Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Blacks in Maine – Part 2

by Mary Grow

Black Kennebec Valley residents

The first two Black men recorded in Augusta, according to Anthony Douin, one of the contributors to H. H. Price and Gerald Talbot’s Maine’s Visible Black History, were “York Bunker and Cuff.” They were in the garrison at Fort Western, built in 1754, “listed as servants and paid as privates.”

As the area near the fort was settled, Douin found limited evidence of Black residents, and no evidence of Black slaves.

He wrote that at the 1776 town meeting, voters approved taxing “Negroes and Mulatto servants at the same rate as apprentices and minors.” And he referred to several Black families mentioned in Hallowell midwife Martha Ballard’s diary; she delivered at least two of their babies.

After Augusta separated from Hallowell in February 1797, Douin wrote that small numbers of Black residents (five in the 1800 Augusta census) worked in “the few occupations opened to Blacks in the nineteenth century – laborer, barber, house servant, waiter, and hostler.”

By 1850, 55 of Augusta’s about 8,000 people were identified as Black, Douin wrote. One was a mill worker, originally from Tennessee, who had married a Maine woman; others were sailors.

(Douin said that Black sailors “played a role in the rich maritime history of the Kennebec River.” Price and Talbot added that in the 1850 census, Maine’s “maritime industries were combined under stevedores, fisherman, stewards, and shipwrights, which represented more than 50 percent of the black population.” The examples they gave suggest that most lived along the coast, from Portland to Machias.)

Maine Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Weston, Jr. (1782-1872; see the Dec. 10, 2020, The Town Line article on chief justices from Augusta) had a Black servant named Lucretia Crossman from 1820 on. “When she died in 1859, she was buried in the Weston Family Tomb at Cony Cemetery,” Douin wrote.

Three Black men left public records that Douin drew on for profiles.

John D. Carter was an outspoken opponent of slavery whose views were radical enough to split the Augusta Baptists into two churches in the spring of 1844. First Baptist parishioners considered slavery a sin and a violation of human rights. Carter and the rest of the Second Baptists went farther, holding that slave-holders could not be church members or ministers. Carter died July 17, 1844; the churches did not “reconcile” until 1849.

(In his 1870 history of Augusta, James North recorded the schism; he named the radical as J. T. Carter and did not mention his race.)

John Eason (May 14, 1776 – 1879) was a Free Will Baptist who helped build the Augusta church building and preached there when there was no regular preacher. Douin wrote that though “unlettered,” he had an excellent memory; he was called “Parson Eason” because of his sermons.

Levi Foye (May 29, 1799 – 1870) owned “one of the most popular restaurants in Augusta,” his Water Street oyster bar, opened around 1830.

A Massachusetts native whose father brought the family to Vassalboro, Foye’s first profession was as a sailor; during the War of 1812, he was a British prisoner in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His restaurant was successful enough that he was able to buy his family a Western Avenue house.

Among Augusta residents Foye was “well respected,” Douin said; but some of the troops who mustered in Augusta during the Civil War were so disrespectful that Foye closed the restaurant.

“An embarrassed Augusta community hosted a farewell party and presented Foye and his family with a very nice silver service,” Douin wrote.

After the war, Foye reopened the restaurant and ran it until his death.

Douin names two Black men from Augusta who served in the Civil War. Jackson Phillips (born in 1842; later in the book called Phillip Jackson) was a cook on the USS Tallapoosa, launched Feb. 17, 1863, a wooden steamer equipped with heavy guns and howitzers for stopping blockade runners and bombarding shore installations.

Adarastus Brown was in the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, a Black unit that “did garrison duty in Louisiana late in the war.”

The later list of Black Civil War veterans in Maine adds two more Navy men, William H. Lewis and William H. Manuel.

Lewis, according to an online source, served on two ships in the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Through September 1863 he was on the USS Commodore Perry, a former sidewheel ferry. She patrolled the North Carolina and Virginia coasts from January 1862 to the end of the war, helping capture Confederate ships and coastal towns and cities.

