Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Notable citizens – Conclusion

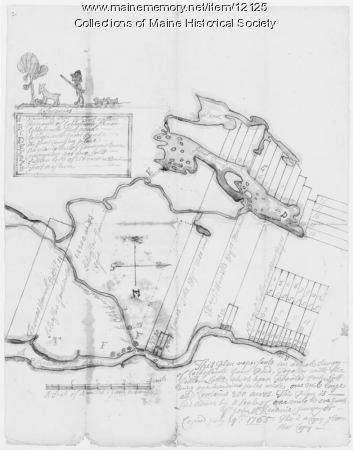

The Old Meeting House, built in 1834, still stands in St. Louis County. Elijah Lovejoy preached there before moving to Alton, Illinois, in 1837.

by Mary Grow

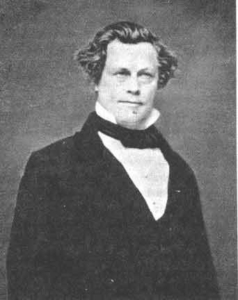

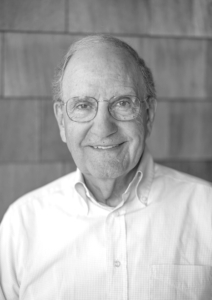

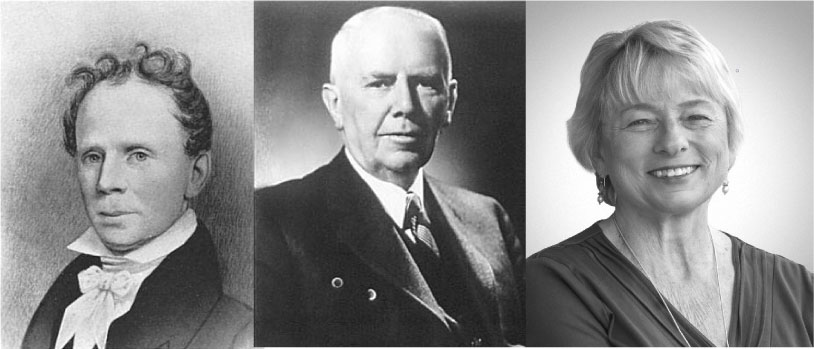

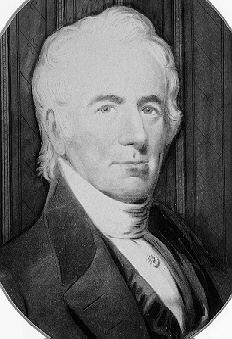

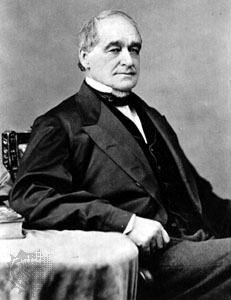

Elijah Parish Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was born Nov. 9, 1802, in Albion. His grandfather, Francis Lovejoy, was one of the town’s first settlers. His father, Daniel, was a Congregational preacher who, according to extracts from the sermon preached at his funeral, was a good man and a good minister, but was sometimes too carried away by enthusiasm to be tactful and was subject to periods of depression.

Lovejoy was the oldest of nine children born to Daniel and Elizabeth (Pattee) Lovejoy, seven boys and two girls. Three boys had died by early 1832. Elijah’s sisters were Sibyl and Elizabeth, named in an Aug. 18, 1833, letter of condolence Elijah wrote after the death of their father.

Younger brother Joseph Cammett, born in 1805 and the next brother, Owen, born in 1811, wrote a memoir about Elijah, published in 1838 by the New York Anti-Slavery Society. It consists mainly of collections of his writings, including long poems (which he wrote from an early age), letters and newspaper pieces.

Joseph was a pastor in Old Town and later in Massachusetts. He is listed on line as author of several other works, including other biographies and a collection of speeches against alcohol consumption.

