Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Augusta families – Part 3

by Mary Grow

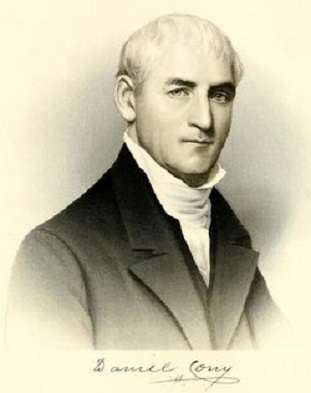

Daniel Cony

Daniel Cony (Aug. 3, 1752 – Jan. 21, 1842) has been mentioned in previous articles in this series in various contexts, including as the founder of Augusta’s Cony Female Academy and the man after whom Cony High School is named. He was profiled in the Sept. 2, 2021, issue of The Town Line.

Cony was born in Stoughton, Massachusetts, south of Boston, the third generation of a family that had lived there since his grandfather moved from Boston in 1728.

Kennebec Historical Society archivist Emily Schroeder called him “a Renaissance man” and “a man of many hats.” She, and most other historians, referred to him as a doctor; but, emphasizing his many roles, one source identified him as a jurist, and Charles Nash, in his chapter on Augusta in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, called him Judge Cony.

Cony learned medicine in Marlboro, Massachusetts, about 30 miles west of Boston, from a doctor named Samuel Curtis. By April 1775, when the first battle of the American Revolution was fought, one source said he was practicing medicine in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, farther west; James North, in his Augusta history, put him in Tewksbury, north of Boston.

By North’s account, Cony was “a lieutenant in a company of minute men.” Awakened at 2 a.m. by a messenger who shouted, “American blood has been spilled and the country must rally,” he joined his company at the pre-arranged meeting place, where they “paraded, received the blessing of the parish minister” and were on the way to Cambridge when the sun rose.

On Nov. 14, 1776, in Sharon, Massachusetts (abutting Stoughton), Cony married Susanna Curtis (May 4, 1752 – Oct. 25, 1833), daughter of Dr. Samuel Curtis’s brother, Rev. Phillip Curtis. Soon afterwards, he joined an infantry regiment sent to General Horatio Gates’ army at Saratoga, New York.

North told another dramatic story about Cony volunteering to lead a party across an area known to be under British guns. North wrote, “the young adjutant at the head of his men by his wary approach drew the enemy’s fire, felt the wind of their balls, then dashed forward with his command unharmed.”

Cony left the army after the war. His parents, Samuel and Rebecca (Guild) Cony, had moved to Fort Western on the Kennebec River in 1777. Daniel and Susanna joined them in 1778, with their first daughter, Nancy Bass Cony, who died that fall at the age of 13 months. They subsequently had four more daughters, Susan Bowdoin, Sarah Lowell, Paulina Bass, and Abigail Guild Cony.

North wrote that the family made their home on the east bank of the Kennebec. Their second house, built in the summer of 1785 and known in 1870 as the Toby House, was “just below the hospital” (the earliest iteration of Augusta’s insane asylum).

In 1797, North wrote, Colonel William Howard sold Cony a “beautiful spot on Cony street,” a bit farther north. Howard seldom sold land, but his estate had benefited from the new Kennebec bridge and Cony had been a bridge supporter, so Howard expressed his gratitude, North explained.

The first house Cony built on his new land burned in 1834, North said. Cony replaced it with a brick house where he lived the rest of his life.

Sources agree that Cony was successful as a doctor for many years. Augusta had few other doctors in the late 18th century; North mentioned Obadiah Williams, until he moved away, and one other.

In March 1789, North recorded (without explanation), Williams amputated a young man’s leg and “brought it…to Dr. Cony to dissect.”

Cony was a member of the Massachusetts Medical Society, North wrote, and “was on terms of intimacy and in correspondence with the leading medical men of Massachusetts.”

Schroeder wrote that in 1797 members of the Kennebec Medical Society elected him the organization’s first president.

Cony’s government service was varied. He was first elected Hallowell town clerk in 1785; North commented that after he took over, “the records began to assume a more regular form.” Schroeder wrote that he held the post until 1787.

