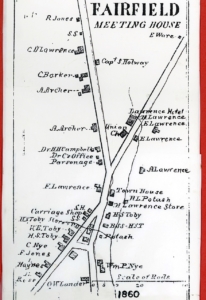

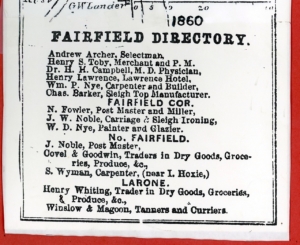

Allen, Vickery, Gannetts

In addition to the nationally and internationally famous people profiled earlier in this series (James G. Blaine, Rufus Jones, Elijah Parish Lovejoy, Senator George Mitchell), other central Kennebec Valley residents have made significant contributions beyond the local area.

E. C. Allen

An Augusta website gives Edward Charles Allen, known as E. C. Allen, credit for starting the publishing industry that gave Maine’s state capital the title “mail order magazine capital” from the 1870s into the 1940s. Allen and his successors created, printed and mailed magazines and other periodicals. Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that E. C. Allen Publishing was known throughout North America and its publications had subscribers in English-speaking countries all over the world.

Kingsbury said Allen was born on a farm in what was then Readfield on June 12, 1849 (his family’s part of town became Kennebec in 1850 and in 1854 took its present name, Manchester). He was educated in local schools and at Kents Hill Seminary and started an advertising and sales business when he was 16 that he continued after he moved to Augusta in 1868.

In 1869 Allen started writing, editing and publishing his first magazine, an eight-page monthly named The People’s Literary Companion. Two of his novels, published as well-received serials in the magazine in 1871, were titled Lillian Ainsley; or, Which Shall Triumph – Right or Might? and Light and Darkness; or, The Plots and Works of the Tempter.

One of Allen’s ideas was to offer new subscribers a gift, often a steel engraving. In 1871 he opened an art publishing business in Portland that provided engravings.

At first Allen worked with an Augusta printer. When his needs outgrew the printer’s resources, he rented a building and opened his own printing business. In 1879, he oversaw construction of the E. C. Allen Publishing Company building at the intersection of Water and Winthrop streets.

The 1886 Gazetteer of the State of Maine says the building was six stories high and 53-by-65 feet, with a six-story addition made of granite, brick and iron with two-foot-thick walls. Although, the account says, 16 printing presses, a bindery and other machinery ran constantly, the buildings didn’t shake.

Fire suppression was installed on every floor, the Gazetteer article says. The steam elevator could carry a five-ton load from the first to the sixth floor in half a minute. The rooftop steam whistle that signaled shift changes kept such perfect time that people set their clocks by it.

In 1880, Allen added a six-story office building across the intersection, with a tunnel under Water Street to connect it to the older building. It was demolished in 1987, according to Augusta’s Museum in the Streets.

A contemporary on-line site says after the publishing industry faded away, the first Allen building housed stores and offices until late in the 20th century, listing Farrell’s and the Village Shop, two clothing stores, as tenants until the late 1980s. By 2013 the building was in poor condition; a new owner rescued it and turned the upper floors into apartments, the on-line site says.

In 1885, Allen had about 500 people working for him. A friend described him as a respected employer who earned himself a fortune and paid his workers generous and steadily increasing wages.

Company publications included the magazines Golden Moments, Home and Fireside and Sunshine; at least one magazine for young people, Our Young Folks’ Illustrated Paper; printings of the Bible; and history books and biographies. Kingsbury’s history says within a month after James G. Blaine was nominated for president in 1884, E. C. Allen Publishing produced a 500-page Life of James G. Blaine (it sold 200,000 copies).

Kingsbury wrote that because of the volume of mail Allen’s company generated, Augusta had a first-class post office and its 1890 granite post office building (see The Town Line, Oct. 15). He gave examples: 1.2 million magazines and papers produced a month, most mailed to subscribers; an average annual postage bill of $100,000 for a 10-year period, and $144,000 one year; more than 1,600 tons of paper mailed in one year; and Allen’s personal mail that averaged 1,500 to 2,200 letters a day (and reached 12,000 one exceptional day).

