Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Cony Flat Iron Building

by Mary Grow

One more former school in the central Kennebec Valley is on the National Register of Historic Places: the original Cony High School, in Augusta, often referred to as Old Cony High School, to avoid confusion with present-day Cony High School, or as Cony Flatiron, for its unusual shape.

Kirk Mohney of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission prepared the National Register application for the building in July1988. The listing is dated Sept. 29, 1988.

The Cony Flatiron is on a 1.5-acre lot, Mohney wrote, on the southeast side of Cony Circle, the traffic circle at the east end of Memorial Bridge across the Kennebec River.

The name comes from the building’s unusual wedge, or flatiron, shape. The slightly curved end with the entrance faces northwest onto the rotary; the sides flare out, so that the building is wider at the back.

High school education has been available in Augusta since 1816. Augusta’s on-line Museum in the Streets says in 1815, Daniel Cony put up a building on his land at the intersection of Bangor and Cony streets, on the northeast side of the present traffic circle. “At first a mystery, it was soon announced to be an academy for girls”; it opened as Cony Female Academy the next year.

The Museum in the Streets says in 1844 the Academy, needing more space, relocated across Cony Street into the former Bethlehem (Unitarian) Church building. The new site was the Flatiron Building lot.

Cony Female Academy closed in 1857. Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, and Mohney summarized information on other post-primary Augusta schools between the 1830s and the 1880s, apparently located on the west side of the Kennebec.

By 1880 the newest of these schools was overcrowded. Kingsbury wrote that Cony’s grandson, ex-Governor Joseph Williams, proposed that the still-existing Academy Board of Trustees give the school’s trust fund, which by then had grown to almost $20,000, to the city for a new high school.

Augusta officials accepted and built “the present [in 1892] stately edifice” as Cony Free High School on the Flatiron site. The building pictured in Kingsbury’s history resembles a church, with peaked roofs, an arched entrance and a tall, decorated central tower.

Museum in the Streets says the city “controlled the property” by 1908. In 1909 the Cony Free High School building acquired “substantial wings” (Mohney’s words), but by the 1920s it, too, had become too small, and officials replaced it with the Flatiron Building and renamed it Cony High School.

Mohney’s description of the Flatiron said the Colonial Revival style brick building was designed by Bunker and Savage, of Augusta, and constructed between 1926 and 1932 (Museum in the Streets gives the dates as 1929-1930, suggesting most of the work was done then).

The building is three stories tall on a granite foundation, with “rusticated brickwork” on the first level. (Wikipedia explains “rusticated” brick, masonry or stonework as having a rough outward surface that gives a textured appearance.)

The ground-floor front has three bays on its curve, each with an inset doorway with granite moldings around the doors. Brick plinths between bays support the two-story Tuscan columns above them; each bay has three tall windows on each floor.

The second and third floors are “separated by a wide, ornate stringcourse,” Mohney wrote. The stringcourse, a curved granite band, “is decorated with carved swags and an open book bearing the date 1926.”

Above the third floor another stone band has the words “CONY HIGH SCHOOL” in its three sections. A brick parapet with a clock with Roman numerals topped the front of the building.

Both sides were provided with a generous number of tall windows – fourteen to a side since a 1984 remodeling, Mohney wrote, almost twice as many originally. He described the fourth side of the building (the back) as having “two walls that meet at an obtuse angle” and variety in height and arrangement of doors and windows.

Inside, he wrote, the school was minimally decorated and had the wide staircases with landings that were typical of the period. The third-floor auditorium was the fanciest room, with a stage at one end and a balcony at the other and “Colonial Revival style details with classical moldings and pilasters.”

Wikipedia says the school was dedicated Dec. 12, 1930, although the top floor remained unfinished until 1932.

Again the number of students increased to exceed the capacity of the building, and an addition with more classrooms was built farther up the hill in 1963 or 1965 (sources differ). The addition and the enclosed, elevated walkway connecting it to the Flatiron were demolished, Wikipedia says in 2008.

