The Civil War left China, like Albion and other towns, deeply in debt, paying to outfit the soldiers and compensate their families.

Civil War

The United States Civil War, which began when the Confederates shelled Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, and ended with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, had the most impact on Maine, including the central Kennebec Valley, of any 17th or 18th century war.

Nonetheless, your writer’s original plan was to write only a single article about the Civil War. As usual, she found an oversupply of material that she hopes will interest readers as it interested her; but she still limits coverage to two articles, for three reasons.

The first and most important reason to downplay Civil War history is that unlike, say, the War of 1812, the Civil War is already familiar. Citizens who know nothing about the Sept. 13, 1814, bombardment of Fort McHenry (which inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem that became the national anthem) recognize at least the names of battles like Bull Run and Gettysburg. Many people can name at least one Civil War general; few can name one from the War of 1812.

A second point is that numerous excellent histories of the Civil War are readily available, including books specifically about Maine’s role.

And the third reason is that this war is recent enough that some readers undoubtedly have memories of their grandparents telling stories of the generation before them who fought in the Civil War.

Any reader who would like to share a family Civil War story is invited to write it, attach photographs if available and email to townline@townline.org., Att. Roland Hallee. Maximum length is 1,000 words. Submissions will be printed as space permits; the editor reserves the right to reject any article and/or photograph.

* * * * * *

Maine historians agree that the majority of state residents supported President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to fight to preserve the Union. Those who initially disagreed, James W. North wrote in his history of Augusta, found themselves a small enough minority so they either changed their views or moderated their expression.

By 1860, the telegraph was widely used. News of Fort Sumter reached Augusta the same day, followed two days later by Lincoln’s call for 75,000 three-months volunteers, including one regiment from Maine.

On April 22, North wrote, the Maine legislature, in a hastily-called special session, approved enrolling 10,000 soldiers in ten regiments for three years, plus “a State loan of one million dollars.”

Augusta had filled two companies by the end of April. Other Kennebec Valley companies joined them; they camped and drilled on the State House lawn. The Third Regiment started south June 5, 1861; those soldiers were promptly replaced by others from other parts of Maine, volunteers succeeded by men paid bounties and in 1863 by draftees.

North wrote that the first draft in Augusta was held July 14 through 21, 1863, starting two days after the New York City draft riots began, with news arriving hourly. In Augusta’s Meonian Hall, eligible men’s names were drawn from a wheel by a blindfolded man named James M. Meserve, “a democrat of known integrity and fairness, who possessed the general confidence.”

The process began with selection of 40 men from Albion. Augusta followed, and, North wrote, the initial nervousness gave way to “a general feeling of merriment,” with draftees being applauded and congratulated.

Being drafted did not mean serving, North pointed out. Physical standards were strict; out of 3,540 draftees, 1,050 were “rejected by surgeon for physical disability or defects.” It was also legal to pay a substitute or to pay the government to be let off.

Augusta remained a military hub and a supply depot through the war, centered around the State House and Camp Keyes, on Winthrop Hill, at the top of Winthrop Street. There were large hospital buildings on Western Avenue, North wrote, which were so crowded by 1863 that the Camp Keyes barracks were also fitted up as hospital wards. The trotting park between the State House and the river was named Camp Coburn and hosted infantry and cavalry barracks and enlarged stables.

North described the celebratory homecomings for soldiers returning to Augusta when their enlistments were up, like the one in August 1863 for the 24th Regiment. The “bronzed and war-worn” men had come from Port Hudson, Louisiana, up the Mississippi to Cairo and by train to Augusta, a two-week trip. Greeted by cannon-fire, bells, torch-carrying fire companies, a band, state and city officials and “a multitude” of cheering citizens, they marched straight to the State House, enjoyed a meal in the rotunda and “dropped to sleep on the floor around the tables, being too weary to proceed to Camp Keyes.”

Historians describing the effects of the Civil War on smaller Kennebec Valley towns tend to emphasize two points: the human cost and the financial cost.

