Trotting park.

Your writer intended to deliver the promised article on Charles Hathaway and his shirt company, and more information on Waterville’s historic Main Street buildings, this week. But a reader reacted to last week’s digression on agricultural fairs with a question: what is a trotting park?

Hence another digression, which led your writer to a delightfully illustrated, highly recommended website: The Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center (see box). This page will share some of the information from this and other sources.

Disclaimer: your writer is not a horse expert. Readers who are, please be kind.

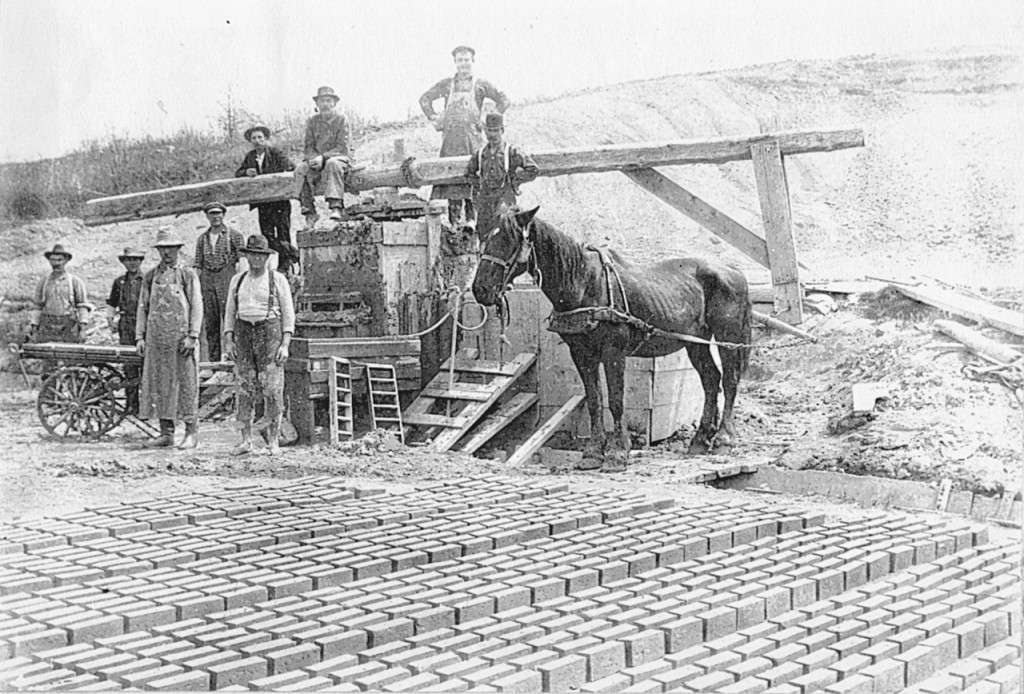

A trotting park, also called a harness racing track, is an oval dirt racetrack, usually a mile long but sometimes shorter. Historically, a trotting park could be public, owned and maintained by an agricultural society of other organization, or privately owned.

On these tracks trotting or pacing horses race, each pulling a sulky with a single human occupant.

Wikipedia says most horses have four “natural” gaits, or “patterns of leg movements.” In order from slowest to fastest, they are called walk, trot, canter and gallop.

The Wikipedia writers describe the gaits in terms of two, three or four “beats.” The trot is a two-beat gait; the horse lifts left front and right rear hoofs simultaneously, then right front and left rear. Average speed is a bit over eight miles an hour.

Wikipedia’s illustrations include a photo of Thomas Eakins’ painting from 1879 or 1880 titled The Fairman Rogers Four-in-hand, or A May Morning in the Park. It shows a group of people in a coach drawn by four brown horses, the two lead horses clearly trotting.

The trot is a comfortable gait that a horse can maintain for hours, Wikipedia says. It is less comfortable for a human rider, who is bounced up and down; riders therefore learn to “post,” to raise themselves up and down in the stirrups in time with the horse’s motion.

The pace, called on another site an artificial gait, is also a two-beat gait, but the two legs on the same side of the horse’s body move together, so that the horse rocks from side to side – even less comfortable for a rider than trotting.

Harness racing could be for either trotters or pacers, Wikipedia says. In the United States, harness-racing horses must be Standardbred. Wikipedia says Standardbreds have shorter legs, longer bodies and “more placid dispositions” than Thoroughbreds.

A sulky, also called a bike, a gig or a spider, is a light-weight, single-seat horse-drawn vehicle with two large wheels.