Allen was involved in local banking and other businesses. He chaired the Augusta Board of Trade for three years, during which he led the enlargement of the capitol building.

He traveled extensively in Europe, mostly on business. Returning from his 24th trip in July 1891, he caught a cold that developed into pneumonia and died at the Parker House, in Boston, on July 28, at only 42 years old. After a funeral that Kingsbury wrote was the largest anyone could remember in Maine, he was buried in Forest Grove Cemetery.

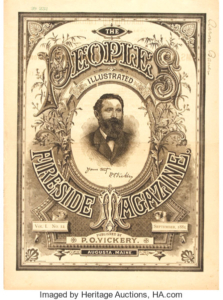

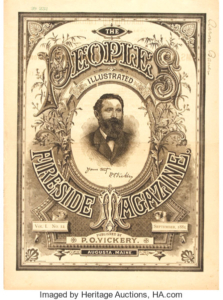

Cover of The People’s Fireside Magazine with the photo of P.O. Vickery.

In October 1874 a printer named Peleg Orison Vickery (1836 or 1837-1902 or 1908) started Vickery’s Fireside Magazine, described as a magazine of light fiction and a mail-order catalog. This popular publication was followed in March 1876 by the Illustrated Family Monthly (closed in 1885); in 1881 by Happy Hours; in 1883 by Hearth and Home, also known as Back-log Sketches, a 16-page monthly by 1892; and in 1890 by Good Stories.

Personal information about Vickery is scarce on the web, with even his birth and death dates listed inconsistently. A Maine native, he came to Augusta when young and apprenticed as a printer before starting his own successful printing business.

In 1882, Vickery’s son-in-law John Fremont Hill (later a two-term governor of Maine, 1901-1905) became his partner and the business manager for Vickery and Hill. By 1892, Kingsbury wrote, the business had a full-time staff of about 75 people, significantly increased by temporary employees when needed. Vickery and Hill had branches in Boston, New York and Chicago.

One source describes Vickery as a politician as well as a publisher, and several say he served as Augusta’s mayor for three terms (1880-1882). His business interests included ownership for some years of the hotel called the Augusta House, according to Thelma Goggin’s 1969 University of Maine at Augusta history term paper titled One Hundred Thirty Eight Years at the Augusta House (available online through Digital Maine).

In 1895, Boston architect John C. Spofford designed the four-story Vickery Building at 261 Water Street to house Vickery and Hill. Wikipedia describes it as a masonry building with a granite – white Hallowell granite, another source adds — façade in Italianate commercial style and a handsome cornice topped by a parapet.

The Vickery building has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984. After more than a century as office and commercial space, this spring it re-opened as a 23-unit apartment building.

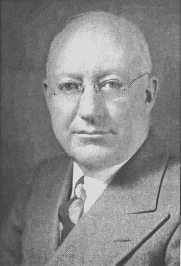

The best-known Augusta publishers were William Howard Gannett (1854-1948) and his son and grandson.

Guy P. Gannett

William Gannett was the 12th of 14 children in a poor family. An on-line genealogy says he had to leave school when he was eight years old and start working, apparently in a toy store. The writer of the article described Gannett as self-educated and self-reliant, physically strong, intelligent, ambitious, willing to try new ideas, kind and charitable.

Partnering with a man named Morse, in 1887 or 1888 Gannett added to the retail business a magazine called Comfort that he intended as a vehicle to sell a nerve tonic he had invented called Giant Oxien. At that time magazines were printed in black and white; Gannett wanted color. In 1892 he commissioned the New York printers Hoe & Company to design and build, for $50,000, a color press that could produce Comfort fast enough to meet his needs.

Comfort’s first color issue was mailed in July 1895 to more than a million subscribers; later it had almost three million. It continued until 1942.

Augusta’s First Amendment Museum website quotes Gannett’s account of how he named the magazine: the word suddenly came into his mind, and he realized “…that’s it, for everyone wants Comfort.”

