Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Clinton

by Mary Grow

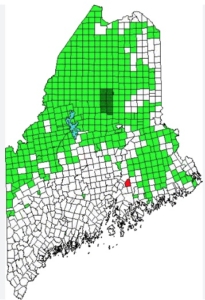

The town of Clinton, Benton’s ancestor and northern neighbor, is the northernmost Kennebec County town on the east bank of the Kennebec River. Historian Carleton Edward Fisher wrote that Clinton’s first white settler was probably Ezekiel Chase, Jr., who might have arrived by 1761, before the Kennebec Proprietors claimed the area.

Fisher called the first settlers “poor but industrious and daring.” They were homesteading in a wilderness “beyond the protection of Fort Halifax”; he said they did not feel totally “safe from Indian threats” until after the War of 1812.

Fisher wrote that by the end of 1781, 25 families plus about a dozen single men had lived in the area long enough to leave a record. Areas where they homesteaded extended up the Kennebec River to the town’s western boundary, up the Sebasticook River only to Benton Falls.

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, dated the first settlers at around 1775, after the area became part of the Plymouth Patent. By the time it (including both Benton and Clinton) was incorporated as Hancock Plantation “in or before 1790,” the population was 278, he said.

Fisher wrote that Hancock Plantation was never officially incorporated – at least, he could find no Massachusetts legislative record of the action. Nor could he find any plantation records.

No one your writer found explained the choice of the name “Hancock.” The present town of Hancock, Maine, in Hancock County, was reportedly named after John Hancock, a signer of the Declaration of Independence – as was Hancock County.

On Feb. 27, 1795, the Massachusetts legislature incorporated Hancock Plantation as the Town of Clinton. Fisher wrote that “a highly respected citizen,” Captain Samuel Grant, chose the name to honor Revolutionary War General Clinton, under whom he had served and “whom he deeply admired.”

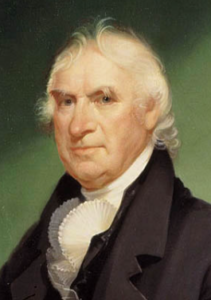

Wikipedia identifies this general as George Clinton (July 26, 1739 – April 20, 1812), governor of New York from 1777 to 1795 and (partly at the same time) a brigadier general, first in the state militia and later in the Continental Army.

Clinton’s military service started in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Wikipedia says. He served on a privateer operating in the Caribbean before joining the New York militia, where his father was a colonel and he became a lieutenant.

Elected to the provincial assembly in 1768, Clinton opposed British taxation publicly enough to be chosen a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, serving from mid-May 1775 to July 8, 1776.

On Dec. 19, 1775, New York’s Provincial Congress (the interim government that convened May 22, 1775) made Clinton a brigadier general in the state militia. The Wikipedia writer says he was by then strongly pro-independence, “even suggesting in one speech to Congress that a reward should be offered for the assassination of King George III.”

On March 25, 1777, Clinton became a brigadier general in the Continental Army, where he served until Nov. 3, 1783. In June 1777 he was elected both governor and lieutenant governor of New York; he accepted the governorship and served from July 30, 1777, to June 1795.

Clinton remained active in politics into the next century. He served as vice-president in Thomas Jefferson’s second term (1805-1809) and in James Madison’s first (1809 – 1813), during which he died of a heart attack on April 20, 1812.

* * * * * *

Kingsbury’s early history of the Town of Clinton references the part that became Benton frequently, and Fisher wrote that the southern part of town played a “dominant role” in early days. The majority of the population lived there in 1795, and the first town meeting was held there, at Captain Jonathan Philbrook’s house on April 20, 1795.

At a March 1797 meeting, Kingsbury wrote, voters appropriated $300 for eight school districts (with 166 students), “nearly all of which lay in what is now Benton.”

Fisher provided clarification about the Flagg family, mentioned last week. According to his history, the Gershom Flagg who came to Clinton was Gershom Flagg, Jr., son of the early Augusta settler.

The younger Gershom Flagg was born Sept. 1, 1743, Fisher said. He married twice, on Feb. 10, 1773, to Sally Pond, of Dedham, Massachusetts, and after her death, to Abigail Bigelow of Waltham, Massachusetts (no date given). His two wives gave birth to four daughters and four sons between 1773 and July 1800; Sally’s first son was the third Gershom in the family.