A Cony graduate said she took most of her classes in the addition, but went to the old building for her typing class; she believes business and perhaps shop courses stayed in the Flatiron. The main difference she remembers is that Old Cony’s classrooms had high ceilings.

The present Cony High School at 60 Pierce Drive, next to the Capital Area Technical Center, opened in the fall of 2006, and Old Cony High School closed that year.

Wikipedia says the city used the Flatiron Building to store city property until 2013, when Housing Initiatives of New England leased it (for 49 years at a cost of $1 per year) and converted it to senior housing. The conversion maintained historic features, including stairs, corridors and most of the auditorium. New windows were designed to look like the old ones.

The Daniel Cony clock was preserved. It says on its face: “Presented by Hon. Daniel Cony. Time Is Fleeting.”

An article by reporter Keith Edwards in the July 19, 2015, Kennebec Journal describes the opening of the 48-apartment Cony Flatiron Senior Residence, with former Cony High School graduates among the first tenants.

Daniel Cony

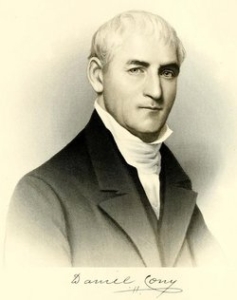

(Emily Schroeder, the archivist for the Kennebec Historical Society, wrote an article on Daniel Cony for the January-February 2020, issue of the Society’s newsletter, Kennebec Current. She was inspired by paintings of Cony and his wife on the wall of the society’s headquarters building. Much of the information on Daniel Cony is from her piece; other on-line sources and Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history have contributed.)

Daniel Cony (Aug. 3, 1752 – Jan. 21, 1842) was a Stoughton, Massachusetts, native who studied medicine in Marlboro, Massachusetts, under a doctor named Samuel Curtis. On Nov. 14, 1776, he married his preceptor’s niece, Susanna Curtis.

In April 1775, when the first battle of the American Revolution was fought, Cony was a doctor in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, about 70 miles west of Lexington and Concord. Soon after his marriage, he joined General Horatio Gates’ army at Saratoga, New York, and was there when British General John Burgoyne surrendered on Oct. 17, 1777.

Meanwhile, in 1777, his parents, Samuel and Rebecca (Guild) Cony, moved to Fort Western on the Kennebec River. Daniel and Susanna joined them in 1778, with their first daughter, Nancy Bass Cony, who died that fall at the age of 13 months. They subsequently had four more daughters, Susan Bowdoin, Sarah Lowell, Paulina Bass, and Abigail Guild Cony.

Daniel Cony was among the founders of the Unitarian church, in Augusta. He served Hallowell as town clerk and later a selectman; became a member of the legislature, first in Massachusetts and, after Maine became a separate state, in Maine; was a member of the state Executive Council, a Kennebec County judge and a delegate to the 1819 Maine constitutional convention.

Schroeder found that in the constitutional convention he argued for renaming Maine “Columbus,” in honor of the explorer. An opponent objected that Columbus never got far enough north to know there was such a place as Maine.

Despite – or perhaps because of – his own lack of formal schooling, Cony strongly supported education, including education for women. His creation of and support for Cony Female Academy are cited to explain why Augusta high schools have been named in his honor.

Additionally, he was representative to the Massachusetts legislature when it chartered Hallowell Academy in 1791 (Augusta was part of Hallowell then) and was on the academy’s first board of trustees. He helped found Bowdoin College in 1794 and, Schroeder wrote, was a Bowdoin “overseer” from 1794 to 1797. In 1820 Bowdoin gave him an honorary degree.

And the four Cony daughters:

— Susan (Dec. 29, 1781 – May 13, 1851) married Samuel Cony, her first cousin, on Nov. 24, 1803. Their son Samuel (1811-1870) was Governor of Maine from Jan. 6, 1864, to Jan. 2, 1867.

