Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Mail delivery – Part 1

by Mary Grow

Intercolonial mail started in the early 1700s in the major cities on the east coast of the future United States, and had reached Maine’s coastal towns before the Revolution. The national postal service was organized during the Revolution, with Benjamin Franklin the first Postmaster General. Alma Pierce Robbins wrote in her history of Vassalboro that mail service reached the central Kennebec Valley in the 1790s.

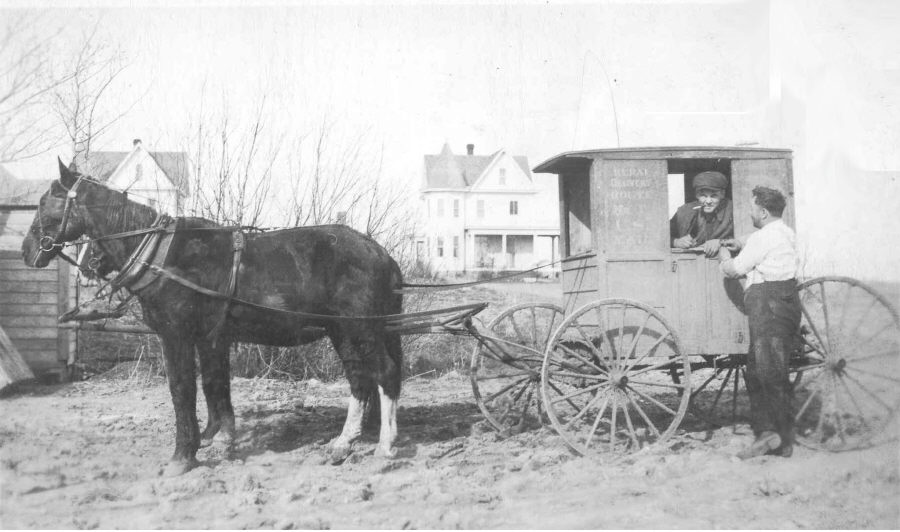

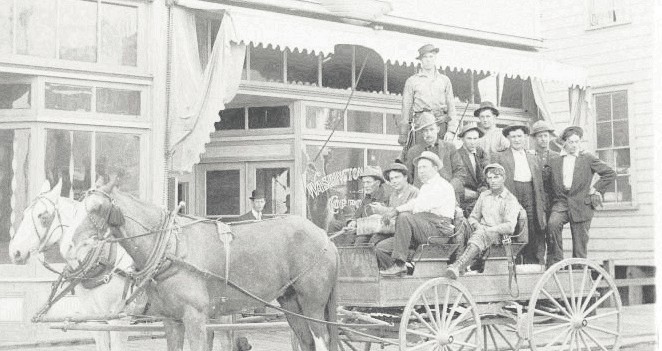

Mail carriers, employees of, or contractors with the federal government, delivered mail to local post offices by boat; on foot; on horseback; by wagon, stagecoach, sleigh or other conveyance; later by railroad; and later still by truck or car. Spread-out towns with multiple population centers had multiple post offices. Most were in stores, some in private homes.

Alice Hammond, in her history of Sidney, described two methods of mail delivery by stagecoach: if a post office were on a stagecoach route, the coach dropped off the mail, but for post offices not on a coach route, the federal government hired a responsible person to meet the coach and bring the mail to the post office.

