Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Music in the Kennebec Valley – Part 5

by Mary Grow

Two musical Hallowell families

In the course of reading about the history of music in the central Kennebec Valley, specifically George Thornton Edwards’ 1928 Music and Musicians of Maine, your writer came across two intertwined musical families who lived in Hallowell, before and after Augusta became a separate town in 1897.

Both were from England. Edwards, James W. North (in his 1870 Augusta history) and Henry Kingsbury (in his 1892 Kennebec County history) paid attention to:

- Benjamin Vaughan, M.D., LL.D. (April 19, 1751 – Dec. 8, 1835), son of Samuel and Sarah (Hallowell) Vaughan;

- His younger brother, Charles Vaughan (June 30, 1759 – May 15, 1839); and

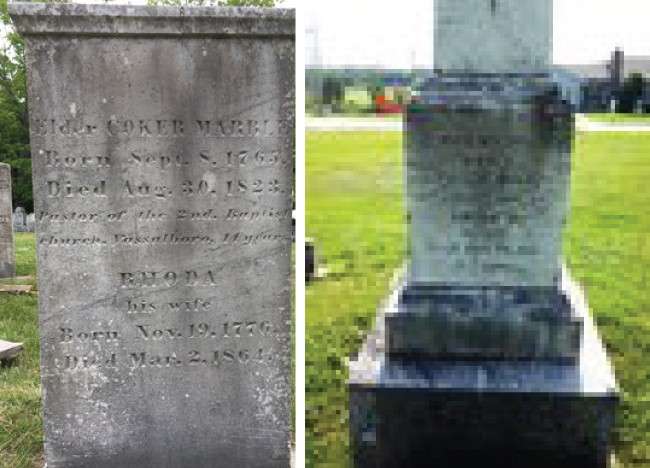

- John Merrick (April 27, 1766 – Oct. 22, 1861; or 1862), husband of Benjamin and Charles’ sister Rebecca (1766 – July 1851).

Benjamin Vaughan was born in Jamaica, educated in Britain (including Trinity Hall, one of the Cambridge colleges, from which he did not graduate) and earned his medical degree at the University of Edinburgh.

He was interested in science and politics, a combination, Wikipedia says, led to his friendship with Benjamin Franklin. He and his wife, Sarah (Manning) Vaughan (April 29, 1754 – 1834), whom he married in 1781, also knew other leading families in the new United States, including the Washingtons, Adamses and Jays.

Vaughan was a participant in the negotiations to end the American Revolution. In 1786, he was elected a member of the Philadelphia-based American Philosophical Society.

In 1792 Vaughan was elected a member of the British Parliament. But his politics were out of step – he had supported both the American Revolution and the 1789 French Revolution – and he left Britain for France in 1794. He moved on to Switzerland; in 1795 (probably; other sources say 1796 or 1797) to Boston; and a year or two later to the family property in Hallowell – Hallowell because the Vaughan brothers inherited land there from their mother’s family.

Here, according to the on-line Maine An Encyclopedia, Vaughan practiced medicine for the first time, serving the poor and “usually supplying medicines as well as advice without charge.” He helped manage the family land and advised other landowners.

Maine An Encyclopedia says that in Hallowell, “he built houses, mills, stores, a distillery, a brewery, and a printing-office, and established a seaport at Jones’s Eddy, near the mouth of the Kennebec.”

He brought with him a library, the same source says, almost as big as Harvard’s (2,000 books smaller, an on-line source says), and spent much time researching and writing articles on politics and science. Harvard gave him an honorary LL.D in 1807, Bowdoin in 1812.

In addition to Benjamin Vaughan’s many business activities, an on-line source says in 1820, the Maine legislature asked him to design a seal for the new state. He recommended the farmer and the mariner, symbols of work; the moose, for nature; the pine tree, for timber resources; and the north star overhead.

Charles Vaughan came to the family property in Hallowell a few years earlier than Benjamin, according to Edwards and others (but Kingsbury said a few years after Benjamin, whose arrival he put in 1796). One on-line source dates Charles’ arrival 1790, another “around 1791.” Sources call him a merchant instrumental in Hallowell’s economic development.

Benjamin and Sarah Vaughan had at least seven children. Charles and his wife, Frances Western Apworth or Apthorp (1766 – 1818, or Aug. 10, 1836, or May 15, 1839), had three or four children.

John Merrick (who often has “Esquire” after his name) was born in London; Edwards said he was “of Welsh origin.” North said he studied for the ministry, but did not pursue it. At some point he “became a tutor” in Benjamin Vaughan’s family, and when the Vaughans moved to America in the 1790s, he came with them.

In 1797, North wrote, he went back to London, where in April 1798 he married Rebecca Vaughan, bringing her to Hallowell in May. North listed six Merrick children.

North, who had known Merrick at least casually, and Edwards both speak highly of him as a man and a civic leader. North wrote that Merrick “was a gentleman of thorough education, refined tastes, high intellectual and social culture, benevolent, public spirited, kind, courteous, and gentle…just in all his dealings, of excellent judgment and practical good sense, a good citizen highly esteemed and beloved by his neighbors and friends….”

