Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Crossing the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River has been known to occasionally overflow its banks. In this photo, houses of the residents at the Head of Falls, in Waterville, managed to survive the great flood of 1936. The houses were later razed in the name of urban renewal. The famous two-cent bridge can be seen at right, and the water tower of the former Wyandotte-Worsted textile mill can be seen in the background. The river has also had catastrophic floods in 1973 and 1987. (photo courtesy of Waterville Historical Society)

by Mary Grow

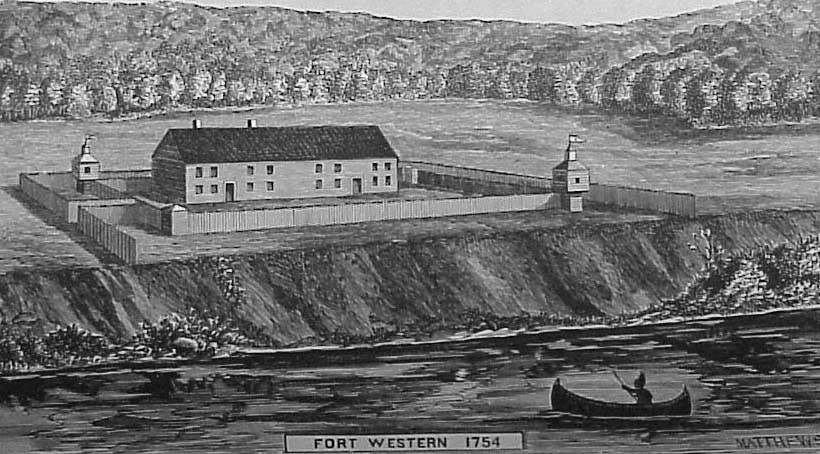

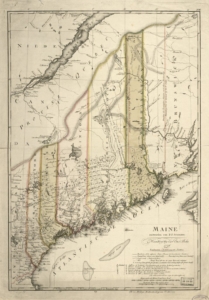

The Kennebec River was a highway into the interior of Maine, but it was also a barrier to travel. The Native Americans found safe places to cross; European settlers did the same, learning either from the Natives or by trial and error. As early as 1757, Kingsbury’s History of Kennebec County refers to “Riverside or Lovejoy’s ferry,” on the river’s east bank between Fort Western and Fort Halifax, in the section of Vassalboro still called Riverside.

Farther south, the river divided what was at first Hallowell and later became the City of Augusta. Kingsbury says people crossed by Pollard’s Ferry, started in 1785 and running from the foot of Winthrop Street to the old Fort Western site, until it was superseded in November 1797 by the first bridge across the river.

This bridge, like most of the other early bridges, was financed by private enterprise. Investors formed companies of various kinds, some selling stock. In Kingsbury’s history, it appears that few if any made money from their enterprises.

The first Augusta bridge, Kingsbury says, collapsed in June1816. A ferry ran again for two years while a second bridge was built; that one burned in April 1827. The third bridge was completed in August 1828.

The first three bridges were toll bridges, until the City of Augusta bought the third one in 1867 and eliminated tolls. Kingsbury cites an undated list of toll rates, which range from two cents for a pedestrian to 35 cents for a “coach, chariot, phaeton, or curricle.”

According to Alice Hammond’s History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 and Alma Robbins’ History of Vassalborough Maine 1771-1971, there were two ferries across the Kennebec, first to the western part of Vassalboro and after 1792 to the separate town of Sidney. The two towns have never been connected by a bridge, although in 1915, Hammond writes, Sidney voters approved building a bridge “to be located east of the junction of the River and Church roads.”

However, they passed over – took no action on – the next article, which would have appropriated money for the project. When the idea was presented again in 1916 it got no support.

Lovejoy’s ferry at Riverside was the southern and the earlier Vassalboro ferry; the other was farther upstream at Getchell’s Corner. Vassalboro voters discontinued roads to both ferries in the 1870s and 1890s, but the ferries continued to operate through the 1920s, according to Hammond. In the 1890s they usually ran from 200 to 250 days a year. By then, a main purpose was to transport people and goods from Sidney to connect with the railroad running through Vassalboro.