From December 31, 1863, through March 31, 1865, Lewis was on the USS Whitehead, a screw steamer built in 1861 that also patrolled off North Carolina.

Manuel first served in 1863, briefly, in USS Sabine, also in the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The Sabine was an 1855 sailing frigate that had seen service off Paraguay before becoming one of the first ships to serve in the Civil war, watching the Florida coast.

By Nov. 18, 1863, Manuel had transferred to the USS Niagara, where he stayed until April 1, 1864.

The Civil War Niagara was the second of that name, built for the Navy in 1855. She had already helped lay the first transatlantic cable in 1857 and 1858; returned Africans rescued from a slave ship to Liberia in 1858; and carried the first Japanese diplomatic delegation to Washington back to Japan in 1860 and 1861. In April 1861 she joined the East Gulf Blockading Squadron off Alabama and Florida.

When northern soldiers came home after the war, Douin wrote that freed slaves who had joined the army sometimes came with them. In Augusta, he said, more than a dozen Black families settled in the area that is now Ganneston Drive (running south off Capitol Street, west of the State House complex); the area was called Nigger Hill.

Douin wrote that their dwellings “were described as log cabins. By 1896 the colony had disappeared, leaving old cellar holes and broken stone fences to mark its existence.”

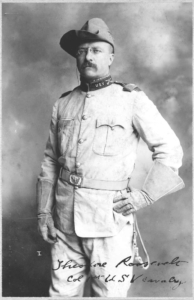

One former slave, Frederick Brown (1835 – 1919), connected with the 15th Maine when Union forces captured New Orleans. Coming to Maine with a captain from Bath, Brown moved to Augusta and got a job with Governor Samuel Cony’s son-in-law, Joseph H. Manley.

Manley was a close friend of James G. Blaine (see the Aug. 20, 2020, issue of The Town Line for a profile of one of Maine’s most famous politicians), and Brown found a new position as Blaine’s coachman, Douin wrote. Through these connections, he became the Augusta post office janitor when Manley was postmaster and later the State House night watchman, serving for 26 years.

Peter Samuel from Virginia was another former slave, who helped guide fellow slaves into Union-held areas before taking himself to safety. Douin wrote that in Augusta, Samuel married a French-Canadian – his first wife had been sold away from him before the war — and converted to Catholicism. He died June 1, 1904, aged 100, “and is buried in a segregated part of Old St. Mary’s Cemetery.”

The website Find a Grave identifies this cemetery as St. Mary of the Assumption Cemetery on the south side of Winthrop Street. Your writer found the “segregated part” is a strip about 12 feet wide on the extreme eastern edge of the cemetery, between the east fence and a one-lane paved road; the Samuels graves are in a north-south line between two large trees.

Many of the inscriptions have become less legible with time. Most of the dates below are from Find a Grave, which lists seven Samuels/Samuells.

The northernmost marker is a small stone for Anna Samuel, 1885-1886 (not listed by Find a Grave). There is a gap; then a twin headstone for Martha (June 14 – Aug. 17, 1893) and Mara (? 1891 – Aug. 16, 1891); a small stone for Rosie Samuell (1887-1896); another gap; a twin stone for Annie (Aug. 18, 1888 – June 1889) and Edie E. (May 20, 1891 – June 22, 1892); and Peter Samuel’s larger stone.

Find a Grave lists a headstone for Henry Samuell (1885-1886) that your writer did not see. South of Peter Samuel’s stone is one marking the grave of Fred, son of Fred? and Sadie Barton, who died July 27, 1911, aged three months and ? days. Find a Grave lists no Bartons in St. Mary’s Cemetery.

* * * * * *

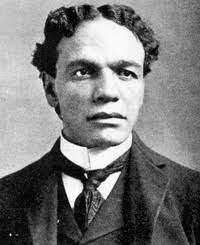

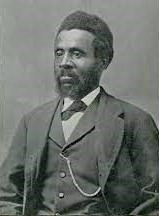

One of Waterville’s best-known Black residents was Samuel Osborne (1833 – July 1, 1904), janitor at Colby College from 1867 until 1903. Known as “Janitor Sam” and as “Professor” because of his appreciation for education and knowledge of the Colby campus, he has been the subject of many articles and a book, Samuel Osborne, Janitor, by Frederick Padelford (Colby 1896).

