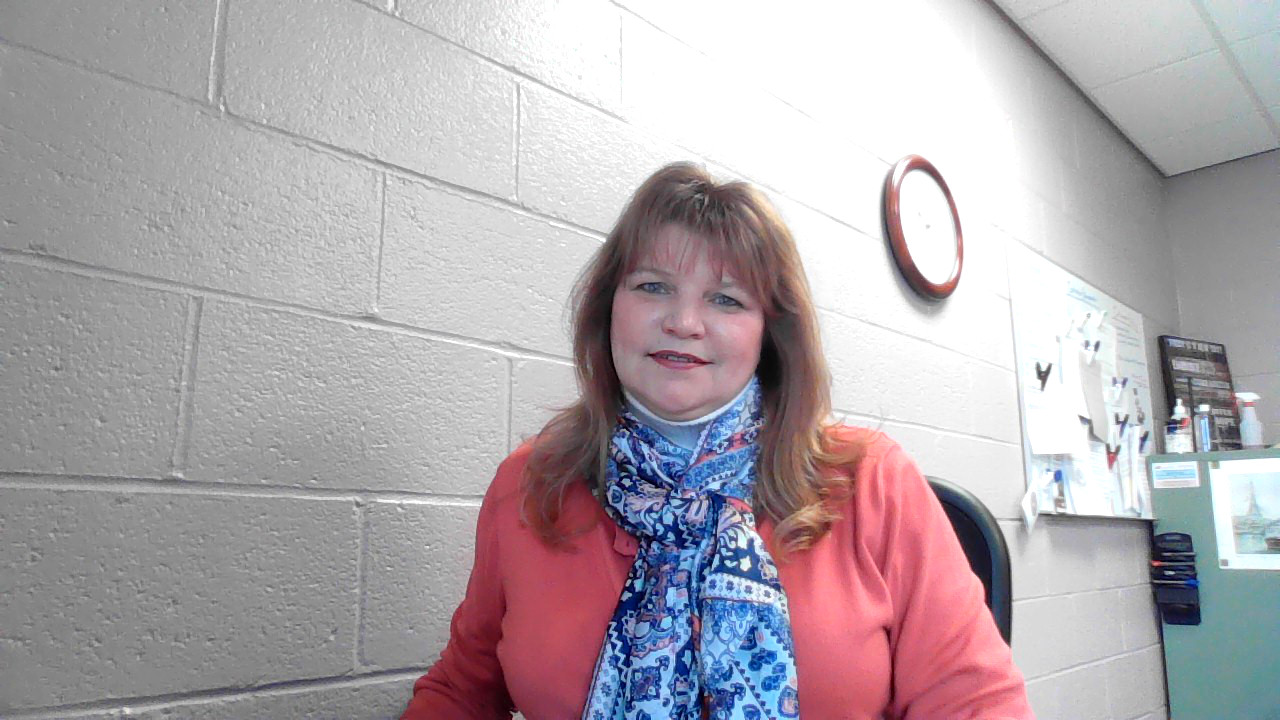

Kay Marsh, a trustee of the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel and unofficial historian, has a map superimposing the boundaries of the ten lots on an area map. The long, narrow lots run from north-northwest to south-southeast, with number one on the north and number ten on the south.

The Ten Lots area was initially part of Winslow. Waterville separated from Winslow in 1802; Oakland, originally West Waterville, separated from Waterville in 1873.

Waterville and Oakland are in Kennebec County. Fairfield, incorporated on June 17, 1788, is in Somerset County. The present dividing line between Fairfield on the north and Oakland on the south, and their respective counties, runs through lot number five of Ten Lots.

Early settlers included Revolutionary War veteran Lot Sturtevant; his descendants included two Reward Sturtevants. The first Bates family members also arrived early in the area’s history; they included Thomas, Samuel and Seth, and there were at least three Bates named Asa. The families intermarried, and both names remained common in Ten Lots for generations.

Despite the Bowerman connection, which has misled some historians, the early Ten Lots families were not Quakers, but Baptists. Ernest Cummings Marriner wrote in his history of Waterville’s Colby College that the first college president, Baptist Jeremiah Chaplin (who served from 1818 to 1833; see last week’s issue of The Town Line), used to “take walks with his students along the bank of the Kennebec or out to the thriving new settlement of Ten Lots in the western part of the town.”

(Marsh says the walk would have been about five miles one way.)

The intersection of Ten Lots and what is now Gagnon roads seems to have been the center of a distinctive 19th-century community. One source described area residents as very musical, with an instrument in almost every home and frequent song-fests.

PART TWO: UNION CHURCH AT TEN LOTS, 1836-1915

Davidson wrote that Ten Lots residents were at first members of Waterville’s First Baptist Church that Chaplin organized in 1818. Services were held part of the time in the village and part of the time in a schoolhouse in or near Ten Lots.