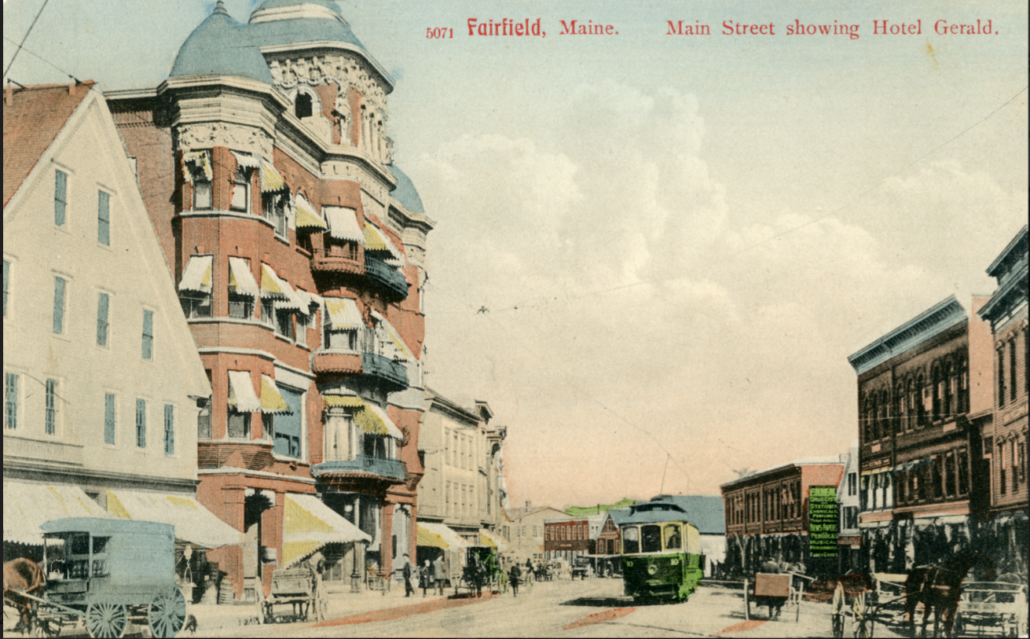

Vassalboro had six post office in the early 1800s, Robbins wrote. Hammond found Sidney also had six, the first opened in 1813 and the sixth in 1891. The latter remained open for only 11 years. The Fairfield bicentennial history says Fairfield had seven.

Milton Dowe’s Palermo history says there were post offices in North Palermo, East Palermo and Center Palermo, in addition to the one in Branch Mills, the village shared by Palermo and China. Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history lists four post offices in Benton, four in Windsor, three in Clinton and two in Albion. Until recently, Augusta and Waterville apparently had only one post office each.

Postal charges were initially determined by weight plus distance, according to the China bicentennial history. The 1799 charge for a one-page letter was eight cents within 40 miles; the fee increased progressively to 25 cents beyond 500 miles. New rates in 1845 were five cents for one page within 300 miles, doubled to 10 cents beyond 300 miles. At first the recipient paid the postage. In 1851 the U. S. Congress set up a two-tier system, charging less if the sender prepaid, and beginning in 1856 everyone was expected to pay in advance.

Initially the postal service was a government department (since 1970, it has been an independent agency of the federal executive department). Until postal service employees came under the civil service system, positions were political patronage jobs; consequently, a change in Washington, D. C., often had local consequences.

The presidency changed from one party to another in 1840 (Whig John Tyler succeeded Democrat Martin Van Buren), 1844 (Democrat James Polk), 1848 (Whig Zachary Taylor), 1852 (Democrat Franklin Pierce), 1860 (Republican Abraham Lincoln), 1884 (Democrat Grover Cleveland), 1888 (Republican Benjamin Harrison) and 1892 (Democrat Cleveland again).

A review of Kingsbury’s lists of postmasters in central Kennebec Valley towns shows no clear correlation between elections and changes in postmasters. At least eight new postmasters were appointed in the spring of 1885, after Cleveland took office, and more than a dozen in the spring of 1889, high but not excessive numbers. By the time Cleveland was re-elected and had time to undo Harrison’s appointments, if he wanted to, Kingsbury had published his history.

Ruby Crosby Wiggin, in her history of Albion, confirmed the political influence. From the time the Albion post office was established, probably in March 1825, until after 1914, a Republican national administration meant Republican local postmasters and a Democratic administration meant Democratic postmasters, she wrote.

The China bicentennial history says that in South China in the late 1800s, storekeeper Wilson Hawes was postmaster during Republican administrations, but when the Democrats were in power the post office moved westward to Tim Farrington’s store.

The list of South China postmasters in the history’s appendix correlates the postmastership with the presidential election, but it shows no switching back and forth. It says Farrington was appointed April 17, 1893, and Hawes April 12, 1897 (Hawes served until 1919). Democrat Grover Cleveland’s second term as president was from 1893 to 1897; Republican William McKinley succeeded him in 1897.

Augusta had one of the first post offices in the central Kennebec Valley, started in 1789 or 1794 (depending on the source). Charles Nash, author of the Augusta chapters in Kingsbury’s history, wrote that Postmaster James Burton was appointed Aug. 12, 1794, and that his house was where Meonian Hall stood in 1792.

(Augusta’s current Museum in the Streets website says Meonian Hall replaced the Burton House where the first post office opened in 1789. The Hall was an Italianate structure built by James North in 1856 and used for public events – Civil War rallies, plays and more. Frederick Douglass spoke there on April 1, 1864.)

Burton served as postmaster until Jan. 1, 1806, when he was “removed for party reasons,” Nash wrote. Among his successors was his son Joseph.

The Museum in the Streets includes a description of Augusta’s 1890 “Castle,” at 295 Water Street, one of the earliest buildings this writer has found built specifically as a post office. The website calls it “Richardsonian Romanesque” in style, 32,000 square feet, made of Hallowell granite, “with a corner tower, Roman arches, [and] a winding staircase.”

The “Castle” was the city’s main post office until the 1960s, the website says. Now called the Olde Federal Building, it has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974.

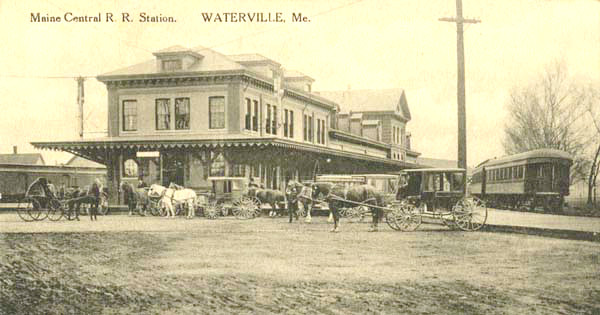

In Vassalboro, Robbins surmised that the first mail deliveries were probably by boat up the river. Stagecoaches took over early in the 1800s. In 1825, Robbins said, there were two mail deliveries a week from Augusta to Waterville. By 1897, a postmaster’s report said there were six deliveries a week.

The first post office in Vassalboro was at Getchell’s Corner, also called Vassalboro Corners (an important village from the town’s early days until the 20th century). Kingsbury wrote that the office opened April 1, 1796. Brown’s Corner, now Riverside, opened Jan. 18, 1817; in September 1856 it was moved from Brown’s store to where it stood when Kingsbury finished his history in 1892; and in January 1866 it was renamed Riverside. East Vassalboro’s post office opened March 26, 1827, and North Vassalboro’s March 22, 1828.

The village at Cross Hill in southern Vassalboro was first served by a Mudgett Hill post office established Feb. 2, 1827, near Three Mile Pond and from May 3, 1860, by the Cross Hill post office, located in a store. Nearby Seward’s Mills (as Kingsbury spelled it) had the Seward’s Mills post office from October 1853 until Oct. 30, 1889. The Mudgett Hill office was renamed South Vassalboro in or before 1859. The first postmaster, Kingsbury noted, had married Hannah Whitehouse, and his successors until 1892 all had the surname Whitehouse.

Kingsbury wrote that Winslow’s first post office opened July 1, 1796, with Asa Redington postmaster. Kingsbury gave no specific location. The second post office opened April 18, 1891, at Lamb’s Corner; Lizzie Lamb was appointed postmistress May 20. (The contemporary Google map identifies Lamb’s Corner as the intersection of Route 137 [China Road] with Maple Ridge and Nowell roads, in southeastern Winslow.)

Kingsbury added that Lizzie (Furber) Lamb was the widow of Charles Lamb (1829-1883), whose parents settled in Winslow in 1821. Writing in 1892, he described her as running “the homestead farm.”

Whittemore’s Waterville centennial history says in the 1700s the town, part of Winslow until June 23, 1802, had sporadic mail service, with carriers traveling by snowshoe in the winter. Kingsbury wrote that when the Waterville post office was established Oct. 3, 1796, Asa Redington was the first postmaster there, as well as in Winslow. The two were evidently not the same establishment, because Kingsbury’s lists of successive postmasters are not duplicates. Winslow’s second postmaster was Nathaniel B. Dingley, installed in 1803; Waterville’s was Asa Dalton, installed in 1816.