The Museum website reproduces a Comfort ad for Oxien Electric Plasters. The ad claims they cure a long list of maladies, from aches and pains, indigestion and “female disorders” to malaria, consumption (tuberculosis) and epilepsy.

The magazine’s ads, which invited readers to buy their products, were accompanied by advice columns, fashion updates and recipes, poems and romantic fiction and news articles. Gannett promoted circulation by offering subscribers gifts if they signed up other subscribers.

An online source says Comfort absorbed Allen’s People’s Literary Companion in 1907.

The Museum website says Gannett was fascinated by air travel. He learned to fly hot-air balloons and airplanes and knew Charles Lindbergh. Civic-minded, he financed the restoration of Fort Western, started Augusta’s Winter Carnival (a photo shows him as Carnival King in 1923) and donated 475 acres for a game preserve that is now the Howard Hill Conservation Area.

In 1878 Gannett married Sarah (or Sadie) Neil Hill, of Skowhegan. They had three children, Grace B., Guy Patterson and Florence L.

Guy Patterson Gannett (1881-1954), attended Augusta schools and Phillips Andover Academy, in Massachusetts. He left Yale after this freshman year in 1901 or 1902 (sources differ) to join and then succeed his father. In 1921, he founded Guy Gannett Publishing Company. The company was perhaps best known in Maine for its newspaper chain that included three Portland papers, the Kennebec Journal, in Augusta, and the Morning Sentinel, in Waterville.

Guy Gannett married Anne J. Macomber on June 6, 1905, according to an online genealogy. Other sources say the house William Gannett built for the couple in 1911 at 184 State Street, beside the Blaine House, was a wedding present. Consistent with William Gannett’s interest in air travel, the stucco Mediterranean-style house was up to date, with electric lights, an elevator, a central vacuum system and “the first automobile garage in the city.”

Guy and Anne had three children, Alice Madeleine (later Gatchell), John Howard and Jean (later Hawley).

John Howard Gannett was born Aug. 23, 1919, and spent his first years in the Augusta house, according to his obituary. He attended schools in Augusta, Portland and Cape Elizabeth (the family moved to Cape Elizabeth sometime after Guy Gannett bought two Portland newspapers in 1921); graduated from The Governor’s Academy (previously, Governor Dummer Academy), in Massachusetts, in 1939; and studied printing at Wentworth Institute, in Boston, until he joined the army in June 1941.

John Gannett married Patricia Randall, of Conner, Florida, on July 5, 1943, during his army service. The couple settled in Augusta in 1949, where John was a vice-president of Guy Gannett Publishing Company and general manager of the Kennebec Journal printing division.

John was interested in machinery, especially trains, including Maine narrow-gauge railroads, and boats. As Commodore of the Kennebec River Yacht Club, when local interest faded he led the club to donate its land to the city, where it became a park and the Eastside Boat Landing. In Manchester, he developed Cobbossee Marina, on Lake Cobbosseecontee, as a family home and jet-boat business.

After John retired from publishing, he and Patricia moved back to Conner, Florida. They spent three years as long-haul truckers before retiring again. Patricia died in 2012; John died July 16, 2020, at almost 101 years old.

Guy Gannett Communications was owned by a family trust from 1954 until it was sold in 1998. Since then, its properties have since gone through several changes of ownership.

John and Patricia Gannett also had three children, Terry Gannett Hopkins, Patterson R. Gannett and Genie Gannett (married to David Quist). In December 2015, the two daughters, Terry and Genie, bought the Gannett house, which had been the State Planning Office building, intending to establish a museum to honor their family business and their grandfather’s dedication to press freedom.

A quotation from Genie Gannett on the Museum website explains that they quickly realized all five First Amendment freedoms – press, religion, speech, assembly and petition – were inextricably related, and their project became the First Amendment Museum.

The website, https://firstamendmentuseum.org includes information on the museum’s past, present and planned future, an invitation to book a (masked) guided tour and an email address and telephone number.

[Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to correct the date on which Genie Gannett, Guy Gannett’s granddaughter, and her sister bought the Gannett family house to 2015, not 1915.]

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.