In September 1798, Fisher wrote, Gershom Flagg, Jr., and Joseph North, from Augusta, signed an agreement under which they built a double sawmill (presumably on the Sebasticook). Here Flagg was killed “by logs rolling on him” on May 6, 1802.

Fisher wrote that Flagg held “a number of town offices, including town clerk from 1796 to his death.” His son, the third Gershom, succeeded him as town clerk from 1802 through 1806.

Town meetings were held in school houses until the spring of 1833, Fisher wrote. By around 1815, settlers on the Kennebec and those on the Sebasticook were disagreeing about which community should host each meeting. The first discussion of building a town hall was in 1816.

In November 1831, Fisher said, voters approved building their town hall on Town House Hill, on what he said was then the Morrison Corner Road, “near Abiathar Woodsum’s store.” The location in southern Clinton, west of Clinton Village, was close to population concentrations at Morrison’s and Decker’s corners but still a distance from Pishon’s Ferry on the Kennebec.

The building was used until 1898, Fisher said, “when the present [1970] town hall was built.” In 1905, he found, the old town house was moved to an adjacent farm and made a barn, which was torn down in the spring of 1968.

As described in last week’s article, on March 16, 1842, the Maine legislature made the southern part of Clinton, almost half its about 75 square miles, a separate town that was first Sebasticook and soon afterwards Benton.

Present-day Clinton is bounded on the west by the Kennebec River. The Sebasticook River loops north, south, east and north again in its southeastern corner.

Kingsbury, writing in 1892, identified six population centers: Clinton Village, in the southeastern part of town on the northern curve of the Sebasticook; two villages near ferries on the Kennebec, Noble’s Ferry and about two miles farther up river Pishon’s Ferry; and three corners, Morrison’s, Decker’s, and Woodsum’s.

Clinton Village on the Sebasticook, is now downtown Clinton. Kingsbury counted its first settlers as Jonathan Brown, Asa Brown and “a Mr. Grant.” The last two began farming on the Sebasticook within a mile of the village before 1798, he said. An on-line genealogy adds Jesse Baker and “Mr. Michels” before 1800, and James and Charles Brown by 1812.

Kingsbury dated the first mills in the village, on a dam, to the mid-1830s. They were built by members of the Brown and Hunter families. Kingsbury and an on-line source disagree on some of the Hunters’ first names, but agree that one was named David and was known locally as “King David,” the on-line site says “because of his masterful ways.”

The downriver Kennebec ferry, Fisher wrote, was started by Benjamin Noble, who lived on the west (Fairfield) side of the Kennebec in 1770, in Clinton in 1787 and in Fairfield in 1790. Dean Wyman probably took over the service in 1791; Fisher found a 1797 reference to Wyman’s Ferry. Kingsbury, writing in 1892, said the ferry was “abandoned about twenty years ago.”

Pishon’s Ferry was started by Charles Pishon (originally Pichon, a family who settled in Dresden, Maine), probably around 1790 when he moved to Clinton. Pishon died around 1830 (Fisher) or 1840 (Kingsbury), but the ferry continued until the river was bridged there in 1910.

The 1856 and 1879 Kennebec County atlases show a significant settlement – 10 or so houses in 1856, half again as many in 1879 – at the Clinton end of Pishon’s Ferry, but no such concentration at the Noble’s Ferry landing.

At Pishon’s Ferry, Kingsbury listed farmers; the first tavernkeeper, before 1815; a doctor who set up his practice about 1815; several men who established mills on Carrabassett Stream, which flows into the Kennebec there, from 1815; and storekeepers from 1832.

Morrison’s Corner, where Hinckley Road is intersected by Peavey and Battle Ridge roads, appears on many maps. Kingsbury wrote that the first settler there was Mordecai Moers, who reportedly lived to be 105. The first Morrison, James, came about 1820; the 1856 map shows a J. Morrison on the northwest side of the intersection.

Decker or Decker’s Corner is shown on the 1879 map northeast of Morrison’s Corner; a J. Decker lived there. Kingsbury wrote that Joshua Decker and family settled near the corner about 1797; Joshua’s son Stephen (1780-1873) ran a store in the 1820s; and in 1892 at least two Decker families lived near the corner.