— Sarah (July 18, 1784 – Oct. 17, 1867) married Reuel Williams, member of another prominent Augusta family, in 1807. Their oldest child and only son, Joseph Hartwell Williams (1814-1896) was governor of Maine from Feb. 25, 1857 to Jan. 6, 1858, after Hannibal Hamlin resigned to return to the United States Senate.

— Paulina (Aug. 23, 1787 – Sept. 11, 1857) married Nathan Weston on June 4, 1809. He was one of the first Maine Supreme Court Justices (1820-1834) and second Chief Justice (1834-1841). Their grandson was United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller (see The Town Line, Dec. 10, 2020).

— Abigail (Jan. 17, 1791 – Nov. 29, 1875) married Rev. John Henniker Ingraham, from Portland, on Jan. 28, 1818, and died in Bangor.

Cony Female Academy

In 2002, the University of Maine provided a Women’s History Trail for Augusta that includes a history of Cony Female Academy, now available on line; and Henry Kingsbury summarized the academy’s history in his Kennebec County history.

Daniel Cony established the school to educate “orphans and other girls under the age of 16,” the University of Maine writer said. He speculated that Cony had in mind not only orphans, but also his own daughters, although by then all were adults and three were married.

Kingsbury wrote that Cony gave the 1815 building and its lot to a board of trustees, incorporated Feb. 18, 1818. The legislative act of incorporation referred to “the education of youth, and more especially females.”

Cony also provided Augusta Bank stock “and other gifts.” In 1826, the Maine legislature donated a half-tract of land, which the school sold for $6,000, and a Bostonian donated a $500 lot in Sidney. The school library had more than 1,200 volumes, given by Cony and others, making it one of the best in the area.

In addition to free education for orphans, the school admitted students who could afford to pay tuition, including boys. In 1825, tuition was $20 a year, with the trustees often contributing $10 a year for out-of-town students.

Besides the school building, the academy had a dormitory several blocks away where in the 1820s students boarded for $1.25 a week. Kingsbury wrote it was built in 1826 at the intersection of Willow and Myrtle streets, and was in 1892 Harvey Chisam’s home. The University of Maine writer located the dormitory at the intersection of Willow and Bangor streets, one block farther north.

By 1828, Kingsbury wrote, the academy’s property was valued at $9,795.

Hannah Aldrich, later Mrs. Pitt Dillingham, was the Academy’s first head, and continued her connection with the school into the 1840s. The Kennebec Historical Society has a picture of her when she was 92 years old.

After the school moved to the former Bethlehem Church in 1845, the original building became a house that “survived into the twentieth century” before being replaced by a filling station and later another building.

Kingsbury said the former Bethlehem Church was moved in 1880 to “its present [1892] location on the Fort Western lot at the foot of Cony Street.” The University of Maine writer said it was relocated down Cony Street to “a site near present-day [2002] City Center,” where it burned down in 1902.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous

Big Brothers Big Sisters of Mid-Maine has received a generous $30,000 Innovation Grant from United Way of Kennebec Valley (UWKV) to help launch a new program linking local law enforcement one-to-one with Augusta youth. The new program, called Bigs with Badges, is a collaborative partnership matching students from Sylvio J. Gilbert Elementary School (Littles) with Augusta Police Department law enforcement and first responders (Bigs), in long-term relationships that support local kids facing adversity.

Big Brothers Big Sisters of Mid-Maine has received a generous $30,000 Innovation Grant from United Way of Kennebec Valley (UWKV) to help launch a new program linking local law enforcement one-to-one with Augusta youth. The new program, called Bigs with Badges, is a collaborative partnership matching students from Sylvio J. Gilbert Elementary School (Littles) with Augusta Police Department law enforcement and first responders (Bigs), in long-term relationships that support local kids facing adversity.