Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Waterville historic district – Part 2

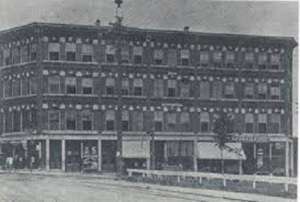

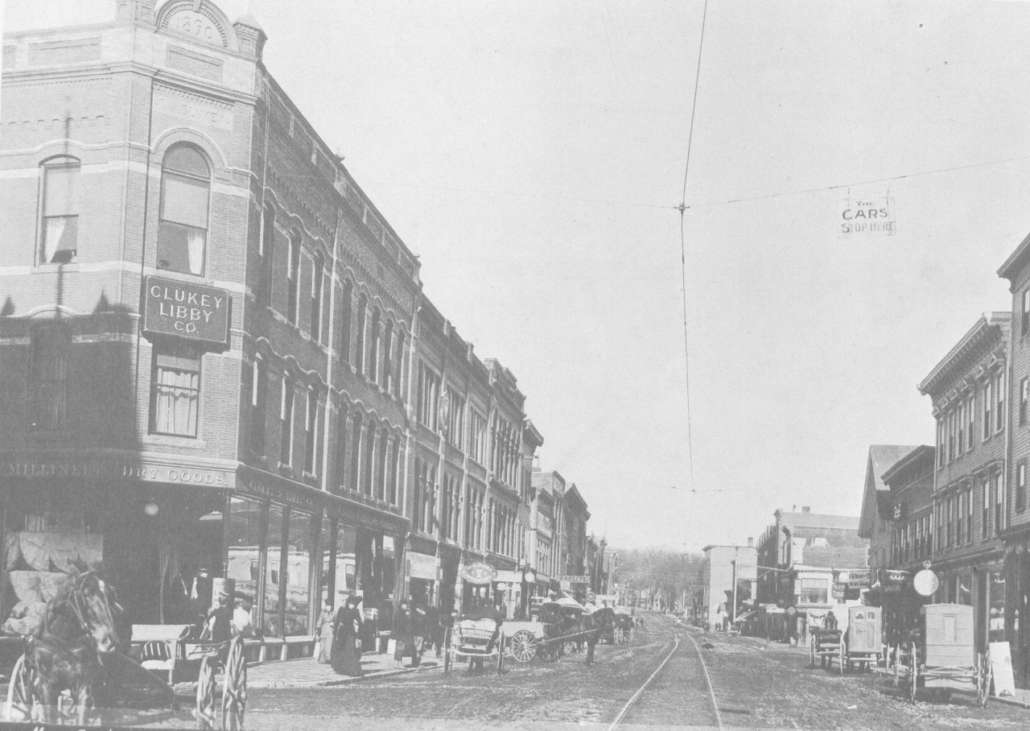

The Clukey Building, located on the corner of Main and Silver streets, location of the Paragon Shop today.