In 1830, Davidson wrote, one of several revivals that started in Ten Lots brought in ten new church members, including seven surnamed Bates. Another revival in 1838, he wrote, included Rev. Samuel Francis Smith baptizing 17 “young people” from Ten Lots in Messalonskee Stream – in December.

In 1836, the Oakland history says, the Ten Lots community built a Union Church where the present chapel is. The site is on the east side of Ten Lots Road, which runs north-south, on the south side of the intersection with Gagnon Road. It is about as close to the middle of Ten Lots as possible.

The 1836 date does not match information Davidson had from two sources, who said 44 people left the Waterville Baptist Church in 1844 (on Jan. 15, one source said) and established a congregation in West Waterville. Another source said services were held in a Ten Lots schoolhouse, which was later moved to Reward Sturtevant’s property.

Davidson dated the Union Church, probably erroneously, to 1846. He suggested two reasons for the split: the differences between the in-town residents, including college students and professors, and the mostly farmers from Ten Lots; and the travel distance from West Waterville to the village.

A picture of the Union Church, a plain rectangular wooden building, hangs in the entry of the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel.

After Milton LaForest Williams (see box) offered to fund a new chapel, the Union Church building had to get out of the way. Davidson wrote that it was disassembled, loaded onto oxcarts, and taken as a gift to Rome, where men from Ten Lots put it back together and added a steeple.

He summarized a Dec. 12, 1915, letter from Rome’s Baptist Church members thanking Ten Lots residents for the building and their help. The church was still standing when he finished his paper in May 2007.

Until completion of the new chapel, a nearby schoolhouse again did temporary duty for Ten Lots church services. This schoolhouse later became a summer kitchen at Asa Bates’ house, according to the Oakland history.

PART THREE: ASA BATES MEMORIAL CHAPEL, 1918-PRESENT

The Asa Bates Memorial Chapel is so close to the town and county lines that although the building is in Fairfield, part of the driveway is in Oakland.

Christi A. Mitchell, the Maine Historic Preservation Commission historian who wrote the application for National Register listing, called the chapel “an extraordinary example of small scale Classical Revival Architecture in a rural setting.”

(Readers might remember Mitchell’s name from earlier articles that used material from her thoroughly-researched applications; see The Town Line, March 11, March 18 and April 15, 2021).

The story-and-a-half building set on a brick foundation, with four Doric columns across its front, is “similar to a Roman temple in form,” Mitchell wrote. She further commented on its “crisp Roman lines” and compared it with Thomas Jefferson’s 20 Pavilions at the University of Virginia.

The chapel sits among mostly well-maintained mid to late 20th-century residences (a few older farms and 19th-cenury houses are interspersed). Mitchell wrote that “no other structure in the neighborhood commands such a presence.”

The chapel’s architect is unknown, Mitchell wrote. In George Bryant’s speech at the Aug. 13, 1918, chapel dedication, Bryant said the late E. T. Burrows (husband of a cousin of Williams) managed “the planning and erection of the building.”

Marsh speculates that Williams had a say in its appearance, perhaps, for example, in the choice of a ceramic-tile roof, which seems more California than local. She also says that his wife’s brother was an architect.

(This writer’s on-line search found three architects surnamed Andrews active in the early 1900s, but none was born in New York City, none had a father associated with stagecoaches and only one practiced, briefly, in any part of New York.)

Above the Doric columns, the triangle under the roof has a half-circle window – Christie called it a fan window. Behind each column is what Christie called a gray marble pilaster.

Cement steps – now covered by wooden steps – lead to the center of a cement porch and the double front door, with marble panels on the sides and a rectangular window with a “diamond pattern grill” above.

On each side of the front, visible between the columns, is a marble plaque with a square window, similarly patterned, above it. Each plaque has an incised inscription.

The north plaque donates the chapel “to the religious literary and social purposes of this Ten Lots community,” and says that Rev. Samuel Francis Smith preached in the building between 1838 and 1842. The south plaque says Williams gave the chapel and library in 1916 “in grateful memory of his grandfather and benefactor Asa Bates born 1794 died 1878.”

The front doors open into a small vestibule and then the main room, high-ceilinged, with tall sliding doors, wood on the bottom with glass above, that allow it to be divided. Christie wrote that the doors are custom-made of mahogany.

At the far (east) end of the room is a stage. The stage is under a flat arch decorated, Christie pointed out, with triglyphs and metopes. It has a trapdoor in the floor, but no wings.

(Wikipedia says: “Triglyph is an architectural term for the vertically channeled tablets of the Doric frieze in classical architecture, so called because of the angular channels in them. The rectangular recessed spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze are called metopes.”)

The north and south walls each have three tall nine-over-nine windows. Pastor Gene McDaniel recently repaired the windows, along with his father, Gary McDaniel, who did the reglazing. Chapel trustee Kay Marsh did the painting, and Howard Hardy offered encouragement.