In 1889, Hammond writes, the county commissioners divided ferry costs between the two towns, making Vassalboro responsible for 3/8 of the costs of the Riverside ferry and 5/8 of Getchell’s Corner and Sidney responsible for the remaining percentages. The ferry operators were paid $1 per day in the 1890s. Town reports show that the ferries ran deficits, up to $200 some years, and that the two towns were hesitant to cover them.

In 1919, Hammond says, the Sidney town report noted that the town owed Vassalboro $566.62 for 10 years of ferry money, and voters called for an investigation. In 1920, she says, Sidney paid Vassalboro $430.74.

She says each ferry had two boats, a rowboat for passengers and a large flat-bottomed boat that carried horses and wagons and later automobiles.

Robbins’ History includes a photo labeled “The Ferry Vassalboro, Me. 1909.” It shows a flat barge with a small triangular sail putting out from a wooded bank carrying a cart drawn by two white horses, with someone at the horses’ heads and at least one person in the cart.

Hammond quotes two residents who remembered the Riverside ferry, Norman Haskell, of Sidney, and Norman Fossett, of Vassalboro. Haskell, who lived near the landing as a young man and sometimes worked the ferry, commented on the skill needed to get the boat across the river and docked. The crossing took half an hour or longer, he remembered.

Haskell went to high school in Augusta, Hammond writes. To go home on weekends he took the train north to Riverside and the ferry to Sidney. At Riverside a Sidney man named Alphonso Clark had a barn where he stored hay from Sidney for the Boston market.

Fossett told Hammond the boats were docked in Sidney, so the Riverside terminal had a horn that Vassalboro people blew to call the ferryman. Youngsters used to think it amusing to call him over and then hide.

Hammond says the Getchell’s Corner ferry was not rowed, but pulled across the river on a cable. It transported Sidney-grown corn to the Burnham and Morrill cannery, in North Vassalboro, and Sidney students to Oak Grove School.

In 1922 and 1923, Hammond writes, a former student remembered the fare as 10 cents one way, 15 cents round-trip. Transporting a team on the large boat cost 50 cents.

By 1922, the combined deficit for the two ferries was over $1,000. In 1925-26, Sidney and Vassalboro town meeting warrants asked voters to close the ferries. Apparently at least one town refused, because service continued through 1931, with Burnham and Morrill contributing funds. The 1934 Vassalboro town report records that Vassalboro and Sidney split a $106 bill for trucking Sidney corn to the B & M cannery in 1933, Hammond writes.