Whittemore’s history says in 1806, Peter Gilman established a stage line between Hallowell and Norridgewock with a stop in Waterville, ensuring regular two-day-a-week delivery.

The history includes a reminiscence by William Mathews, born in 1818, whose family lived on Silver Street for at least part of his childhood. By the 1820s, the mail stage from Augusta arrived daily about 11 a.m., he wrote, announced by the driver’s blowing his horn. The mail stop was at Levi Dow’s Main Street tavern.

Palermo’s earliest residents had to get their mail in Wiscasset, Millard Howard wrote. Palermo’s first postmaster, John Marden, was appointed in 1816. Later, Hiram Worthing served as Branch Mills postmaster for 47 years (except for two years during James Buchanan’s 1857-1861 administration); his son Pembroke succeeded him, and the job remained in the Worthing family well into the 20th century.

In Harlem, later China, the bicentennial history says Japheth C. Washburn was in charge of the mail early in the 19th century. Before 1810, his 10-year-old daughter Abra and eight-year-old son Oliver Wendell rode horseback through the woods to bring mail from Getchell’s Corner, in Vassalboro.

Around 1812, the history continues, the post office began contracting with adult mail carriers. That year the Vassalboro service was supplemented by a weekly Augusta to Bangor run, still extant in 1827 after the Town of China was created. In 1816, the history says, a mail route from Augusta to Palermo went through Brown’s Corner (location unspecified) and Harlem (later China). In 1820, two new routes were established, from Hallowell and from Vassalboro.

In 1837, the history says, three mail routes crossed the town: the driver of the daily coach from Portland to Bangor and the weekly horseman from Waterville to Palermo stopped in China Village, and three times a week the man driving a wagon or sulky delivered mail in South China on his way from Augusta to Belfast.

The China Village post office was established in 1818 in Washburn’s store, with Washburn the first postmaster.

South China had a post office from 1828, according to Kingsbury, first located in Silas Piper’s store with Piper the postmaster. Kingsbury wrote that Piper collected 13 cents worth of postage and earned 30 cents for his work during the first three months of his post

mastership.

The Weeks Mills post office was started in 1838, and was served by stagecoach for most of the 19th century.

Windsor’s first post office probably opened in 1822 at Windsor Corner, according to Kingsbury. He wrote that Postmaster Robert Williams’ commission dated from July 17 that year. South Windsor acquired a post office May 5, 1838; West Windsor, Sept. 8, 1873; and North Windsor, June 3, 1884.

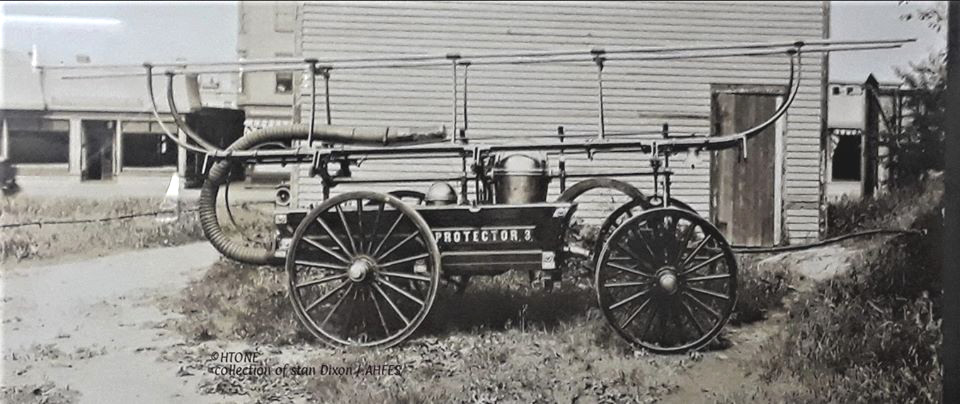

While the Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington railroad served Windsor, Palermo, China, Albion, Vassalboro and Winslow in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (see The Town Line, Sept. 17, and Sept. 24), the government mail contract was an important source of income. Local histories give few details of mail service; there are occasional references to revenue, and Clinton Thurlow wrote that at one point, Weeks Mills got two daily mail deliveries by train, at 7 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Next week: more about mail service.

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E. , Palermo, Maine Things That I Remember in 1996 (1997).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Robbins, Alma Pierce , History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.