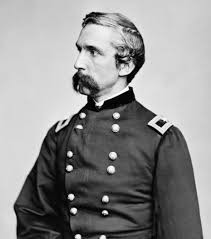

Owen joined Elijah in Illinois and was present when his brother was killed. He became an active abolitionist, guiding escaping slaves along the underground railroad. Friends with Abraham Lincoln, he helped create the Republican Party and represented it in the state legislature in 1854 and in the U. S. House of Representatives from March 4, 1857, until his death March 25, 1864.

John Ellingwood, youngest of the brothers, was born Oct. 13, 1817. He too was in Alton with Elijah in the mid-1830s; whether he was present when his older brother was killed is unclear. An on-line genealogy says he went to Clay City, Iowa, in 1839, and later to Scotch Grove, Iowa. He married twice to women born in Manitoba; his first wife, Margaret Livingston, died in 1869, and in 1871 or thereabouts he married Joanna or Johana McBeath. The genealogy describes him as a farmer, postmaster, U. S. consul in Peru and, in the 1880 census, the railroad depot agent in Scotch Grove.

The senior Daniel Lovejoy supported education for his sons. Biographer John Gill said Elijah taught himself to read from the Bible when he was four; he was able to read and memorize with unusual speed. He attended the local district school, Monmouth Academy, China Academy and from 1823 to 1826 Waterville (later Colby) College. While attending college, he was simultaneously headmaster of the college’s preparatory Latin School (later Coburn Classical Institute).

After graduating in September 1826 as class poet and class valedictorian, Lovejoy spent the winter as a China Academy teacher and then decided to move west. He spent part of 1827 in Boston and New York trying to earn money for the trip; asked for and got help from Jeremiah Chaplin, then president of Waterville College; and by the end of 1827 was settled in St. Louis, Missouri.

There he taught briefly before switching to the newspaper business, a website says because editors appreciated the poems he sent them. As a newspaper writer and editor, he met community leaders and especially anti-slavery activists.

Missouri was a state in which slavery was legal, a so-called slave state. It had been admitted to the United States in 1820. Maine, where slavery was not recognized, was admitted simultaneously to maintain the equal balance of slave and free states in Congress.

In 1832 Lovejoy had a religious conversion. He came back east to study at Princeton Theological Seminary, was ordained a Presbyterian minister in April 1833, and was promptly offered support if he wanted to open a Presbyterian newspaper in St. Louis.

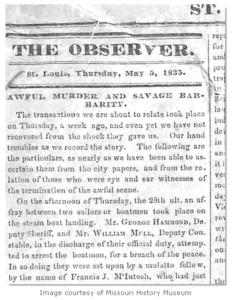

The St. Louis Observer began publication in November 1833. From the beginning it served partly as an outlet for Lovejoy’s views. Early issues attacked the Catholic Church and objected to tobacco and alcohol use. His anti-slavery writings began by 1835.

As opposition became more violent, Lovejoy repeatedly expressed his conviction that he was doing God’s will. Therefore, he believed he should not, indeed could not, retreat, even when threats against his life became direct and immediate.

Though opposed to the practice and principle of slavery, Lovejoy made it clear that he thought immediate and unconditional freedom for all slaves a bad plan that would be cruel to them. He sympathized with gradual emancipation and with colonization projects that had been sending free Black people to Liberia since the 1820s.

By the mid-1830s, biographer Gill wrote, mob violence was becoming an increasingly common way for anti-abolitionists in the northern states to express their outrage at abolitionists. Victims included black and white people, especially those who spoke or wrote publicly in favor of abolition. Lovejoy condemned mobs and extra-legal acts on both sides, and sometimes criticized abolitionists for provocative speeches and actions.

On Nov. 5, 1835, Lovejoy returned from an out-of-town trip to write an open letter to his fellow citizens rebuking them for a series of resolutions passed at an October public meeting, including one to ban anti-slavery messages. He insisted on free speech and a free press and announced that he would not amend or retreat from his principles even to save his life.

In the final paragraphs, he asked those who disagreed him with to respect the other people and the property associated with his paper. “I alone am answerable and responsible for all that appears in the paper, except when absent from the city,” he wrote.