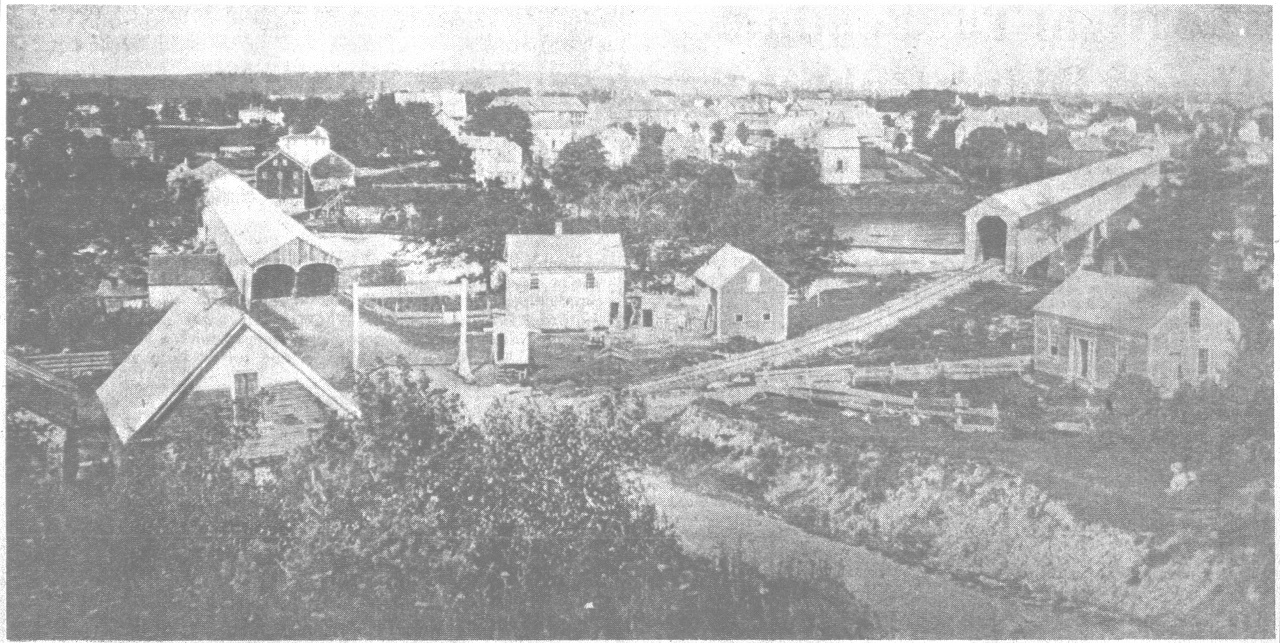

This photograph was taken from atop Sand Hill, in Winslow, looking towards Waterville. Taken in 1870, the photo shows the two covered bridges that carried trains (right), and wagons, back and forth between the two communities. The bridge on the left is the Ticonic Bridge that connects Waterville and Winslow, which today is a four-lane crossing. (photo courtesy of Waterville Historical Society)

Neither Kingsbury nor the Waterville bicentennial history mentions ferries in the 1700s. The first bridge linking Waterville and Winslow was built in 1823, Kingsbury says. Like the early Augusta bridges a covered toll bridge built by entrepreneurs, it lasted until a flood in 1832; its successor, another covered toll bridge, was washed downstream in 1869.

The county commissioners then ordered Waterville and Winslow to build a new bridge. It opened in 1870, toll-free; but Kingsbury says construction errors made rebuilding necessary within a few years. Its solid piers supported the iron bridge still in use in 1892.

In his account of the early days of the North Fairfield Friends (Quakers), Ernest Marriner (Kennebec Yesterday) describes their trips to the Vassalboro Friends meeting, crossing the Kennebec. There was no ferry service north of Augusta until around 1802, Marriner says, so when the water was low, people waded across; in high water, they used rafts.

The ford at Waterville was downstream of Ticonic Falls, Marriner says. He says a traveler started from the west bank slanting downstream, turned upstream to a small island and from the island went straight across to Winslow. Small round rocks on the river bottom provided poor footing for horses once the Friends had horses.

The history of Fairfield lists three ferries across the Kennebec, all north of what is now downtown, without dates. Ames’ Ferry was at Emery Brook, Noble’s Ferry was a quarter mile downriver from Nye’s Corner and Pishon’s Ferry was at Hinckley.

Fairfield and Benton were connected by bridges in 1848, three covered bridges going via the two islands, Mill (apparently known earlier as Oakes’ Rock and Rock Island) and Bunker’s Island. They were toll bridges until 1873, and when the Fairfield bicentennial history was published in 1988 the toll-house on the north end of Bunker’s Island was still standing; it was torn down not long afterward.

The history says until 1873, the town line ran down the center channel of the river, leaving Bunker’s Island and two bridges in Benton. Benton, reluctant to assume the expense, petitioned the state legislature to transfer Bunker’s Island to Fairfield. The petition was granted Feb. 27, 1873..

The history says the wooden bridge between Fairfield and Mill Island was replaced with a steel one in 1887. The islands must have been connected by a new steel bridge sometime in the next 11 years, because the history says an early-March 1896 flood washed away the remaining covered bridge between Bunker’s Island and Benton and a steel one was built there, too. In 1934 all three bridges were replaced, again with steel.

Next: The useful Kennebec: transportation, water power, etc.

Main sources:

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988)

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954)

Robbins, Alma Pierce History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Web sites, miscellaneous

State celebrates 200th anniversary on March 15

State celebrates 200th anniversary on March 15