Ruby Crosby Wiggin found as she researched the history of Albion a record saying that “out of 100 men who went to war from the town of Albion, 45 didn’t come back.” She listed the names of more than 150 Albion soldiers, six identified as lieutenants.

By 1862, Wiggin wrote, the state and many towns offered enlistment bonuses. In addition, towns paid to equip each soldier. Total Albion expenditures, she wrote, were $21,265; the state reimbursed the town $8,033.33.

Wiggin concluded, “No wonder the town was heavily in debt at the close of the Civil War.”

The China bicentennial history says almost 300 men from that town served in Civil War units. The author quoted from the 1863 school report that said attendance in one district school was unusually low, “the large boys having gone to the war.”

The Civil War left China, like Albion and other towns, deeply in debt. The China history says when the State of Maine began tallying municipal costs and offering compensation in 1868, China had paid $47,735.34 to provide soldiers. The state repayment was $12,708.33, and town meetings were still dealing with interest payments and debt repayments into the latter half of the 1870s.

China town meetings during the war were mostly about meeting enlistment quotas, and, the history writer implied, by 1864 voters were tired of the topic. In July and again in December 1864, they delegated filling the quota to their select board.

When the late-1864 quota had not been filled by February 1865, voters were explicit; the history writer said they agreed to “sustain the Selectmen in any measures they may take in filling the quota of this town.”

The Fairfield historians who wrote the town’s 1988 bicentennial history found the list of Civil War soldiers too long to include in their book and noted that the names are on the monument in the Veterans Memorial Park and in the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) record books in the public library across Lawrence Avenue from the park.

Of Larone, the northernmost and likely the smallest of the seven villages that made up the Town of Fairfield for part of the 19th century, the history says, “Larone furnished her full quota of ‘boys in blue’. These averaged one for every family, three-fifths were destined never to see their homes again.”

Millard Howard, in his Palermo history, wrote that “The Civil War was by far the most traumatic experience this town ever experienced.” Of an 1860 population of 1,372, 46 men, “or one out of every 30 inhabitants,” died between 1861 and 1865.

Looking back from the year 2015, Howard wrote somberly, “No other war can remotely compare with it.”

He listed the names of the dead, with ages and causes of death where known. The youngest were 18, the oldest 44. More than half, 26, died of disease rather than wounds; Augustus Worthing, age 31, starved to death in Salisbury prison, in North Carolina.

Sidney voters spent a lot of town meetings in the 1860s talking about the war, according to Alice Hammond’s town history. As early as 1861, they approved abating taxes for volunteers.

As the war went on, voters authorized aid for volunteers’ families and monetary inducements to enlist for residents and non-residents, with preference given to residents. At an 1863 special meeting, they authorized selectmen to borrow money as needed “to aid families of volunteers.”

Hammond noted that Sidney was debt-free before the war, “but in 1865 it issued bonds for $24,000, a debt from which it recovered very slowly.”

Alma Pierce Robbins found from military records that 410 men from Vassalboro enlisted for Civil War service. From census records, she listed the 1860 population as 3,181.

As in other municipalities, voters approved wartime expenses. Robbins wrote that $7,900 was appropriated for bounties and aid to soldiers’ families in 1861. The comparable 1863 figure was $16,900. Perhaps for contrast, she added the 1864 cost of the new bridge at North Vassalboro (presumably over Outlet Stream): $1,057.82 (plus an 1867 appropriation of $418.62).

In Waterville, General Isaac Sparrow Bangs wrote in his chapter on military history in Reverend Edwin Carey Whittemore’s 1902 centennial history, recruiting offices opened soon after the news of Fort Sumter. A Waterville College student named Charles A. Henrickson was the first to enroll, and, Bangs wrote, his example “proved so irresistibly contagious at the college that the classes and recitations were broken up” and the college temporarily closed.

Henrickson was captured at the Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861. He survived the war; later in the Waterville history, Chas. A. Henrickson is listed among charter members of the Waterville Savings Bank, organized in 1869.