To the right of the entrance is Williams’ library, a small room with bookcases on east and west walls. The books there now are a mixture of non-fiction – histories of the United States and of England and an enormous dictionary, for example – and fiction, including novels by Winston Churchill (the American writer, not the British statesman), Zane Grey, Gene Stratton Porter and Kate Douglas Wiggin.

The basement provides space for community meals, served from a generous-sized kitchen that shares the east end with the furnace room. There are three large windows on each side, below the corresponding windows on the main floor.

Building and furnishing the chapel cost $6,000 (Bryant) or $8,000 (Davidson). In addition, Williams gave $5,000 (Bryant) to be used to benefit the neighborhood and/or $10,000 to help maintain the chapel (Davidson).

When the chapel was finished, Williams donated it to the Ten Lots Union Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor, which on July 22, 1918, gave it in trust to the United Baptist Convention of Maine.

When the Christian Endeavor Society became inactive in the 1930s or 1940s, Davidson wrote, the United Baptist Convention became responsible for choosing three chapel trustees. Marsh says she and Hardy are currently the only two.

After years as a community center and chapel, hosting suppers, parties, plays, wedding and funerals, the chapel is now seldom used. Since the late 1960s it has been rented, mostly to religious groups who use it one or two days a week.

Marsh says the remainder of Williams’ trust fund pays for insurance on the building, and rental fees cover heat and lights. The current tenants have repainted the interior.

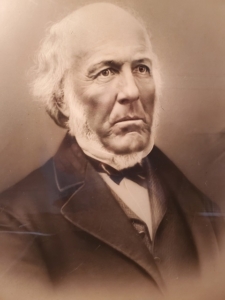

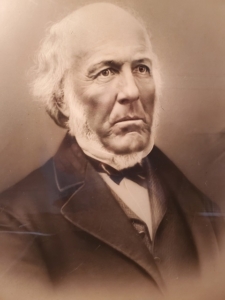

Asa Bates

Asa Bates

Ten Lots resident Asa Bates (1794-1878) married Fannie Stillman in 1818. One of their daughters, the Oakland history says, was Frances Diana, who married Henry Williams.

The Williams couple lived in what was then Petersburg (or Petersburgh), New York (near Plattsburg) where Fannie had been born in 1801. Asa Bates’ grandson Milton LaForest Williams (known as LaForest to his friends) was born there Aug. 20, 1851. In 1857, Marsh says, he, his mother (who died in 1864) and his two-years-younger sister came to Ten Lots to live with Asa Bates (his father’s fate is unknown).

Among documents Marsh has assembled is the text of a speech at the dedication of the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel by George Bryant, who had known Williams since the latter was 16 years old.

Bryant wrote that Williams worked on Ten Lots farms, where “with his bright and happy disposition, he was a general favorite.” He had jobs in at least two Oakland stores, one when he was 13 years old and later one Bryant established. His formal education ended after one term of high school.

After a brief time in Pennsylvania, Bryant wrote, homesickness brought Williams back to Maine in 1869. He learned telegraphy and began working for the Boston and Maine Railroad, in Portland, and points south, becoming head of the Union Station ticket office in 1888 and also treasurer of the Old Orchard Beach Railroad Company.

In 1893, Bryant wrote, Williams married Alice Maria Andrews, in New York City. He did not say, and Marsh does not know, how they met. Marsh found that Williams’ father-in-law had become rich in the stagecoach business.

Williams’ wife was not well, Marsh says. The couple had no children, and they moved to Pasadena (for her health?). Bryant wrote that she died there on Nov. 10, 1907.

After his wife died, Williams became a philanthropist. Bryant wrote that he had “honestly gained considerable wealth” “with no material assistance from any one” through his “natural ability and successful business management.” Marsh believes his wealthy father-in-law contributed.

Bryant’s dedication speech said Williams decided to have the chapel built to do something for the Ten Lots neighbors he remembered affectionately and to honor “the memory of his grandfather, The Grand Old Man, as he called him, who in kindheartedness, had been more than father and mother to him in his orphanhood.”

In addition to building the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel, the Oakland history says Williams helped pay for a fence and fountain at Lakeview Cemetery, and left $25,000 for education that was used to build Oakland’s Williams High School (1925 – 1969; now the oldest section of Milton LaForest Williams Elementary School, according to an on-line source).

Davidson recounts another example of Williams’ generosity to old friends. After the Civil War, he wrote, Lot Sturtevant’s grandson Reward Sturtevant learned that Williams owed $13 for groceries and wanted to clear the debt before he went away (perhaps to Pennsylvania?). Reward Sturtevant bought Williams’ 13 sheep for a dollar each.

Williams died May 5, 1919. In his will, he left $13,000 to Reward Sturtevant.

Main sources

Davidson, Jack, The Complete History of the Asa Bates Memorial Chapel (May 2007)

Marsh, Kay conversation and loan of documents.

Websites, miscellaneous.

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect that the people responsible for repairing the large windows were Pastor Gene McDaniel and his father, Gary McDaniel, who did the reglazing. Kay Marsh did the painting, and Howard Hardy offered encouragement.