Woodsum’s Corner Fisher identified with Town House Hill. Kingsbury said Abiather (Kingsbury’s minority spelling; other sources say Abiathar) Woodsum (1786-1847) came there before 1820; Daniel Holt and Grandnief Goodwin had stores nearby.

Here, Fisher wrote, was one of Clinton’s six post offices, the North Clinton one. It opened June 10, 1825, in Woodsum’s store, and Woodsum was postmaster until Oct. 13, 1842.

The other five post offices Fisher listed as:

— Clinton, opened July 29, 1811, on the west side of the Sebasticook in what became Benton, with Gershom Flagg, Jr., the first postmaster;

— West Clinton, which ran only from March 2, 1833, to Aug. 21, 1834, maybe at Brown’s Corner on the Kennebec, which was also included in Benton;

— East Clinton, opened June 13, 1836, in Clinton Village on the Sebasticook and renamed Clinton on July 2, 1842, as part of the division;

— Pishon’s Ferry, on the Kennebec, from Feb. 6, 1844, to Nov. 11, 1903; and

— Morrison’s Corner, Nov. 24, 1891, to June 25, 1903. Kingsbury said in 1892 that post office was in Martin Jewell’s store, one of several stores at the corner since James Morrison opened the first one “in his house” about 1832.

(Kingsbury listed only three post offices: East Clinton in 1836, becoming Clinton in 1842; North Clinton in 1825, becoming Pishon’s Ferry in 1844; and Morrison’s Corner, established in 1891.)

Clinton’s ferries across the Kennebec

According to Major General Carleton Edward Fisher’s history of Clinton (cited repeatedly in last week’s article), at least at Pishon’s Ferry and perhaps at Noble’s Ferry, too, the ferryboats that crossed the Kennebec River were at first propelled by oars, and were later converted to cable ferries, also known as rope ferries or chain ferries.

A cable ferry is propelled by the river current. It is therefore practical only in stretches of river where the current is steady and strong. Here is how it works, according to Fisher.

A cable is stretched across the river and the ferryboat is attached to it at each end by a tether whose upper fastening can slide along the cable. The end of the boat pointing to the far shore is on a short tether, so it is under the cable. The boat’s other end is on a longer tether so it can drift downstream, putting the boat at an angle to the current.

The ferryman drops a board down the side of the boat to form a version of a keel, against which the current pushes. With the boat and board held at an angle to the current, the current pushes the boat across the river.

At the far bank, it is unloaded; the shorter tether is lengthened and the longer one shortened to reverse the angle; and the current carries the boat back across. Fisher did not say whether the board is on the upstream or downstream side, or whether the ferryman needs to switch sides for the return trip.

The picture of a ferry on the Kennebec in Alma Pierce Robbins’ history of Vassalboro shows a flat boat with two square ends. On it stand two horses pulling a wagon, with someone at the horses’ heads and at least one person in the wagon. This ferryboat has a stubby mast with a small triangular sail.

An explanation of Clifton’s, not Clinton’s name

While researching the Town of Clinton’s name for this article, your writer came across a reference that did not fit with other sources. The on-line Maine an Encyclopedia says the town of Clinton was separated from Jarvis Gore on Aug. 7, 1848, and incorporated as a town named Maine.

The article continues, “The following year, the confusing address ‘Maine, Maine’ was changed apparently in honor of DeWitt Clinton, builder of the Eire [Erie] Canal and New York U.S. Senator, Governor, and Mayor of New York City.”

Wikipedia says explicitly that “the town [of Clinton] is not named for DeWitt Clinton.”

(DeWitt Clinton was a nephew of George Clinton, for whom the Town of Clinton is indeed named, as reported above.)

Your writer found on line a reference to Clifton, Maine, in Penobscot County, set off from Jarvis Gore or “The Gore East of Brewer” and incorporated as the town of Maine on Aug. 7, 1848. The name was changed to Clifton on June 9, 1849.

Main sources

Fisher, Major General Carleton Edward History of Clinton, Maine (1970).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), in Manchester, New Hampshire, congratulates the following students on being named to the Summer 2022 President’s List. The summer terms run from May to August.

Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), in Manchester, New Hampshire, congratulates the following students on being named to the Summer 2022 President’s List. The summer terms run from May to August.