These Waterville soldiers became companies G and H in the 3rd Maine Infantry, Bangs wrote. After drilling in Waterville, they went to Augusta and were put under the command of regimental Colonel Oliver O. Howard. On June 5, Howard was ordered to Washington, “carrying with him, as Waterville’s first contingent, seventy-four of her boys into the maelstrom of war.”

Bangs spent years verifying the names of 421 men who either enlisted from Waterville or were Waterville natives who enlisted elsewhere. The names are included in Whittemore’s history.

Bangs added that the Maine Adjutant-General’s report says Waterville provided 525 soldiers. He offered several explanations for the discrepancy, pointing out the difficulties of accurate record-keeping.

Waterville paid $67,715 in enlistment bounties, Bangs wrote. Henry Kingsbury, in his history of Kennebec County, put the figure at $68,016 and said the state reimbursement was $19,888.33.

Linwood Lowden wrote in the history of Windsor that more than one-third of Windsor men aged 17 to 50 fought in the Civil War, most of them in the19th and 21st Maine infantry regiments.

Like other towns, Windsor paid bonuses to enlistees and, Lowden wrote, $2,663.87 “in aid to soldiers’ families…from 1862 through 1866.” He added that Windsor first went into debt during these years.

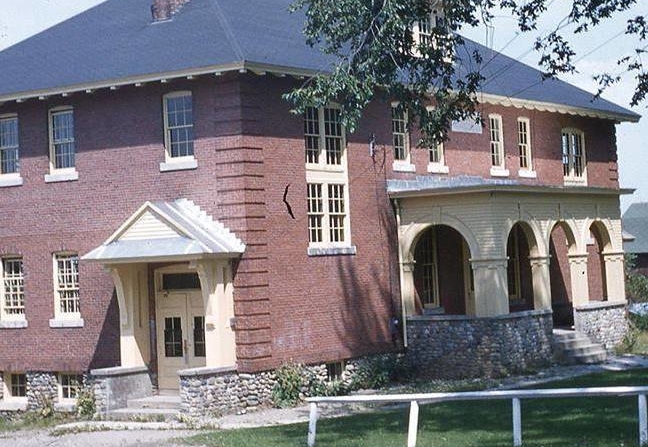

Camp Keyes, Augusta

A history of Camp Keyes found on-line says that the 70-acre site on top of Winthrop Hill, on the west side of Augusta, had been used as, and called, “the muster field” since before Maine became a state in 1820. It was still available, although the militia had become less significant, when the Civil War broke out.

On Aug. 20, 1862, Maine Adjutant General John L. Hodsdon designated the field one of Maine’s three official “rendezvous areas” for militia and volunteers and named it Camp E. D. Keyes, in honor of Major-General Erasmus D. Keyes, a Massachusetts native who moved to Kennebec County (town unspecified on line) as a young man. He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1832 and fought in the Civil War until 1863, when a superior removed him from command, claiming he lacked aggressiveness.

(The other two Maine rendezvous areas were Camp Abraham Lincoln, in Portland, and Camp John Pope [honoring General John Pope from Kentucky], in Bangor.)

Thousands of Civil War soldiers from Maine passed through Camp Keyes. It also housed Maine’s only federal military hospital, named Cony Hospital in honor of Governor Samuel Cony.

After the war, the site remained a militia training ground. The State of Maine bought it in 1888. In 1893 the militia became the National Guard and continued to use the training ground, with Guard headquarters in the Capitol building until 1938.

The on-line site gives an undated description: “Small buildings were constructed of plywood for mess halls, kitchens, latrines, store houses, and lodging for senior military officers. Companies pitched their tents on pads that had been built.”

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

The following students have been named to the dean’s list for the 2021 fall semester at the University of New England, in Biddeford. Dean’s list students have attained a grade point average of 3.3 or better out of a possible 4.0 at the end of the semester.

The following students have been named to the dean’s list for the 2021 fall semester at the University of New England, in Biddeford. Dean’s list students have attained a grade point average of 3.3 or better out of a possible 4.0 at the end of the semester.