Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Social clubs in Kennebec Valley

by Mary Grow

Last week’s article talked mostly about ways early settlers interacted socially as individuals and families. This week’s piece will describe some of the 19th-century organizations that united residents and kept them busy, and related topics.

Kennebec Valley towns had a variety of organizations, some branches of national groups and others home-grown. Some built headquarters buildings; other groups met wherever they could, in public spaces or private homes.

In her chapter on social life in Edwin Carey Whittemore’s centennial history, Martha Dunn described some of Waterville’s 19th-century organizations. Separate chapters listed others.

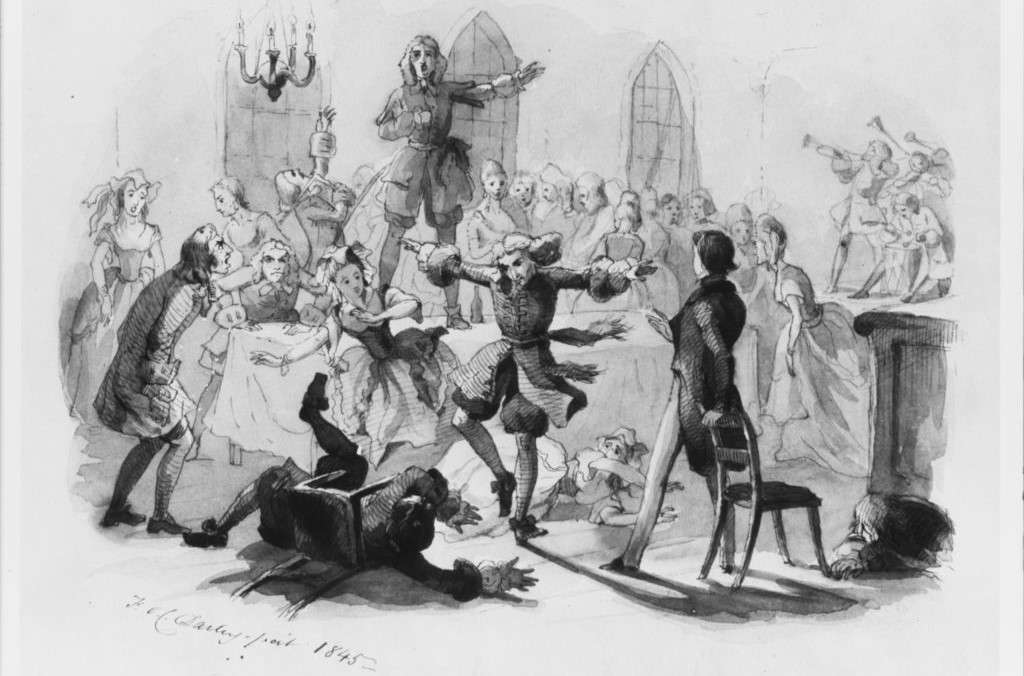

The first Waterville literary organization for which Dunn found records was the Shakespearean Club, whose members presented Shakespeare’s plays. Started about 1852, it included men and women. Meetings were held weekly “during the winter season” at members’ houses.

Dunn named two members: Baptist church pastor Rev. N[athaniel] Milton Wood, “a man of strict tenets and naturally lugubrious cast of countenance,” who reportedly “not only excelled but delighted in the representation of comic parts”; and Mrs. Ephraim Maxham (the former Eliza Anna Naylor, according to on-line sources), wife of the Waterville Mail owner-editor, who “was especially skilled in the rendering of tragedy.”

The club disbanded during the Civil War and after the war reformed as the Roundabout and continued another half-dozen years, becoming, Dunn wrote, less intellectual and “more given to feasting and social enjoyments.”

Mrs. James H. Hanson (the former Mary E. Field, of Sidney) wrote a chapter in Whittemore’s history on the Waterville Women’s Association, an organization praised by Dunn and in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history. Dunn called it the place “where women may work – and enjoy – together, independent of society distinctions or church affiliations.”

A wealthy widow named Sarah Scott Ware (Mrs. John Ware, Sr.) founded the Association in 1897, with working women and girls foremost in her mind. She wanted to provide a “homelike” place for them, with “facilities for literary and womanly culture and usefulness,” beginning with a lending library.

