Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Palermo

by Mary Grow

Palermo is the only town in this series that is not in Kennebec County. The boundary line between China on the west and Palermo on the east is also the line between Kennebec and Waldo counties. It runs through Branch Mills, formerly Palermo’s main commercial center.

It is not Palermo residents’ fault that they don’t live in Kennebec County. In 1760, all of Maine was organized as Lincoln County; divisions since then have created the present 16 counties. In 1789, part of Lincoln County, not including current Palermo, became Hancock County. On Feb. 7, 1827, Waldo County was created from parts of Hancock and Lincoln counties and included Palermo.

On Feb. 23, 1827, historian Millard Howard says in An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine, (second edition, December 2015), Palermo voters unanimously asked the legislature to add them to Kennebec County. Their request was not granted.

Nor is Palermo part of the Kennebec River watershed. Instead, the town is doubly in the Sheeepscot River basin. Branch Pond and Branch Mills, on the western edge of the town, are on the West Branch of the Sheepscot, and Sheepscot Pond, which fills about a third of the southern half of Palermo, is on the main stem. The two rivers join well south of town, between Coopers Mills and North Whitefield.

A multitude of small ponds are scattered through northern Palermo; not all have names on the contemporary Google map. Named ponds include, in a northern tier and moving from east to west, Prescott, Nutter and Chisholm.

The next tier south, approximately east of Branch Pond, includes, from east to west, Bowler, Foster and Belden. South of them are Dowe Pond on the east, not far from Branch Mills; Saban Pond and to its south Bear Pond, about mid-way between the eastern and western boundaries; and Jump Pond, south of Foster Pond.

Beech Pond, near Greeley’s Corner (or Greely Corner, or Center Palermo) between Parmenter and Cain Hill roads, is the final named pond north of Route 3. South of the highway, Sheepscot Pond has a tiny nameless blue spot on the map to its northwest; Turner Pond, shared with Somerville, on its southwest; and on the southeast another blue spot identified as Deadwater Slough.

According to Howard, Stephen Belden, his wife Abigail and their son Aaron were Palermo’s first settlers, in 1769. Their second son, Stephen, Jr., was born in 1770, the first settlers’ child born in Palermo.

The Beldens chose not to homestead beside Sheepscot Great Pond, as Sheepscot Pond was then called. Howard suggests they chose a more secluded location because they were squatters with no legal title to the land and did not want visits from agents of the Kennebec Proprietors, owners of a large tract 15 miles on either side of the Kennebec River.

Howard locates the first Belden homestead only by late 20th century owners Robert and Susie Potter. Later, he said, the Beldens moved to the shore of what was then Belden, and later became Bowler, Pond.

Other people who arrived in the 1700s, according to Howard (who did a great deal of research in early documents) were Hollis Hutchins (1775), who, Howard says, settled “in the lower Turner Ridge area”; Jacob Greeley, Jr, (1777) and John Foye (1778), near Beech Pond; and Jonathan Bartlett (1788), who built the first sawmill on the Sheepscot south of Sheepscot Great Pond.

Other early names Howard mentions include Albee, Boynton, Bradstreet, Cressey, Lewis, Turner and Worthing. Ava Harriet Chadbourne’s Maine Place Names and the Peopling of Its Towns (1955) adds Bowler, Clay, Longfellow and Waters in the 1770s and 1780s. Many settlers had large families who intermarried through the generations. For example, Howard says Hollis Hutchins’ five sisters married into the Albee, Boynton, Cressey, Foye and Turner families.

The area was first called Sheepscot Great Pond Settlement. After an 1801 survey of 27,100 acres by William Davis of nearby Davistown (now Montville), it was organized as Sheepscot Great Pond Plantation. Howard says the first clerk of the plantation was a well-liked 24-year-old doctor from Vermont named Enoch P. Huntoon.

Immediately after the plantation was created, 55 residents asked the Massachusetts General Court to make it a town and to name it Lisbon. The requested name, Chadbourne and Howard explain, was part of a trend to name Maine towns after important foreign places – hence the famous Maine road sign that lists seven foreign countries honored in Maine plus Naples and Paris (but omits Belgrade, Lisbon, Palermo, Madrid, Rome, Sorrento and Verona Island).

The Lisbon on the sign is the Androscoggin County Lisbon between Lewiston and Brunswick, not the one requested in Waldo County. Lisbon was settled in 1628, its website says, and incorporated as Thompsonborough in June 1799. In December 1801 residents asked the Massachusetts legislators to

change the name to something less cumbersome, suggesting Lisbon. On Feb. 20, 1802 (after Sheepscot Great Pond’s petition was filed but before the legislature acted) Thompsonborough became Lisbon.

Sheepscot voters looked for another capital. They also realized that the P. in Dr. Huntoon’s name stood for Palermo. On June 23, 1804, the Massachusetts General Court approved the incorporation of the town of Palermo. Howard wonders if local residents realized Palermo in Sicily had been an important medieval center and, in his opinion, was a better choice than Lisbon.

Early transportation in Palermo was by the Sheepscot River and by trails. One of the functions of a town government was to lay out, build and maintain roads; Howard says Palermo officials were especially active from 1805 until about 1820. The first road linking the southern settlements with northern Palermo followed a route approximated by the present Turner Ridge Road (which joins Route 3 from the south at Greeley’s Corner, east of Beech Pond); Parmenter Road (which goes north off Route 3 west of Beech Pond); and Marden Hill Road (Parmenter Road’s name north of the four-way junction with Nelson Road and Belden Road). Marden Hill Road continues northeast to connect with North Palermo Road.