Also in 1785, North wrote, a Hallowell town meeting chose Cony as delegate to a convention to be held in Falmouth in January 1786 to consider separating Maine from Massachusetts. At another meeting on Dec. 26, a five-man committee (including Ephraim Ballard) gave him instructions that North reprinted in full.

The instructions emphasized the committee’s desire to avoid conflict. Cony was to support separation only if “the people” were unanimously in favor and if it would not create discord or benefit one part of Maine over another. Any agreement must keep Maine in “the Federal Union,” and the committee members intended to continue to pay Maine’s share of the federal debt.

“Strengthened by the instructions,” North wrote, Cony went to Falmouth “and participated in the deliberations of the convention.”

This convention appointed a subcommittee that drew up a list of complaints about Massachusetts’ government, sent them to the towns whose delegates had attended and asked for representatives to another session in September 1786 to discuss separation. Hallowell voters again sent Cony.

At an April 1, 1786, town meeting, Cony was elected to his first term as representative to the Massachusetts General Court. In mid-April, North said, Cony wrote to the selectmen saying that he believed it was customary for legislators to reward their voters by standing a round at a local inn, to the tune of six or eight dollars; instead, he enclosed eight dollars, to be used for tax abatements for needy residents.

Schroeder wrote that Cony was also elected a Hallowell selectman in 1786; North did not name that year’s board.

The report of the September 1786 convention came to a Jan. 8, 1787, Hallowell town meeting. North recorded 35 voters favored “separation agreeably to the proceedings of the convention”; three disagreed. The majority then instructed Cony “to pursue such further measures as may be considered necessary to obtain a separation.”

Another statehood convention was called for September 1787, and Cony was again Hallowell’s delegate. By this time, North wrote, anti-statehood groups were organizing; the Massachusetts government was offering concessions, like establishing court sessions in Hallowell as well as Pownalborough (as mentioned in the article on James Howard two weeks ago); and interest in statehood waned briefly.

In 1788, North wrote, town meeting voters argued at length whether to send any delegate to the Massachusetts legislature. Eventually they voted to do so, 50 to 19, and re-elected Cony.

After the United States Constitution was adopted in 1787, on Dec. 18, 1788, Hallowell voters chose Cony as a presidential elector from the District of Maine. He also received votes for representative to Congress, but was out-polled by George Thatcher, a “distinguished lawyer” from Biddeford.

In 1789, Schroeder and North agreed, town meeting voters elected Cony one of Hallowell’s three selectmen.

By Hallowell’s May 2, 1791, town meeting, separation from Massachusetts was again being considered. As North told the story, the north-south division that would lead to the separation of Hallowell and Augusta in February 1797 was also in play.

The meeting began with a vote on sending a representative to the Massachusetts General Court, approved 41 to 38. A motion to reconsider was then approved, and this time representation was rejected, 20 in favor and 40 against.

After the election, North wrote, a separate meeting “for the transaction of town business” appointed Cony and four others a committee to consider separation from Massachusetts.

Enough voters, mostly from the area that would remain Hallowell, objected to the first action on May 2 to get another meeting called May 13. This time the vote to continue to be represented in Massachusetts was 52 to 46; Cony was elected over William Howard, on a 61-46 vote.

The May 2 committee then reported, favoring separation and urging a Lincoln County convention authorized to draft a state constitution. Voters approved 50 to 20.

The Massachusetts General Court did not approve, and instead in March 1792 called for special town meetings. Hallowell’s, held May 7, approved separation by a 56 to 52 vote; other towns voted the other way and separation was defeated.

Proponents brought the question to a November 1793 Hallowell meeting and asked for a delegate to a convention in Portland. Cony was chosen, “by 36 votes”; North blamed the low number on bad weather.

Meanwhile, in May 1792 Cony had been re-elected representative to the General Court; but he was also elected a senator, so in September a new representative was elected. North wrote that the same thing happened in 1795.

In the fall of 1792 several sources said Cony was a Massachusetts member of the electoral college that elected President George Washington to a second term. In 1794, he was again in the Massachusetts legislature.