And “If the popular vengeance needs a victim, I offer myself a willing sacrifice.”

Meanwhile, on March 10, 1835, Lovejoy sent his mother a letter that began: “I am married.” Apparently he had not told her previously about Celia Ann French, who was originally from Vermont and lived in St. Charles, northwest of St. Louis, because he described his new wife’s appearance and personality.

After pro-slavery mobs had destroyed his printing press three times, in the spring of 1836 Lovejoy moved the paper’s headquarters across the Mississippi River from Missouri to Alton, Illinois.

Although Illinois was a free state, many Alton residents were pro-slavery, so Lovejoy’s Alton Observer was as unpopular as the Missouri version. Here, too, mobs repeatedly smashed his printing press, while he continued to be outspoken in his defense of gradual abolition and of freedom of the press, insisting on his right to publish the paper as he saw fit.

The Alton Observer was not merely a propaganda piece, according to Gill; it was a real newspaper, with a multi-state circulation of more than 2,000. Lovejoy welcomed contributions from area writers and took articles from other papers. He discussed world news and history and provided useful information for local farmers, their wives, their children and their pastors. Sometimes he included humorous pieces; Gill quoted a description of a fight between a spider and a grasshopper on the planet Saturn, allegedly viewed through the latest improved telescope.

Lovejoy was also minister at the Presbyterian church in Alton. There he organized the first Illinois Antislavery Congress on Oct. 26, 1837.

Less than two weeks later, on Nov. 7, a pro-slavery mob attacked the warehouse where Lovejoy had stored a brand-new replacement printing press. There are many dramatic accounts of the scene. Lovejoy and a few supporters were inside; gunfire was exchanged, with casualties on both sides, including Lovejoy. He was buried quietly two days later, on what would have been his 35th birthday.

News of his death made him an instant martyr to the anti-slavery cause and to supporters of press freedom. Gill said among others inspired were John Brown, leader of the 1859 raid on the U. S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, and Wendell Phillips, whose speech at the Dec. 8, 1837, abolitionist meeting in Boston’s Faneuil Hall brought a divided audience unanimously to support a free press and to condemn the Alton mob.

Celia Ann Lovejoy was devastated by her husband’s death; she could not attend his funeral. By then she had a son, Edward Payson Lovejoy, and was again pregnant. The second child apparently did not live, although one on-line genealogy lists (without dates) a daughter named Charlotte.

John J. Dunphy, of Alton, wrote in 2013 that Celia and Edward lived with the Maine Lovejoys briefly. She reconnected with Royal Weller, a supporter of her husband’s paper who had moved to Detroit, and they were married, in Michigan, in December 1841.

Weller started a lawsuit against Owen Lovejoy that turned the Lovejoy family against him and Celia, and Celia’s mother had never approved of her daughter’s first marriage to an abolitionist, so Celia and Edward ended up estranged from both families. She separated from Weller, and mother and son moved to Iowa and later to California, where Celia died July 11, 1870, with Edward by her side.

There are monuments to Elijah Lovejoy in Albion and in Alton. Colby College has a Lovejoy building and since 1952 has given an annual Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award to a reporter, editor or publisher who continues Lovejoy’s heritage of courage and independence.

Main sources:

Gill, John Tide without turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the press, 1958

Lovejoy, Joseph C. and Owen A Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy; Who Was Murdered in Defence of the Liberty of the Press, at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837. 1838

Tanner, Henry The Martyrdom of Lovejoy. An Account of the Life, Trials, and Perils of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy Who was Killed by a Pro-Slavery Mob, at Alton, Ill., on the Night of Nov. 7, 1837. By an Eye-Witness. 1881

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby Albion on the Narrow Gauge, 1964

Web sites, misc.

Next: the story of a Pennsylvanian who moved north to start his political career, and because he chose to settle on the bank of the Kennebec instead of the Merrimack or the Winooski, gave his opponents a slogan that’s familiar after more than 130 years.