Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Augusta families – Part 4

by Mary Grow

Henry Sewall, part one

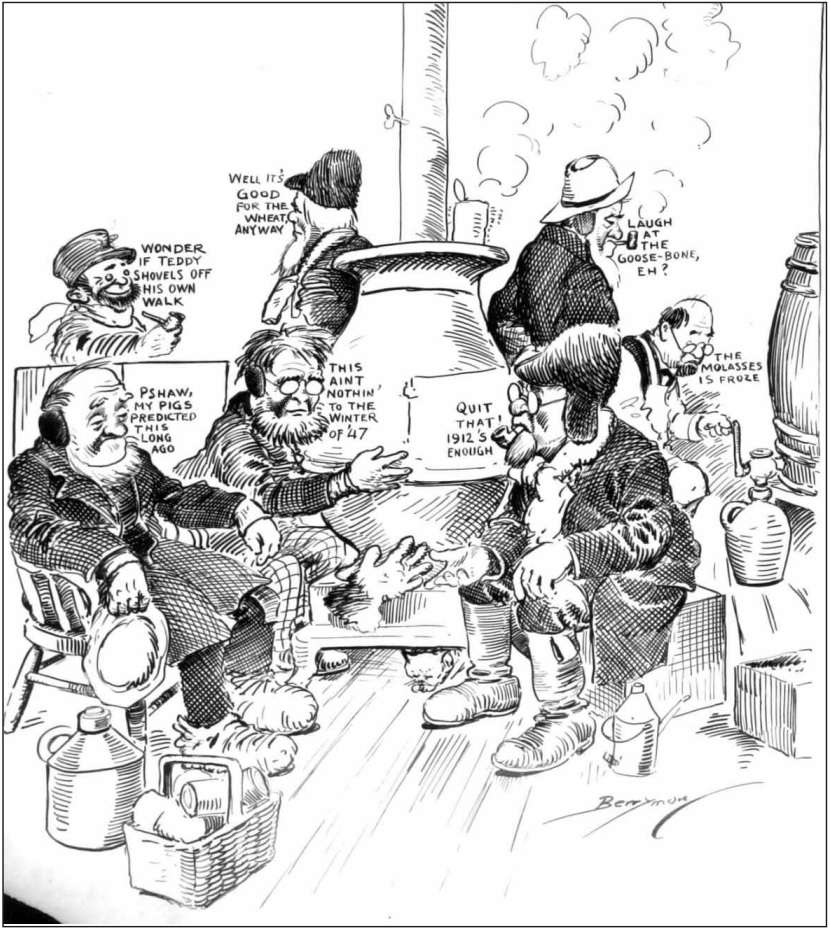

The fourth early Augusta settler, prominent citizen and diarist your writer promised to introduce was Henry Sewall (Oct. 24, 1752 – Sept. 4, 1845).

His diary poses a puzzle. James North, whose history of Augusta was published in 1870, relied heavily on it from the 1780s through the late 1790s, and mentioned it in footnotes to events in 1820 and 1828, but not thereafter. Charles Nash, in his Augusta history published in 1904, wrote that from the end of Sept. 1783 to 1830, “the MS of Capt. Sewall’s Diary is missing.” Nash excerpted entries for 1783 and from 1830 to Jan. 31, 1843.

Diary entries are brief. Sewall recorded the weather; church-related events; and local deaths and funerals, including many in his own family. He often mentioned a town meeting or beginning of a legislative session, but said little about their outcomes.

Thanks mostly to the diary, Sewall’s life is well enough documented to provide material for two articles in this series. They will be followed by one more story on central Kennebec Valley towns planned for March 16; then your writer intends to take a break at least until the end of April.

* * * * * *

Some sources call Henry Sewall Captain Sewall, others call him General Sewall, and he is entitled to both ranks.

He was born in York, Maine, son of Henry and Abigail (Titcomb) Sewall. His father was a farmer and a mason, and he followed both occupations.

At the beginning of the Revolution, North wrote, Sewall enlisted in a Falmouth company that in May 1775 joined a Massachusetts regiment. He was promoted to captain as the regiment fought in New England and New York before British General John Burgoyne’s army surrendered at Saratoga on Oct. 17, 1777.

In November, North said, the Massachusetts soldiers joined the Continental Army in Pennsylvania. Sewall spent the winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge; he “served the remainder of the war in New Jersey and the highlands of New York.”

North and an on-line article by a Sewall descendant agree that Sewall became a major, maybe as of May 19, 1779. His military service earned him a government pension; by the 1830s, he was recording in his diary semi-annual payments of $240.