An on-line People’s History of Colby College says Osborne was born in slavery on a Virginia plantation. He married a fellow slave, Maria Iverson, before the Civil War. In May 1865, Colonel Stephen Fletcher, Colby 1859 and captain of the 7th Maine, helped him come to Waterville, and Colby President James Champlin helped him get a job in the Maine Central Railroad shops.

Two daughters came with Osborne, and in October 1865 Waterville Baptists raised money for him to return to Virginia for his wife, a third daughter and his father, “who had been a slave for seventy-two years.” The father promptly got the janitor’s job at Colby; when he died in 1867, his son quit the railroad and took over at the college.

The Osbornes had one son and seven daughters. Their son Edward “Eddie” Samuel Osborne entered Colby with the class of 1897, but dropped out and went to work for the railroad.

Price and Talbot wrote that Eddie Osborne was a messenger for 56 years for “what became the Railway Express Agency,…logging a million or more miles.” In 1944 he received the Agency’s first “diamond-studded pin” recognizing 50 years of service.

Samuel and Maria’s daughter, Marion Thompson Osborne (later Matheson), born about 1879, was Colby’s first female Black graduate, Class of 1900. (The first male Black graduate was Adam S. Green, Class of 1887.)

In addition to his extensive Colby responsibilities – “everything from keeping fires burning in all fireplaces to delivering the mail” – Osborne was active in the Waterville Baptist Church and in the Waterville Lodge of Good Templars, the national temperance organization.

Marion Matheson’s 1950 tribute to her father, excerpted in Price and Talbot’s book, includes anecdotes from her father’s life. One is a summary of his 1902 trip to Stockholm, Sweden, as a Good Templars delegate to an international convention. On the voyage over and back, he ate at the ship captain’s table; in Stockholm he was granted permission to sit on the royal throne; and he took a side trip to Scotland to visit former Waterville residents.

When he fell ill, Matheson wrote, college President Charles Lincoln White in his 1904 Baccalaureate address called him, “the Head Janitor whom all had learned to love and respect for his faithfulness and devotion to the interest of the college, of his gentle, warm and confiding nature because he cared for the sick, chided and erring and encouraged all by his simple, pure, and unaffected Christian life.”

The day of his death was “an incredibly sorrowful day for Colby,” the People’s History says. President White was at his bedside until the end. The college bell tolled 71 times. Matheson wrote that his funeral was the first one “held in the Chapel in Memorial Hall, as was his wish.”

An article in the 2018 issue of the Colby Echo, found on line, says Osborne was the subject of “vicious and despicable racism” and was not paid enough to support his family. The author is Alison Levitt, identified on line as the college’s Online & Social Media Editor.

The People’s History does not totally contradict Levitt’s portrait. The author wrote that Osborne “tirelessly endured their [students’] pranks and assaults on his intelligence” – and stood up for them when they got in trouble with faculty or administration members and joined Maria in inviting them for Thanksgiving dinners.

The author agreed that Osborne was not paid generously. In 1896, after 29 years on the job, he earned $480. Meanwhile, the college had grown from three buildings in 1867 to (by 1903 when he retired) seven buildings.

(These buildings were on the old campus by the Kennebec River; the college did not begin the move to Mayflower Hill until the 1930s. The People’s History writer said Colby had only one full-time janitor for “several decades” after Osborne’s retirement.)

Samuel and Maria Osborne and some of their children are buried in the family plot in Waterville’s Pine Grove Cemetery.

Main sources

Price, H. H., and Talbot, Gerald E., Maine’s Visible Black History: The First Chronicle of Its People (2006)

Websites, miscellaneous.

by Jim Metcalf

by Jim Metcalf