Describing Merrick in his 90s, showing a companion where a recent Kennebec River flood had cut around the Augusta dam, North wrote: “His form…was erect, his step elastic, and his flowing long locks of a snowy whiteness resting upon his shoulders gave him an imposing and venerable appearance.”

Edwards added that Merrick was well-informed about “astronomy, navigation, mathematics, and surveying.”

Among Merrick’s civic roles the two authors listed were trustee of Hallowell Academy (from 1802) and board president in 1829; member of Bowdoin College’s Board of Overseers (1805); Hallowell first selectman “for many years” (North) and overseer of the poor for 10 years; and cashier of the second Hallowell and Augusta Bank from 1812 until it failed in 1821.

In 1810, North wrote, Massachusetts Governor Christopher Gore appointed Merrick a member of an expedition charged with exploring a possible road from the Kennebec to Québec. During the six-week expedition, “he camped out twenty-one nights, seventeen of which it rained.”

Edwards devoted considerable attention to the musical side of the Vaughan and Merrick families. He summarized: “The Vaughans, the acknowledged leaders of all social events in Hallowell, were liberal patrons of the arts, and they and the Merricks were responsible in no small degree for the prestige which Hallowell was destined for nearly a century to enjoy as a musical center, and for the musical advancement of the towns along the Kennebec River.”

Music was important in both families, Edwards continued. Both sets of parents provided for their children the best available “instructors in piano, violin and flute.”

Merrick was one of the tutors in the Benjamin Vaughan family; their French teacher was a violinist. Charles and Frances Vaughan’s son, Charles, born in 1804, became a flutist and cellist; their daughter, Harriet, was a pianist and singer.

(Benjamin and Sarah Vaughan also had a daughter they named Harriet, the first-born of their seven children. Born in 1782, she died in 1798.)

Charles and Frances Vaughan’s daughter Harriet, born April 15, 1802, married children’s book author Jacob Abbott (Nov. 14, 1803 – Oct. 31, 1879) on May 18, 1829. Harriet Vaughan Abbott died Sept. 12, 1843.

Jacob and Harriet had several children. Another on-line source provides a brief biography of their oldest son, one of Charles Vaughan’s grandsons. He was Benjamin Vaughan Abbott, born in Boston June 4, 1830, a Harvard Law School graduate (1852). He is recognized primarily for his many collections and digests of court rulings and other legal records, work with which his brother, Austin Abbott, helped.

Merrick, in addition to tutoring Vaughan children, was a talented musician and leader. Edwards wrote that his musical taste was “exquisite.” He was known as a cellist, singer (Edwards quoted a description of his voice as “a very sweet and highly cultivated tenor”) and music critic. Linda Davenport, in her Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier, included a quotation saying Merrick “could play on any instrument.”

Locally, he led outstanding choirs at Hallowell’s Old South Church (called the best in New England in his time) and the Gardiner church, Edwards said. He also sang in the old South Church choir, as did Jacob Abbott.

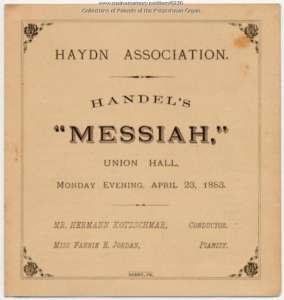

When the Handel Society of Maine was formed in Portland in February 1814, Merrick was its first president. Edwards described the group as an ambitious state-wide effort that probably lasted only a few years, holding twice-yearly meetings at Bowdoin College. Its short life he attributed to the many other demands on members’ time, their limited resources and the difficulty of travel in Maine in the early 1800s.

Edwards listed one more of Merrick’s musical accomplishments: he wrote that when Samuel Tenney published The Hallowell Collection of Sacred Music in 1817 (second edition 1824), Merrick and (future) Chief Justice Prentiss Mellen, from Biddeford, “two of the ablest men in the state,” assisted.

Davenport analyzed the history of The Hallowell Collection in more detail, pointing out that although it is attributed to Samuel Tenney, he is not named “on the title page, in the notice about the copyright deposit, or in the introductory advertisement.”

Merrick and Mellen did endorse the collection, Davenport said, in their capacities as president and vice-president of the Handel Society. She disagreed with the suggestion that the Society published the book.

In Davenport’s opinion, “A more likely possibility is that Merrick and possibly Mellen may have served as musical advisors to the book’s publisher, Ezekiel Goodale, a Hallowell printer who was not known to have been musical.”

Merrick, because of his education and his experience leading choirs, she believed probably guided the choice of mostly-European music and wrote the “theoretical introduction, portions of which are more detailed and erudite” than in other contemporary collections.

Mellen could have contributed from Biddeford. Tenney might have helped, Davenport wrote, and almost certainly used the book when he opened his singing school for sacred music late in 1817.

Main sources

Davenport, Linda, Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier Maine’s Sacred Tunebooks, 1800-1830 (1996).

Edwards, George Thornton, Music and Musicians of Maine (1928).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).