Cony moderated a 1794 meeting that divided Hallowell into three parishes, a movement toward the division into two towns. North said after the “lengthy and warm discussion,” voters formally thanked Cony for “his impartial services as moderator.”

In May 1796, voters in future Augusta petitioned the General Court to divide Hallowell and appointed Cony to present the petition. It was approved Feb. 27, 1797; the new town named Harrington was officially renamed Augusta on June 8.

Cony moderated Harrington’s first town meeting, held April 3, 1797. He was Augusta’s delegate to an Oct. 23, 1798, convention that petitioned for the separation of Kennebec County from Lincoln County, a request granted Feb. 20, 1799.

Cony served on Kennebec County’s Court of Common Pleas. He was a judge of probate before and after Maine statehood; he retired in 1823.

In 1819, Schroeder wrote, Cony was chairman of the Portland meeting where delegates discussed a constitution for the about-to-be-created State of Maine. She called his suggestion that the new state be named Columbus (after Christopher Columbus) “unfortunate.”

North recorded that, like Ephraim Ballard, Cony served on local committees charged with finding a minister, beginning in 1786, when the choice of Rev. Isaac Foster generated years of controversy, in which Ballard and Henry Sewall were involved. Cony served on similar committees in 1792, 1794 and 1809.

That Cony was an active church-goer is attested by references to him as Deacon Cony. North recorded occasions on which he filled in as a preacher.

In 1806, he was one of a committee tasked with choosing a site and building a new meeting house for the “first Congregational society in the South parish.”

All his life, Cony was a promoter of education. North wrote that in the Massachusetts legislature, Cony actively supported a petition for “the incorporation and endowment” of Hallowell Academy, approved March 5, 1791. A new building was built to house the school, and it opened May 5, 1795, North wrote. In 1821 Cony was president of the Academy’s board of trustees.

In 1793 Cony was one of five men appointed a committee to oversee local schools.

Requests for a college in Maine began coming to the General Court in 1788, with proposed locations in Portland, Gorham and Freeport. In 1794, a three-man committee directed Cony, as a Massachusetts legislator, to do his best to get a Maine college established and funded.

The result, North wrote, was Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, chartered June 24, 1794, and given “five townships of land” from which to generate income. Cony was a member of the board of overseers from 1794 to 1797.

(North and Cony would have agreed on this topic, judging by North’s rhapsodic comments on a 1789 Massachusetts law regarding public schools. “This early provision by the parent commonwealth for the education of the people is one of those luminous pages in her history which shed their light upon every step she has taken in the pathway of her greatness,” he wrote.

The law “commanding” that everyone be educated, he continued, was to ensure “that a broad and sure foundation for republican government might be laid in the intelligence and virtue of the people.”)

In his spare time, Cony became a corporator of the Lincoln and Kennebec Bank and of the Augusta and Hallowell Bank, both in 1804, and a director of the Augusta bank in 1814. In April 1807 he became treasurer of the Kennebec Agricultural Society.

In 1808 he was one of a number of men who organized themselves into patrols to keep watch at night during the uprising of settlers defending their right to the lots they lived on (mentioned in earlier stories in this series in the July 2, 2020, and Oct. 27, 2022, issues of The Town Line).

In 1826, North wrote, Augusta celebrated Independence Day “with great festivity” appropriate for a 50th anniversary. “Hon. Daniel Cony, aged and venerable,” (he would have been about to celebrate his 74th birthday) presided at a dinner and made a speech, though he did not stay for the fireworks.

The next year, Cony was on a committee preparing for the establishment of the state capital at Augusta.

Cony, in his old age, and historian North, in his youth, attended the South Parish meeting house. North described Cony, erect and dignified, dressed in a “tartan plaid coat,” with a red worsted cap over his “locks frosted to a snowy whiteness by age” and carrying a cane “by its center so that its large ivory head appeared above his shoulder.

Daniel and Susanna Cony, his parents and other family members are buried in the Cony cemetery, also called the Knight cemetery, on Hospital Street, in Augusta, just south of the Piggery Road intersection.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.