The on-line source says Sewall was an “Original Member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati from 1783 until 1845,” and in 1845 (the year of his death) its vice-president. In 1836, he described in his diary the week-long trip he and his wife took to the society’s annual meeting in Boston. They went again in July 1838, and this time, at his wife’s urging, had their portraits painted by “Mr. Badger” (Thomas Badger, 1792-1868).

(The Society of the Cincinnati, which one source calls “the nation’s oldest patriotic organization,” was founded by Revolutionary officers and is named for Roman general Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus [c. 519 – c. 430 BC]. It is now a nonprofit educational association headquartered in Washington, D.C.

(The society’s website says members are male descendants of Revolutionary War officers [former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill became a member in 1947], but anyone sharing an interest in promoting “the understanding and appreciation of the American Revolution and its legacy” can be an associate member.)

Your writer found two stories from Sewall’s later life harking back to his army days.

North wrote that when the Marquis de Lafayette (the French general famous for his help to the Americans during the Revolution) visited Portland in 1825, Sewall, who had known him well, was in the crowd honoring him, but held back. Lafayette “saw and recognized him and perceiving his design exclaimed, ‘Ah! Henry Sewall you can’t cheat me.’ They embraced, and the aged soldiers wept.”

In the spring of 1839, U. S. General Winfield Scott passed through Augusta on his way to and from Aroostook County, where border troubles with Canada had flared up. Scott, born in 1786, had never soldiered with Sewall. Nonetheless, on March 27, as Scott returned south, Sewall wrote one sentence in his diary: “General Scott called on me.”

Sewall’s generalship was as Major-General in the Maine militia, Eighth Division, in which he served from 1790 to 1820. The division included men from Lincoln County and later Kennebec (established Feb. 20, 1799) and Somerset (established March 1, 1809) counties.

North wrote that Sewall moved from York to Hallowell in September 1783. Except for a brief unsuccessful attempt to start a business in New York in 1788-89, the central Kennebec Valley was his home for the rest of his life.

Other Sewall men who came from southern Maine to the Kennebec were Henry’s brother Jotham, who had a “plantation” in Chesterville but was often in Hallowell; David and his brother Moses; and Thomas, Henry’s cousin and close friend (born Sept. 24, 1750, came to Hallowell in 1775, died May 4, 1833).

There were other Sewalls on the coast in and around Bath and Georgetown. Sewall’s diary entries from 1783 mentioned uncles named as D., Dr., Dummer and Joseph; a sister married to a man named Parsons; and a cousin named Samuel. North added a David Sewall, who visited Hallowell at least once.

A short series of diary entries from late August 1783 describes typical family connections. After dinner with Uncle Joseph at Arrowsic on Aug. 27, Sewall wrote that he and Jotham, whom he met at Dr. Sewall’s, canoed upriver to Hallowell and spent a night at cousin Thomas’s.

On Aug. 29, “Helped my brother build T. Sewall’s chimneys.”

And on Sept. 1, “Helped my brother lay out a cellar at Hallowell….”

Besides working as a mason, Sewall, with a partner named William Burley, ran a store on the east side of the Kennebec for about five years, starting in late 1783.

In the spring of 1784, Henry and Thomas Sewall and Elias Craig (previously mentioned in several 2022 articles about Augusta) built what North called a “great canoe.” Using Sewall’s diary as his source, North described some of its uses; for instance, in early July Henry, Jotham and their cousin Tabitha Sewall (see below) from Georgetown went downriver to Bath on a Saturday and to Georgetown for church on Sunday.

Henry’s horse was at Georgetown, so when the wind was against them Monday he rode back upriver, leaving Jotham to bring the “canoe” – and presumably Tabitha – back later.

Sewall’s first involvement in official town business seems to have been in 1785, when Hallowell voters chose him, newly elected town clerk Daniel Cony and Joseph North to petition the Massachusetts Court of Sessions for a new road.

On Feb. 9, 1786, at Georgetown, he married his first wife, his cousin Tabitha (Thomas’s younger sister, born on or before Nov. 25, 1753, died June 19, 1810). North said they had two sons and five daughters. Other sources give varying numbers.

Henry Sewall’s son Charles (Nov. 13, 1790 – June 28, 1872) had a son named Henry, born Dec. 3, 1822, who was a “lieutenant and adjutant” in the 19th Maine Regiment in the Civil War. This second Kennebec Valley Henry Sewall named his sons Harry (born July 4, 1848) and Charles (born July 5, 1861).

After Tabitha’s death, North wrote that on June 3, 1811, in Salem, Massachusetts, Sewall married another cousin named Rachel Crosby (Dec. 12, 1754 – June 15, 1832). On Sept. 9, 1833, he was married for the third time, to Elizabeth Lowell (Oct. 6, 1777 – March 13, 1861), in Augusta, with Rev. Benjamin Tappan performing the ceremony.

* * * * * *

In 1789, North wrote, Sewall came back from his venture in New York City on Sept. 12, and the next month went to Boston “to see President Washington,” who was there on Oct. 24, and was in a parade of ex-army officers.

In Boston he crossed paths again with David Sewall, newly-appointed “judge of the District Court of the United States for the Maine District.” David Sewall chose Henry Sewall as the court clerk, a post he held until 1818.

District Court was held in Portland, and North wrote that until 1794, Sewall’s trip on horseback from Hallowell took almost two days, via Bath. By June 1793 enough new roads had been built so that he could go by way of Monmouth; if he started early enough to have breakfast in Monmouth (about 20 miles on his way), he could be in Portland fairly early the next morning, North wrote.

By June 1800, he had a third choice, through Brunswick, still requiring an overnight stop.

He became Hallowell town clerk in 1789, North wrote, was re-elected at Harrington’s first town meeting in April 1797 and continued in Augusta, for a total of 32 years. Nash, in his chapters on Augusta in Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, listed his terms as 1797-1801, 1806-1815 and 1818-1829.

When Hallowell’s first court house was built in 1790, North wrote that Sewall contributed $10 “in labor and materials,” and “built the chimneys,” with his brother Jotham helping intermittently. He also helped build Hallowell’s meeting house, started in 1782 and used for both civic and religious assemblies.

Sewall was briefly a Hallowell selectman; North mentioned him in the position in June 1791. After Augusta became a town, Nash wrote that he was elected selectman in 1798 and served two years.

According to North, Sewall was not heavily involved in discussions of Maine statehood, nor was he active in the debates leading to the division of Augusta from Hallowell in February 1797.

When Kennebec County was separated from Lincoln County in February 1799, Sewall was its first register of deeds, North wrote. He held the post until April 1816.

Augusta residents did not learn of George Washington’s Dec. 14, 1799, death until Jan. 1, 1800, North wrote (quoting Sewall’s diary). A Feb. 6 town meeting appointed a committee, including Sewall, to plan a suitable observance on Feb. 22. More than 1,000 area residents attended.

As a militia officer, Sewall was on alert much of the time in the early 1800s. During the settlers’ insurrection that culminated in open violence in 1808, he (and Daniel Cony, as mentioned last week) were part of the volunteer patrol in Augusta. On Jan. 19, county sheriff Arthur Lithgow asked for 400 militiamen to resist the “insurgents,” and Sewall held them ready until Massachusetts Governor James Sullivan overruled Lithgow on Feb. 2.

When the jail in Augusta caught fire on March 16, 1808 (see the Oct. 27, 2022, issue of The Town Line), Sewall was again asked for help. Court of Common Pleas judges Joseph North and Daniel Cony requested soldiers to protect the court house and to prevent jail inmates from escaping from the nearby private house to which they had been moved.

Sewall “ordered the Augusta Light Infantry upon duty; and they continued under arms during the night.”

The arrest and incarceration in Augusta of a band of settlers who had killed a surveyor named Paul Chadwick led to a more serious episode during the first full week of October 1809.

As North told the story, an armed group of 70 or so men planned a jailbreak; they reached the Augusta bridge around midnight Oct. 3, were spotted, and by 1 a.m. Oct. 4 the new sheriff, John Chandler, again had Sewall calling out the militia. This time neighboring towns’ units were included, cannon guarded the bridge and a gun from the Hallowell artillery company “was planted so as to command the entrance to the jail.”

North wrote that when Sewall reported what he had done to Massachusetts Governor Christopher Gore, the governor’s Oct. 14 ordered commended his “promptitude and alacrity.” After a week on full alert, precautions were gradually relaxed.

The Sept. 11, 1814, report of an impending British landing at Wiscasset again led Sewall to dispatch troops. North wrote that he got notice while in church, immediately ordered two regiments plus the Hallowell artillery company to the coast and on Sept. 15 went himself and took charge.

As described previously (see the Feb. 17, 2022, issue of The Town Line), there was no landing.

After Augusta became the state capital, Sewall commented in his diary for 1830 on the progress on the new State House: the pillars “began to be raised” Oct. 21 and were “all up” on the 25th. On Dec. 11 he wrote that the outside of the building was done “except the dome.”

On Oct. 24, 1832, Sewall wrote: “My birthday – 80 years old! My friends and my companion gone! [His second wife, Rachel, had died June 15, after being unwell since the beginning of the year.] Can I expect to stay?” Then, as he often did on his birthday, he quoted poetry:

“Still has my life new wonders seen, repeated every year;

The scanty days that yet remain, I trust them to thy care.”

Henry Sewall died Sept. 4, 1845, and is buried in Augusta’s Mount Vernon Cemetery, with his third wife and four descendants.

Next week: Henry Sewall’s religion

Main sources:

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.