By 1902 the club had well over 100 members. Its rooms provided books, magazines and newspapers; games; and a sewing machine. Women and girls attended late-afternoon programs and evening classes (Kingsbury listed instruction in “needlework, penmanship, music and a variety of useful arts”). The group ran a lunchroom, an employment bureau and a second-hand clothing distribution center.

Funding came from donations and, Hanson wrote, “the successful doll sales and May-basket sales.” For those she credited the enthusiasm and skill of the young members; they “were also indispensable in the work of the schools,” she wrote.

The Women’s Association spun off the Women’s Literary Club in the winter of 1891-1892. Dunn wrote the members met “fortnightly during the winter season” for literary and musical programs, gathering in church vestries, at Waterville Classical Institute (so named in 1865; after 1883, Coburn Classical Institute) or in members’ houses.

A separate club called the Literature Class, with a dozen members, met weekly “during the winter months.”

Augusta, according to Kingsbury, had a Benevolent Society, started about 1842 “by Miss Jane Howard, a maiden lady whose name is still fragrant in this community, by reason of her many deeds of benevolence and charity.” Later renamed the Howard Benevolent Society and in 1883 The Howard Benevolent Union, Kingsbury said its work was primarily “clothing the poor.”

The Fairfield bicentennial history records a Ladies Book Club, started in 1895. As described in the Nov. 11, 2021, The Town Line, one founding member was Addie Lawrence, whose father a few years later donated money to build Fairfield’s Lawrence Library.

Vassalboro historian Alma Pierce Robbins listed – without dates – four clubs, at least three identified as women’s clubs, and said two of them “met at members’ homes year ’round.”

In Palermo, historian Milton Dowe wrote, the Branch Mills Ladies Sewing Circle first met on March 10, 1853, hosted by Mrs. B. Harrington (almost certainly the wife of Barzillai Harrington; he was recognized in the Sept. 23, 2021, issue of The Town Line for starting a high school in China’s side of Branch Mills Village about 1851).

The sewing circle remained active for years; its members were responsible for construction of the Branch Mills Community House in 1922.

Among national/international organizations with local affiliates, the Masons, mostly the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (A. F. & A. M.), had branches in many Maine towns.

Windsor had Malta Lodge for about five years in the 1880s, according to Leonard Lowden’s town history. Members customarily met “weekly on Saturday nights.” After the lodge shut down, on “Saturday evening, December 12, 1885,” the few Windsor men still interested joined the lodge in Weeks Mills, “on Saturday night, May 29, 1886.”

Kingsbury wrote that Benton’s Lodge was organized Nov. 21, 1891, and as he finished his county history in 1892 was “in a flourishing condition.” Members met every Thursday evening in one of Benton’s schoolhouses.

Masonic lodges were also noted in histories of Augusta (four lodges, the earliest founded in 1821); China (four lodges, the first dating from 1824); Clinton (Sebasticook Lodge, chartered in May 1868); and Fairfield (Siloam Lodge, chartered March 8, 1858, with 13 members).

Sidney’s branch of the A. F. & A. M. was Rural Lodge No. 53, according to Alice Hammond’s town history. A dozen men, some members of a lodge in Waterville, started it on April 25, 1827.

The lodge disbanded in 1836, she wrote, “because of the violent anti-masonic feeling which prevailed at that time.” The China bicentennial history expanded on that theme, quoting from Thomas Burrill’s history of Central Lodge.

Burrill said “Antimasonry” started about 1829 and soon “assumed a most formidable type of persecution, both against Masons and Masonry.” Central Lodge members got rid of their paraphernalia, sending “their beautiful painted flooring” to a Lodge in St. Croix and abandoning their hall. The Lodge reassembled in 1849.

Sidney’s Rural Lodge was revived in 1863, Hammond said. A Masonic Hall was built in 1887 and dedicated Jan. 3, 1888. After the dedication and installation of officers, members went to Sidney Town Hall “where a bountiful repast was served and a social time enjoyed.”

Rural Lodge No. 53 is still active, listed on a Maine Masons website, with a photo of the white wooden lodge hall at 3000 Middle Road. The website also lists Lodges in Augusta, China (China Village), Clinton, Fairfield, Waterville and Weeks Mills (China).

The Order of the Eastern Star, related to the Masons and open to women and men, had branches in China, Fairfield and Waterville, among other towns.