The southern end of town gradually lost importance. By the 1820s, Howard mentions five centers along or north of present Route 3: Branch Mills; Greeley’s Corner; Carr’s Corner on the North Palermo Road west of Prescott Pond; Ford’s Corner, where the North Palermo and Chisholm Pond roads meet; and East Palermo, the junction of Banton Road and Route 3.

A “center” would have at least one public building and/or business and a cluster of houses. The public building might be a post office; at various times, Branch Mills, Center Palermo, North Palermo and East Palermo had one. In the 1860s, Howard says, Greeley’s and Carr’s corners each had at least one store, at least one church and a school.

Howard found that Palermo reached its greatest growth in terms of population around 1850. He cites a series of census figures: 1790, 164 people counted; 1800, an almost threefold increase to 444; 1820, 1,056, the first count over 1,000; 1840, 1,594; 1850, the highest recorded, 1,659. A gradual decline began with a loss of almost 300 by 1860. By 1890, the population was again below 1,000, at 887. Howard’s list stops at 1950, when the population was recorded as 511. A steady increase began in 1970, and the 2010 census recorded 1,535 inhabitants, almost back to the pre-Civil War high.

The 1886 Gazetteer of the State of Maine says Branch Mills was then the largest village, with eight mills. Center Palermo had a “board and shingle-mill” and a stone quarry; East Palermo had two lumber mills; and North Palermo had a factory that made drag-rakes.

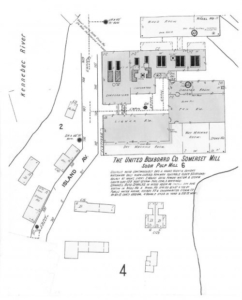

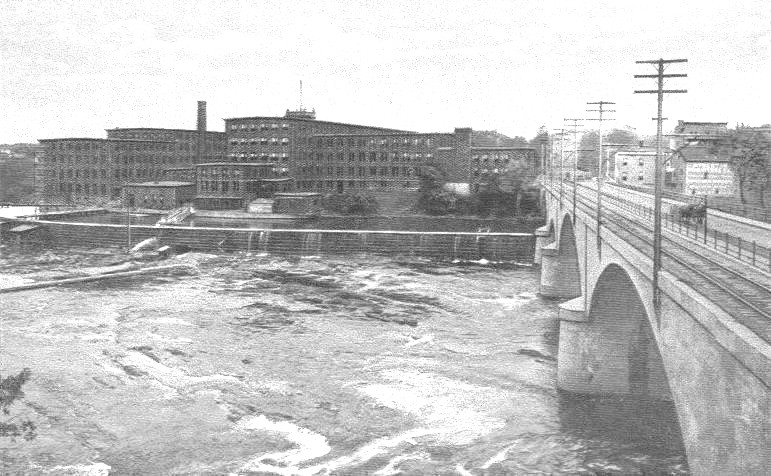

One of the mills in Branch Mills was the Dinsmore Grain Company Mill, on the China side of town. The mill building and its associated dam stretched across the Sheepscot River, with access to the building from the east shore.

The first mill on the site was built in 1817 by Joseph Hacker, according to a Wikipedia article. Hacker’s son-in-law, Jose Greely, succeeded him, and in 1879 Greely took his son-in-law, Thomas Dinsmore, as a partner. Thomas Dinsmore’s son James Roscoe Bowler Dinsmore succeeded him.

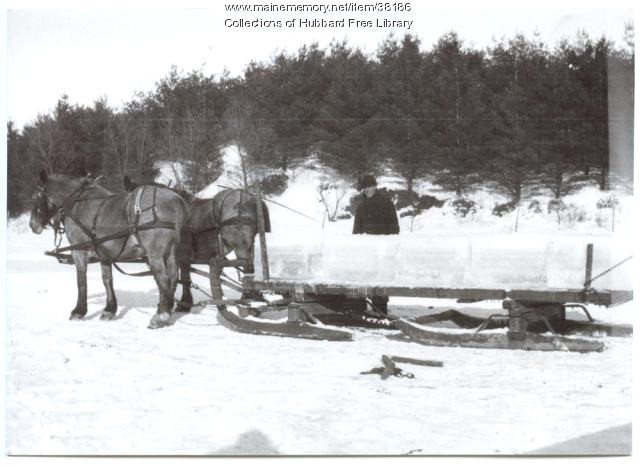

The 1908 fire that destroyed most of Branch Mills destroyed the mill as well. James R. B. Dinsmore rebuilt it in 1914 as a two-and-a-half-story wooden building, shingled, with a three-story tower on the south side. Initially it was only a grist mill, in 1935 James Kenneth Dinsmore (James R. B. Dinsmore’s son) added a sawmill operation, which continued until 1960.

On Nov. 3, 1979, the Dinsmore mill was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Subsequent owners proposed reusing it, but none succeeded. Both the building and the dam deteriorated, to the point where waterfront property owners on upstream Branch Pond complained that the dam no longer kept water levels high enough for recreation. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection also objected that its water level regime for Branch Pond was violated.

By 2016, the mill owners claimed the building was too dangerous to repair. In 2017, the Atlantic Salmon Federation acquired the property, tore down the historic building and negotiated with state regulators to add a fishway for salmon and other anadromous fish to the dam.

Main sources

Howard, Millard An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015)

Web sites, miscellaneous

Note: Milton E. Dowe’s highly recommended History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 was published in 1954. Unfortunately, with libraries closed it was not available to this writer in time to be studied.

Most information in this section is from the comprehensive history section of

Most information in this section is from the comprehensive history section of