by Mary Grow

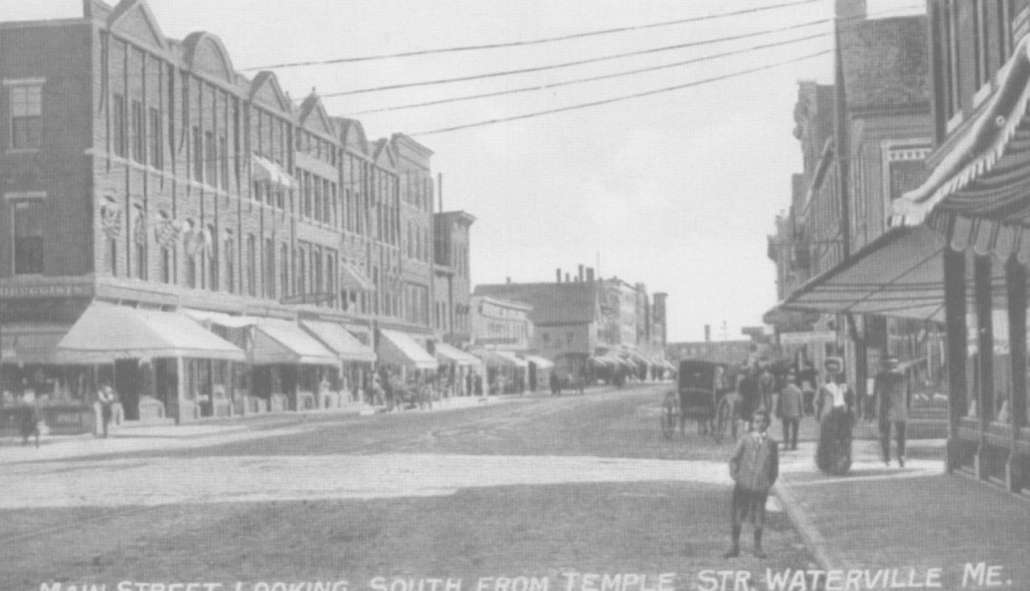

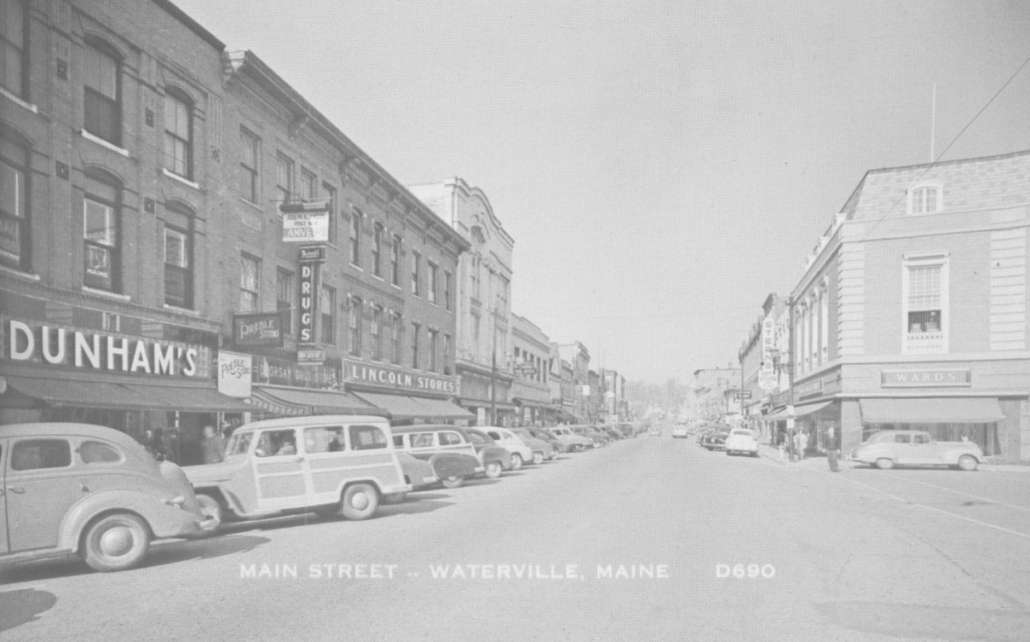

This week’s description of Waterville’s Main Street Historic District begins where last week’s left off, with the Common Street buildings on the south side of Castonguay Square, and continues down the east side of Main Street. It adds a summary of the separate Lockwood Mill Historic District, across the intersection of Spring and Bridge streets at the north end of Water Street (see also the May 7, 2020, issue of The Town Line.)

* * * * * *

Continuing with Matthew Corbett and Scott Hanson’s 2012 application for the Waterville downtown historic district, on the south side of Common Street, the building at the east end (closest to Water Street) is the brick Haines Building at 6-12 Common Street. Built four stories tall in 1897, after a 1942 fire destroyed the top three stories only one was rebuilt.

Next west is the 1890 “Romanesque Revival style Masonic Block,” a four-story brick and granite building. Adjoining it is the three-story Gallert Block, which the application says was built in 1912 to replace wooden stores that had burned in 1911. Corbett and Hanson describe it as blonde brick with granite and brick trim and an example of Commercial Style architecture.

The building on the corner of Common and Main streets is the Krutzky Block (57-59 Main Street), also built a year or so after the 1911 fire. The building “combines elements of the Arts and Crafts and the Spanish Colonial Revival styles.” The façade has two bays that face Common Street; four bays that “begin to turn toward Main Street”; a single narrow bay with the main entrance facing “the corner of Common and Main Streets”; and two bays on Main Street.

Materials in this building include stucco, stone, metals and brick. The brick is “laid in Flemish bond which provides a subtle pattern to the brickwork.”

The next two properties south, the GHM Insurance Company building and the pocket park, are post-1968, too new to count as historic.