On-line sites indicate that harness racing is common worldwide. In the United States, there are races for both pacers and trotters. A pacer or trotter who comes in top in each of three sets of races in the same year becomes a Triple Crown winner.

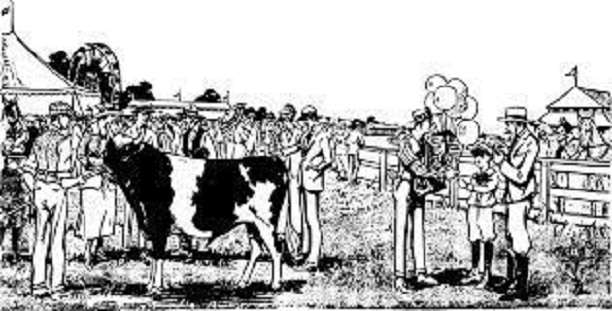

This year’s Windsor Fair program included harness racing. The Windsor Historical Society, headquartered on the fairgrounds, has information and photographs about past horses and races.

* * * * * *

Last week’s story mentioned trotting parks in China, Waterville and Windsor. Henry Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that China’s, Windsor’s and one of Waterville’s were public. China’s was built in 1868 and abandoned before 1892.

Kingsbury listed six nineteenth-century private parks in the county. Four were still operating in 1892, one in Farmingdale, one in West Gardiner, and two in Waterville, C. H. Nelson’s and Appleton Webb’s.

Palermo native and Civil War veteran Charles Horace “Hod” Nelson (1843 – 1915), of Sunnyside Farm, in Waterville, was an internationally recognized horse breeder; his champion trotter, Nelson (1882 – Dec. 4, 1909) set multiple records and in 1994 was named an Immortal in the Harness Racing Hall of Fame.

Your writer failed to find information on an Appleton Webb she is sure was a trotting park owner. Waterville lawyer and politician Edmund Webb’s son Appleton (Aug. 12, 1861 – Aug. 23, 1911) would have been about the right age; one website says he was admitted to the bar, and none links him with horses.

Other trotting parks in the central Kennebec Valley included one in Albion, three in Augusta (two private) and one in Fairfield (apparently private).

* * * * * *

Albion’s trotting park, according to Ruby Crosby Wiggin’s history, was in Puddle Dock, a locality in the southern part of town on Fifteen Mile Stream. The South Freedom Road crosses the stream there; near the bridge, a dam provided water power for various small industries for years, and Wiggin found the South Albion post office was nearby from 1857 (or maybe earlier) to about 1890.

The 1857 postmaster, she wrote, was D. B. Fuller, who lived “in Puddle Dock just opposite Maple Grove Cemetery and on the same side of the road as the trotting park.”

Maple Grove Cemetery is on the southwest side of South Freedom Road, just north of its eastward turn to cross Fifteen Mile Stream; so the trotting park would have been on the northeast side, between the road and the stream.

Wiggin continued her history of fairs in Albion, summarized last week, by saying that after the records she found ended in 1891, the fairs probably wound down, becoming “mostly horse pulling and a horse trot…held at the Trotting Park at Puddle Dock, just opposite Maple Grove Cemetery.”

To many 1960s Albion residents, she wrote, the park was “the place where they learned to drive their first car.” Not long before her history was published in 1964, the park was converted to a large plowed field (visible in an on-line aerial view).

* * * * * *

Augusta’s principal trotting park appears on old maps on the west bank of the Kennebec River, just south of Capitol Park. Newer maps show the area housing the Augusta police department and the YMCA building and grounds.

An on-line site shows a postcard with the typical oval track. Accompanying text says the trotting park was on a 22-acre lot.

Both James North, in his 1870 history of Augusta, and Kingsbury said the park opened in 1858. That year, North wrote, the State Agricultural Society chose Augusta as the site for its fourth fair. City officials and workers spent the summer getting ready.

North wrote, “A trotting park was graded and fenced at considerable expense, on the ‘Bowman lot,’ adjoining the State grounds, where the fair was opened Tuesday, September 21st.”

The 1858 fair was the Society’s most successful thus far, North said, with more and better livestock than ever before shown in Maine and a fine display of industrial and agricultural products in a 50-by-84-foot wooden addition to the State House. During “the ladies’ equestrian exhibition,” attendance was estimated at up to 15,000 people.

On Thursday evening, North wrote, the fair hosted a guest speaker on agriculture, United States Senator Jefferson Davis from Mississippi. Some auditors praised his agricultural knowledge; others detected a political message. North wrote that the Kennebec Journal called the speech “a bid for the presidency, with an agricultural collar and wristbands.”