Another widely represented organization was the Independent Order of Good Templars (I. O. G. T.). Founded in New York State in 1852, it soon became an international temperance organization open to men and women. Maine’s Grand Lodge of the I. O. G. T. was created in the summer of 1860.

The Sons of Temperance, founded in 1842, also organized in the area, including, Kingsbury wrote, three local branches in China.

In Vassalboro, historian Robbins saw temperance as an issue from the 1820s. In 1821, eight “innkeepers” got liquor licenses, she wrote; by 1829 Congregational pastor Rev. Thomas Adams was preaching temperance.

In 1834, Robbins wrote, Vassalboro’s Juvenile Temperance Society was organized. The president was Abiel John Getchel; an on-line search found a Vassalboro resident of that name (spelled Getchell) born in Vassalboro in 1815, so 19 years old in 1834. One of three executive committee members was Greenlief Low, born in 1817.

Vassalboro had three I. O. G. T. Lodges, Robbins wrote. Each had its own meeting hall: “a nice little hall” at Riverside (demolished in the 1930s): “Golden Cross Hall” in North Vassalboro; and Maccabees Hall “in Center Vassalboro or Cross Hill.”

The buildings were supposed to be only for the organizations’ events, Robbins wrote, but later she said Maccabees Hall was the scene of “many meetings.” The Riverside hall hosted dances, “Christian Endeavor plays” and “demonstrations of ‘fireless cookers'” by the University of Maine Extension Service.

(Wikipedia says The Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavour was founded in 1881 in Portland by Rev. Francis Edward Clark, with the goal of bringing young people to interdenominational Christian belief and work. By 1906 there were more than four million members around the world in “67,000 youth-led…societies.” Causes members supported included temperance.)

Dowe wrote the Good Templars and Christian Endeavor were active in 19th-century Palermo. The East Palermo schoolhouse, he wrote, served as a community center and “church for prayer meetings and the Young People’s Christian Endeavor.”

The schoolhouse also hosted singing, spelling and writing schools, Dowe said. When phonographs first came to Palermo, an unspecified group or person would charge admission to listen to one in the schoolhouse.

In her history of Sidney, Alice Hammond found another reference to phonograph shows: she reproduced a poster advertising PHONOGRAPH!, an exhibition starting at 7:30 p.m., Friday, Feb. 5, 1892, at the Grange Hall, in Centre Sidney.

“There will be an exhibition of the marvels of the modern phonograph,” the poster promised. “It Will Talk, Laugh, Sing, Whistle, Play on all sorts Instruments including Full Brass Band.”

Professor R. B. Capen, of Augusta, would explain the device. Admission was 20 cents, half price for children under 12.

The exhibition would be followed by a supper “Furnished at the Hall” and a Grand Ball, with music by Dennis’ Orchestra of Augusta, dance tickets sold at 50 cents for each couple and dancing until 2 a.m.

Another organization Lowden noted was the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), the Civil War veterans’ organization founded in 1866 in Illinois and dissolved in 1956 after its last member died. The Windsor post was organized June 2, 1884, and met in its hall on the second floor of the town house “on each Saturday night” (with at least one Wednesday evening gathering – see the paragraphs on Civil War soldier Marcellus Vining in the March 31, 2022, issue of The Town Line).

Augusta had Masons and Odd Fellows; a lodge of the Knights of Honor (its chief officer’s title was dictator, according to Kingsbury); Dirigo Council No. 790 of the Royal Arcanum (1883); and Tribe No. 12 of the Independent Order of Red Men (1888).

Late 19th-century organizations in Fairfield included local Masons and Odd Fellows; an Eastern Star chapter; and the Past and Present Club, organized by 15 women in 1892 and accepted into the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1899.

Waterville had Masons, Odd Fellows, Good Templars, a Tribe of Red Men and numerous other groups. Whittemore listed Hall’s Military Band, the late-19th-century successor to local brass bands first organized in 1822; a choral group named the Cecilia Club, organized in 1896; and since 1892 the Waterville Bicycle Club and the Waterville Gun Club.

The Bicycle Club, Whittemore wrote, rented an entire floor of the Boutelle Block at Main and Temple streets. The premises hosted meetings and social events; gambling and liquor were banned.

The Gun Club’s five-man team won state championships in 1897, 1898 and 1901. The club produced two individual state champions, Walter E. Reid once and Samuel L. Preble twice (no years given).

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 (1954).

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.