Next south of the park, the 1936 three-story Federal Trust Company Bank building at 25-33 Main Street was designed by architects Bunker & Savage, of Augusta, in Art Deco style, the only Art Deco building in the district that was designated in 2012. The original part on the north end “is of limestone construction with later expansions in stone or ceramic tiles and stucco with varied marble and brick storefronts,” Corbett and Hanson wrote.

The bank later absorbed two buildings south, a 19th-century brick one and an undated section, also brick, taken over from the Levine Building. The application says the southern building dated from the early 19th century and “appears to have been a two story brick block with granite piers and lintels at the storefront level and a side gable roof.” By 1875, it was three stories high.

The Levine’s Clothing building dated from 1880. Four stories, brick, it was remodeled in 1905 and again in 1910 before being demolished recently to make room for Colby College’s Lockwood Hotel.

Corbett and Hanson name the hotel on the Levine building’s upper floors the (earlier) Lockwood Hotel. Frank Redington’s chapter on businesses in Whittemore’s history calls the southernmost “pretentious building” on the east side of the street the R. B. Dunn Block, with the Bay View Hotel above the street-level store. The Town Line editor Roland Hallee wrote that the Levine building “expanded in the 1960s to the site of the former Crescent Hotel,” on the then-existing traffic circle at the foot of Main Street. (See the June 9, 2022, issue of The Town Line for Hallee’s memories of Levine’s in the 20th century.)

The historic district application describes the building at 9-11 Main Street as separate from, but by 2012 part of, Levine’s. Built before 1875 as “a two-bay, two-story Italianate style brick commercial building,” it acquired a “third story and new cornice” between 1889 and 1894, “apparently as part of change of use from a grocery store to small restaurant and saloon.”

Your writer and Hallee both remember the Silver Dollar tavern, which Hallee locates overlooking the Kennebec River on the east side of the traffic circle. Whether the Silver Dollar is the “saloon” Corbett and Hanson mentioned is not clear. Hallee wrote that the tavern building was demolished when the rotary was eliminated.

* * * * * *

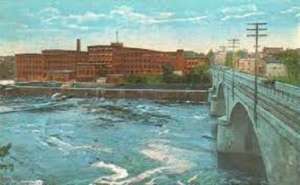

The Lockwood Mill Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 8, 2007. The application was completed in January 2007 by Roger G. Reed, an architectural historian with the Portland architectural firm of Barba and Wheelock, and Christi A. Mitchell, of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

The district at “6, 6B, 8, 10 and 10B Water Street” includes three large mill buildings numbered 1, 2 and 3; a 1918 power house and the “Canal Headworks/Forebay Canal”; and a power house too new to count as contributing to the historic value.

Reed and Mitchell’s summary calls it a “complex of brick textile factory buildings and associated water-retaining and hydro-electric generating structures”; and “the only major nineteenth century textile complex constructed in Waterville.”

The three main buildings “represent all the surviving buildings associated with the textile factory except for the Lockwood gasometer building on the west side of Water Street,” too much changed to be included.

The northern building, Number 1, has a long extension northward (once called the Picker Building) paralleling the canal and the Kennebec River and a wheelhouse on its east end. Since 1883, Number 1 has been connected to the central building, Number 3. Number 2 stands alone parallel to the other two.

Prominent Rhode Island industrial designer Amos DeForest Lockwood (Oct. 30, 1811 – Jan. 16, 1884) designed the buildings and machinery, and, since local financiers had no expertise in the textile industry, provided essential financial advice as well.

Reed and Mitchell wrote that Mill Number 1 was started in 1873 – the Hallowell granite cornerstone was laid Oct. 17 — and finished in 1875; the wheelhouse gained a second floor in the first decade of the 20th century, and there were alterations in 1958. Mill Number 2 dates from 1881-82, with alterations in 1957. The middle of Mill Number 3 was built in 1883; the structure was extended westward in 1889 and eastward in 1894 and extensively modified in 1957 and 1958.

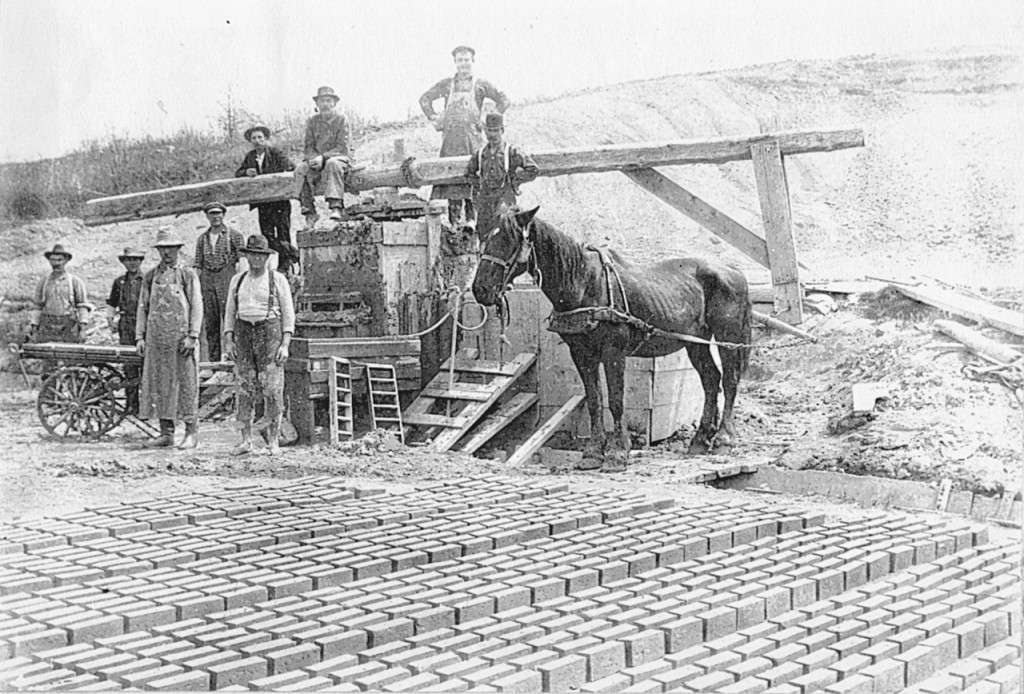

Described as brick buildings on granite foundations with granite trim, their architectural style is listed as Late Victorian/Italianate. Reed and Mitchell found that the brick was made in a brickyard in Winslow; the granite came from the famous Hallowell quarries.

The builders provided granite windowsills, and inset the windows and spandrels one brick deep, “creating the appearance of pilasters running the full height of the buildings.” The reason, the application explains, was that Lockwood wanted large windows for maximum natural light, but needed thick walls to withstand the stress caused by the vibrating machinery.

(Spandrels are the near-triangular corners between the tops of arches and the surrounding frame. Pilasters are vertical ornamental columns on walls that look like supports, but are only decorations.)

The application quotes the local newspaper writing in 1874 that Waterville’s large French-Canadian population (21 percent in 1880, 44 percent in 1900, Reed and Mitchell found) provided a good labor supply.

“The construction of a new city hall and opera house in 1901 and a Carnegie library in 1902 were symbolic of the prosperity initiated in large part by the Lockwood Mill,” Reed and Mitchell wrote.

Henry D. Kingsbury, describing mill operations in 1892, wrote that by then $1.8 million had been invested. In the first half of the year, he wrote, the Lockwood Company produced “8,752,682 yards of cotton cloth, weighing 2,978.000 pounds.” Twelve hundred and fifty people worked 10 hours each weekday at the looms and spindles; 50 to 75 “skilled mechanics” were “constantly employed, capable of reconstructing any machinery in use.”

Mill Number 1 is about 70 feet wide and four stories tall, with a five-story tower in the middle of the south side. The tower did not mark the main entrance, Reed and Mitchel found; it was called the “back tower” on early plans, and the mill office, which they imply was the main entrance, was “on the north side facing Water Street.”

The tower housed the freight elevator and bathrooms.

Three curving wooden staircases in the main building were surviving in 2007. They were enclosed between the outside walls and interior walls that also housed sprinkler pipes.

Here is Reed and Mitchell’s description of the interior of the main part of Mill Number 1: “the basement sections (separated by brick fire walls) were allocated for weaving, the storage of mill supplies, and carpentry and machine shop. The first floor was allocated for weaving, the second floor for spinning, the third floor for carding and warping, and the fourth floor for sizing, spooling and spinning.”

The building remained a textile mill until around 1979.

Mill Number 2, the southernmost building, is the largest, about 100 feet wide and in its main section five stories high. It had on the east a “four story wheel house and harness shop” and on the west a four-story wing with a one-story addition on the south. There were “two brick entrance vestibules on the north side.”

Reed and Mitchell wrote that the single-story wing was much changed, both outside (windows and entrance) and inside, in 1957, when it became the C. F. Hathaway Shirt Company. The new entrance and its surroundings were Colonial Revival style. Inside, the building acquired elevators and part of the open space was partitioned to make offices, a third-floor cafeteria and other rooms.

Mill Number 3, dating from 1883, was between and parallel to the other two buildings, and in its early life connected to each at the second-floor level. Of the same original style and materials, it was the most extensively changed in the 1950s.

Reed and Mitchell wrote that the original use was “packing, boiling, rolling and folding on the first floor, and weaving on the second floor.” The extensions in 1889 and 1894 provided more room for weaving.

After Central Maine Power Company moved into the building in 1958, the “brick shell” remained, with replacement doors and windows and “major interior alterations.”

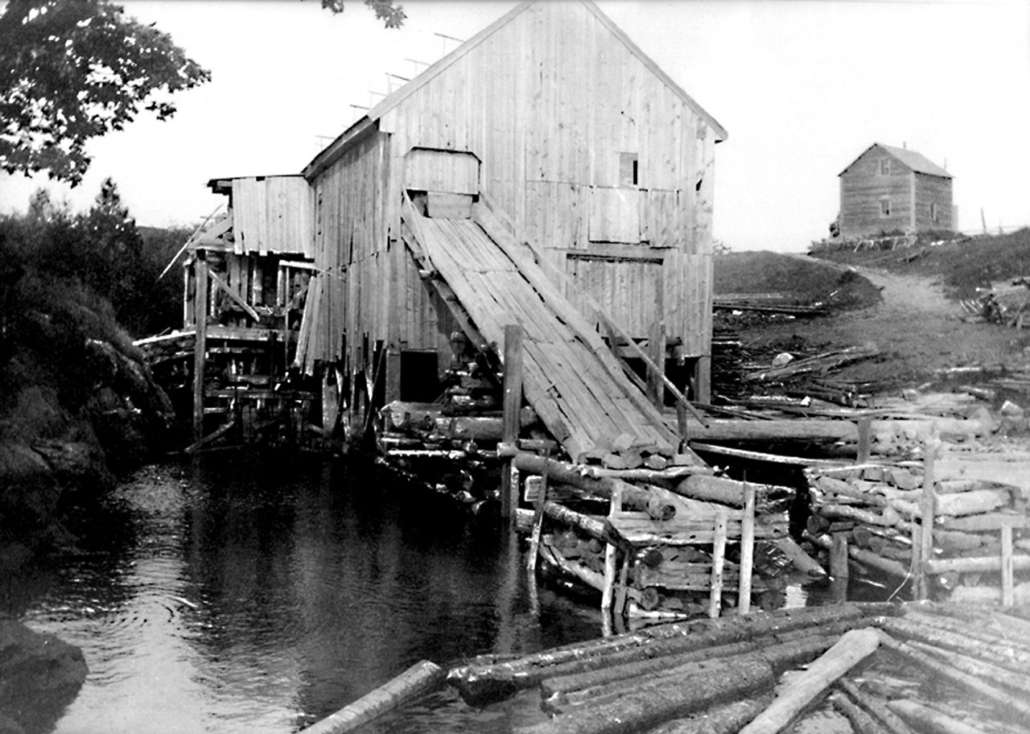

Reed and Mitchell’s application includes descriptions of the canal, replacing earlier wooden cribbing “to channel the water and power the mill,” and the associated Lockwood Powerhouse. The concrete powerhouse, through which water runs “through turbines to power the generators,” is in two sections. The larger north side is open from top to bottom; the south side has “a mezzanine with two floors of rooms.”

* * * * * *

The Hathaway Shirt Company deserves a section of its own, but, as usual, your writer has run out of space. As Vassalboro School Superintendent Alan Pfeiffer often says, “Stay tuned.”

Main sources

Corbett, Matthew, and Scott Hanson, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Waterville Main Street Historic District, Aug. 28, 2012, supplied by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892, (1892).

Reed, Roger G., and Christi A. Mitchell, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Lockwood Mill Historic District Jan. 11, 2007.

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.