Kingsbury wrote that up to 1892, the Augusta trotting park operated “with but few intermissions” under successive owners; in 1892, it was run by the Capital Driving Park Association. At some point, the postcard caption said, grandstands with space for 2,000 spectators were built.

In addition to racing and fairs, the park hosted circuses; and in 1911, the on-line site says, it was the landing place for the first airplane to visit Augusta, described as “St. Croix Johnstone’s Moisant monoplane.”

(Your writer could not resist exploring these names on line. She found that John Bevins Moisant [April 25, 1868 – Dec. 31, 1910] was an American aviator from Illinois who designed the Moisant biplane, which crashed on its first flight in February 1910, and the Moisant monoplane, which Wikipedia says “had difficulty staying upright on the ground and was never flown.” A different article says St. Croix Johnstone [another Illinoisan, born Jan, 2, 1887, and died Aug. 15, 1911] “flew a Moisant monoplane,” described as a United States version of the 1909 French Bleriot XI. Both aviators died in flying accidents.)

The Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center website says Augusta’s two private trotting parks were on the east side of the Kennebec. George M. Robinson’s, built in 1872, was on South Belfast Avenue (Route 105). Alan (in other sources, Allen) Lambard’s, dating from 1873, was off Route 17. Kingsbury said both were “abandoned” by 1892.

North provided a short biography of Allen Lambard (July 22, 1796 – Sept. 5, 1877). He was by 1870 “in the evening of his days,” but still vigorous and interested in agriculture. His business ventures in Augusta and in Sacramento, California, had made him “the largest individual tax-payer in Augusta.” In October 1870, North wrote, he donated the house at the intersection of Winthrop and Pleasant streets as St. Mark’s Home for Aged and Indigent Women. The institution closed in October 1914.

The on-line Find a Grave site says Allen Lambard is buried in Augusta’s Forest Grove Cemetery. Other sources say Lambard was a grandson of Hallowell midwife Martha Ballard, made famous by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s publication of her diary.

George M. Robinson might be the man found on line who was born in 1823, died in 1888, and is buried in Augusta’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery; and might also be the man who made the March 25, 1876, Portland Daily Press after a gale blew down two of his barns.

* * * * * *

The Fairfield trotting park was located on the west side of town, west of West Street and south of the present Lawrence High School athletic fields. The Fairfield bicentennial history leaves its dates uncertain – it might have existed before 1872, while Fairfield was still called Kendall’s Mills, and it was very popular in the 1890s.

The local historians relied on two sources. One was a 1939 article by G. H. Hatch, who believed Edward Jones Lawrence (Jan. 1, 1833 – November 1918) and Amos Gerald (Sept. 12, 1841 – 1913) built the track “which was active in racing circles for years.”

Lawrence and Gerald owned and bred horses, according to Hatch. The first “really famous” Fairfield horseman, he said, was J. H. Gilbreth, whose horse named Gilbreth Knox was “a famous trotter of his day.” Gilbreth Knox is listed on line as a sire in the 1870s.

Lawrence acquired “the beautiful Knox stallion, Dr. Franklin,” listed as a sire in the 1880s.

The other mention of the trotting park in the Fairfield history tells readers that on Wednesday, Aug. 21, 1895, there was a “big event” at the trotting park that brought horses and people from miles around. The owners of the lumber mills in the downtown complex on the Kennebec River gave their employees the afternoon off to attend.

That day, for the third time, a fire started in a mill (earlier fires were in 1853 and 1882) and spread through the others. After the destruction, only one mill was partly rebuilt, and it didn’t last long. “Thus,” wrote the Fairfield historians, “the lumber industry in the Kendall’s Mills area of Fairfield, after a century of progress, came essentially to a close.”

The Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center

The Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center is a nonprofit organization in Hallowell, founded and run by Stephen Thompson. Its website describes its mission:

“to preserve the stories and images of the 19th century to present day that illustrate the history of Maine’s harness racing, lost trotting parks, fairs, agricultural societies, Granges, and the significance of the horse in society.”

A Kennebec Journal article from October 2021 says Thompson was looking for a space to turn his on-line venture into a physical museum.

Tax-deductible contributions are welcome. The website is losttrottingparks.com; the postal service address is Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center, P.O. Box 263, Hallowell, ME 04347; and Thompson’s email is listed as lifework50@gmail.com.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

This September, staff at Lovejoy Health Center welcome two new members: Nancy Johnson, Connector; and Hattie Blye, Care Manager.

This September, staff at Lovejoy Health Center welcome two new members: Nancy Johnson, Connector; and Hattie Blye, Care Manager.

To the editor:

To the editor: