Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Native Americans – Part 3

by Mary Grow

Three local settlements

The Kennebec tribe’s village at Cushnoc (a word that means head of tide, most historians agree) was on high ground on the east bank of the Kennebec River in what is now Augusta, about 20 miles south Ticonic village (described last week).

Leon Cranmer, in his Cushnoc, pointed out that the high land provided views of river traffic both upstream and down and offered some protection against attack. Canoes could land in a cove at the foot of the bank (now, he wrote, a park and boat landing).

Charles E. Nash, in his chapters on Augusta in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, wrote that Cushnoc village had wigwams, cultivated cornfields and open space for young men to practice “wrestling, running and dancing.”

Kerry Hardy, in a nicely-illustrated 2009 book titled Notes on a Lost Flute: A Field Guide to the Wabanaki, argued that Cushnoc was the west end of an important Native American trail that ran from the present town of Stockton Springs near the mouth of the Penobscot River (almost due east of Cushnoc) to the head of tide on the Kennebec River.

Looking at old maps, Hardy traced that east-west trail and found others that converged on Cushnoc, coming from present-day Rockland (on the coast to the southeast), Canton Point (on the Androscoggin River to the northwest) and Farmington Falls (on the Sandy River to the north).

Unfortunately, Hardy did not explain why Cushnoc was the center of a Native American communications network. Instead, he summarized the importance of the British trading post established there (as at Ticonic; and, as at Ticonic, the site of the trading post was later chosen for a fort).

Cranmer offered the theory that Cushnoc was a convenient mid-way place for Native Americans traveling between Canada and the coast to branch off to other parts of Maine.

During archaeological excavations around the trading post site between 1974 and 1987, Cranmer wrote, more than 17,500 artifacts were found, mostly signs of European rather than Native American habitation.

He specifically mentioned a few stone flakes left over as Kennebecs made their edged tools; a stone projectile point that appears from its photograph to be in excellent condition and could be anywhere from 2,200 to 6,000 years old; and a bit of pottery, the remains of what Cranmer called an Iroquoian-like jug or bowl.

If there was a Native American burial ground associated with Cushnoc, this writer has been unable to find a reference to it. J. W. Hanson, in an 1852 history of the area found on line, claimed that “the quiet graves of their [Kennebec tribal members’] fathers clustered around the mouth of each tributary to their beloved river,” but he offered no specific location.

The first British trader at Cushnoc was Edward Winslow from the Plymouth Colony in 1625, Nash wrote (or in 1628, according to Old Fort Western Director Linda Novak’s bicentennial lecture). He and successors traded European goods for Native American products, primarily beaver skins.

By the 1650s, trade and profits were diminishing, Nash said. In 1661 the Plymouth group sold the trading post to four other Europeans, who gave up and closed the operation about 1665.

Novak blamed the decline in trade at Cushnoc on rival traders Thomas Clark and Thomas Lake, who opened competing posts both upriver at Ticonic and downriver near current Pittston. James W. North, in his history of Augusta, blamed “growing Indian troubles” for the decline and said war was the final blow (the first war counted by historians, writing primarily from the Anglo-American point of view, started in 1675).

North listed other problems in the 1650s, including a decrease in fur-bearing animals, the Kennebecs’ recognition that the furs were more valuable than the goods offered in exchange and “the increasing number and avaricious disposition of the traders.”

Cranmer added two more problems that could have contributed to a smaller supply of furs: British settlements expanding into woodlands, and attacks on Maine Native Americans by Iroquois tribes from the northwest (current upstate New York and thereabouts).

In 1655, the governor of the Plymouth Colony appointed Captain Constant Southworth as magistrate at Cushnoc, responsible for administering civil law throughout the colony’s holdings. He had two main jobs, Nash wrote: to prevent other traders from trespassing and “to check the sale of demoralizing liquors to the Indians.”

Nash commented that Joseph Beane or Bane, an Englishman held captive by the Native Americans, reported that remains of the Cushnoc trading post were still visible “among the new-grown trees and shrubbery” in 1692. Novak, however, says the post was burned in 1676, during the first of the serial wars. Either account suggests the Kennebecs had no interest in using the building.

North wrote that the 1725-1744 interregnum in the Kennebec Valley wars was a genuine peace, during which the Kennebecs interacted peacefully with the British traders, who he suggested treated them fairly and even generously, and with early settlers. In 1732, Massachusetts Governor Jonathan Belcher and “a large retinue” toured the coastal settlements. The governor met with an unspecified group of Native Americans at Falmouth, and told them that he planned to establish three missionary stations in the province, one to be at Cushnoc, “where a town and church were about to be built.”

North offered no evidence of such a town, or of any pacifying influence from missionaries, before the final defeat of the French at Québec in 1759. Instead, continued Native American resistance delayed the growth of European settlements around Cushnoc for another generation.

* * * * * *

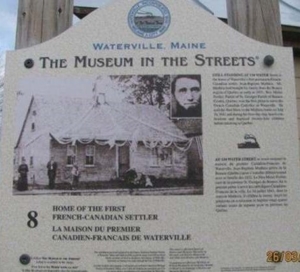

Besides the settlements at Ticonic/Winslow and Cushnoc/Augusta, Kennebec tribal members lived elsewhere along the Kennebec River, its tributaries and other nearby water bodies. Some of the town histories on which this writer relies describe evidences of pre-European occupation from Fairfield and Benton through Waterville/Winslow and Vassalboro/Sidney to Augusta.

The current Town of Benton has frontage on the Kennebec River, and the Sebasticook River runs (almost) north-south through (almost) the middle of town. The Sebasticook, like the Kennebec, was a major travel route for Native Americans.

Benton historian Barbara Warren says because of the rapids in the Kennebec above Ticonic (until Waterville manufacturers’ dams calmed them, beginning in 1792), upriver travel was via the Sebasticook to Benton Falls, about five miles upstream from the Kennebec, and a portage back to the Kennebec at Fairfield. The Sebasticook was also a connector between the Kennebec and Penobscot valleys, according to another source.

Kingsbury wrote that “the relics found many years ago at the foot of the hill overlooking Benton Falls are now the only traces of the original possessors of the soil.” The “hill” – high land – is the east bank of the river where Garland Road runs through Benton Falls Village. Warren remembers as a child walking along the river and finding artifacts like shards, grinding tools and “a stone weight for a fishing net.”

Warren says a state-listed archaeological site on the west side of the Sebasticook near the dam includes a burial ground. State preservation officials are protecting the exact location of the site. Your writer surmises there was a Kennebec village, at least seasonally for fishing and perhaps year-round for farming and hunting, on the east bank with the burial ground across the river, as at Ticonic.

A 1992 University of Maine at Farmington study of the banks of the lower Sebasticook, between the dams at Benton Falls and Fort Halifax, found 30 archaeological sites along that part of the river, dating from the Archaic period (in Maine, between 10,000 and 3,000 years ago, according to Wikipedia) and the early contact period in the 1600s.

A 2004 archaeological survey related to the Unity Wetlands covered the banks of the Sebasticook in Unity and a small part of Benton and found 16 riverside Native American sites. Ten of the sites were either near rapids or near a junction with a tributary stream.

In the 2004 study, the site at Benton Falls was described as having been used during the Archaic and Ceramic periods. Wikipedia says in Maine, the Ceramic period was between 3,000 and 500 years ago, or from about 1000 B.C. to about 1500 A.D.

Both the Farmington study and a Biodiversity Research Institute publication by C. R. DeSorbo and J. Brockway, found on line, mention pre-European fisheries for migrating river herring. Warren says there is evidence suggesting Native Americans built a two-tier stone fish trap where Outlet Stream from China Lake runs into the Sebasticook in Winslow, within a mile of the Kennebec.

In neither Benton nor Fairfield are there well-known evidences of pre-European settlement along the Kennebec. The Fairfield bicentennial history says Native Americans made arrowheads in an area called the sand hills in Larone, in northern Fairfield. Evidence cited included arrowheads, broken and unbroken, and chips from making the arrowheads (although collectors had picked up most of the chips).

The type of rock used to make the arrowheads was not found locally, the writers said. They surmised the Native Americans brought the rock from Moosehead.

In Alice Hammond’s 1992 history of the Town of Sidney, she quoted Dr. Arthur Speiss, of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, saying there had been Native Americans in Sidney since “at least 5,000 years ago.” By 1992, Hammond wrote, the Historic Preservation Commission had found 11 pre-European sites along the Kennebec River and eight along Messalonskee Lake’s eastern shore.

The Town of Sidney’s 2003 comprehensive plan gives the number of pre-historic sites as 23. Maps show four areas along the Kennebec and three more on Messalonskee Lake. The plan explains that the exact locations are not publicized to protect the areas.

Hammond wrote that there was no valid way to estimate how many Native Americans lived in Sidney, nor are there individuals’ names or information on when the last groups left. She surmised they could have been gone by the 1740s.

Sidney does, however, have its legend, retold in Hammond’s history and in other sources, including Maine Indians in History and Legend.

According to that version, Messalonskee Lake is named from the Native American word “Muskalog,” or “Giant Pike,” a big, voracious fish that lived in the lake. The name further recognizes that 14 other water bodies empty into the lake, “which like the Giant Pike was never satisfied.”

A heroic brave named Black Hawk and a sneaky brave named Red Wolf both loved a lovely, lively maiden named White Fawn. White Fawn chose Black Hawk.

The evening they were formally engaged, White Fawn and Black Hawk stole away from the celebration for some private moments on a clifftop overlooking Messalonskee Lake. Red Wolf followed them, killed Black Hawk, whose body fell into the lake, and tried to kidnap White Fawn.

Screaming, she jumped from the cliff into the water. The rest of the tribe rushed to the scene. Red Wolf cried out “Messalonskee! Messalonskee!” As the avengers closed in on him, there was an earthquake and an avalanche swept him, too, into the ever-hungry lake.

Series of lectures available online

A series of 10 lectures on early Maine history presented at Old Fort Western in 2021 is now available for viewing on line. Topics include Native Americans, Fort Western and Fort Halifax and trading posts on the Kennebec River. Speakers include Dr. Arthur Speiss and Leon Cranmer, mentioned in this article. The series can be found by searching for Old Fort Western or Maine bicentennial lectures.

Main sources

Cranmer, Leon E., Cushnoc: The History and Archaeology of Plymouth Colony Traders on the Kennebec (1990).

DeSorbo, C. R. and J. Brockway, The Lower Sebasticook River: A landowner’s guide for supporting one of Maine’s most unique and important ecosystems. (2018).

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Hardy, Kerry, Notes on a Lost Flute: A Field Guide to the Wabanaki (2009).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Maine Writers Research Club, Maine Indians in History and Legends (1952).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Warren, Barbara, email exchange.

Websites, miscellaneous.