Grand Army of the Republic hat insignia worn by the Horse soldiers.

GAR posts Fairfield, Windsor, China, Albion & Sidney

Continuing with central Kennebec Valley GAR Posts in the order of their formation, the next after Billings Post #88, in Clinton, was Fairfield’s E. P. Pratt Post #90 (in Somerset County, therefore not on the Kennebec County list in Henry Kingsbury’s history). According to Barbara Gunvaldsen, of the Fairfield Historical Society, this Post was organized Oct. 18, 1883.

Records at the FHS History House (the 1894 Cotton-Smith House) include a summary biography of Elbridge P. Pratt, in whose honor the Post is named. He was born in 1841, son of a farmer, Jesse Pratt, and his wife Hannah (Hubbard) Pratt.

On July 23, 1862, Pratt enlisted in Fairfield; he was mustered in July 25 (Wikipedia says Aug. 25) in Bath as a private in the 19th Maine Infantry, for three years. On July 27, his unit went to Washington, where it was stationed until September 1862. In October, the 19th was assigned to the Army of the Potomac.

Battles in which the 19th fought included Fredericksburg, Virginia (Dec. 11-15, 1862); Chancellorsville, Virginia (April 30 – May 6, 1863); and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (July 1-3, 1863).

Pratt was killed on July 2, 1863, one of 232 men – more than half the regiment’s total – the 19th lost at Gettysburg. He is buried in Gettysburg National Cemetery.

E. P. Pratt GAR Post was still active in early 1918. A paragraph in the Tuesday, Jan. 10, 1918, issue of the Fairfield Journal announced the Wednesday, Jan. 16 (either day or date must be a misprint) installation of officers of the E. P. Pratt Relief Corps (the GAR ladies’ auxiliary) at the GAR Hall. Post members and wives, Corps members’ husbands and Sons of Veterans and their wives were invited.

* * * * * *

South China’s James Parnell (or Parnel) Jones Post #106 was organized April 23, 1884, with 25 charter members, Kingsbury said. At first members met in the AOUW (Ancient Order of United Workmen) hall; in 1885, according to the China bicentennial history, they built their own hall (demolished in 1964) at the crossroads where South China’s Memorial Park now stands.

Kingsbury said the GAR building was “complete in itself, containing a large hall, offices, rooms for Sons of Veterans and a Woman’s Relief Corps, and suitable banquet hall.”

Major James Parnell Jones (May 21, 1835 – July 12, 1864) is locally famous as “the Fighting Quaker.” Born in China, son of Quaker missionaries Eli and Sybil Jones, he was educated at the State University of Michigan and Haverford College, Pennsylvania.

On Sept. 15, 1857, he married Rebecca Maria Runnels (1836 – April 14, 1899).

When the Civil War began in April 1861, Jones was principal of China Academy, in China Village. He and Rebecca had lost their first son, James Lecky, in 1859, at the age of six months; their second, James A. “Jamie,” had been born Feb. 16, 1861. Nonetheless, Jones promptly helped raise and became captain of the unit that became Company B, 7th Maine Infantry.

In September 1862 he was slightly wounded. In 1863, he was promoted to major. In 1864 he was wounded again, at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7); and on July 12, 1864, he was killed at Crystal Springs, Virginia, outside Washington D. C.

Sometime in 1863 Jones had home leave, because his and Rebecca’s daughter, Alice, was born Aug. 6, 1864. She lived five days, dying on Aug. 11; and on Aug. 14, three-year-old Jamie died.

Parents and children are buried in China’s Dudley Cemetery, on Dirigo Road, with James P. Jones’ mother, Sybil. His father Eli’s grave is in the nearby Dirigo Friends Cemetery.

Rebecca remarried on Sept. 29, 1867, to Rev. Moses W. Newbert.

An undated obituary from the Lincoln County News says Newbert was born in Waldoboro and died May 6, 1898; the accompanying picture of his tombstone shows he was aged “64 yrs. 3 mos. 14 dys.” The obituary writer praised his “natural ability” as a preacher and said, “His success in the ministry was remarkable.”

The obituary says he began preaching about 1856 “under the direction of the Methodist Conference.” Starting in Palermo, he moved to North Vassalboro, China and Southport; to Wisconsin for two years; and back east to serve in several Maine towns, including Waldoboro.

A period of ill health led to a change to an unspecified 15-year “business career…in China and Camden.” He then returned to the ministry, with posts in “Cushing, Caribou, Hodgdon and Linneus, Sprague’s Mills.” Ill health led to retirement to a farm in China for his last two years, the obituary says.

Newbert’s first wife was Helen Augusta Washburn (Oct. 6, 1829 – May 11, 1866), daughter of Zebah and Susan Washburn of China; they were married March 6, 1860. Newbert is buried in Zebah Washburn’s family plot in the China Village Cemetery.

The newspaper obituary says his second wife was “Mrs. Maria R. Jones, of China, whose first husband was Maj. Jones, who was killed during the war of the Rebellion.” A Methodist yearbook found in line adds that in his last years Newbert was “tenderly cared for by his faithful and devoted wife.”

* * * * * *

Grand Army of the Republic badge.

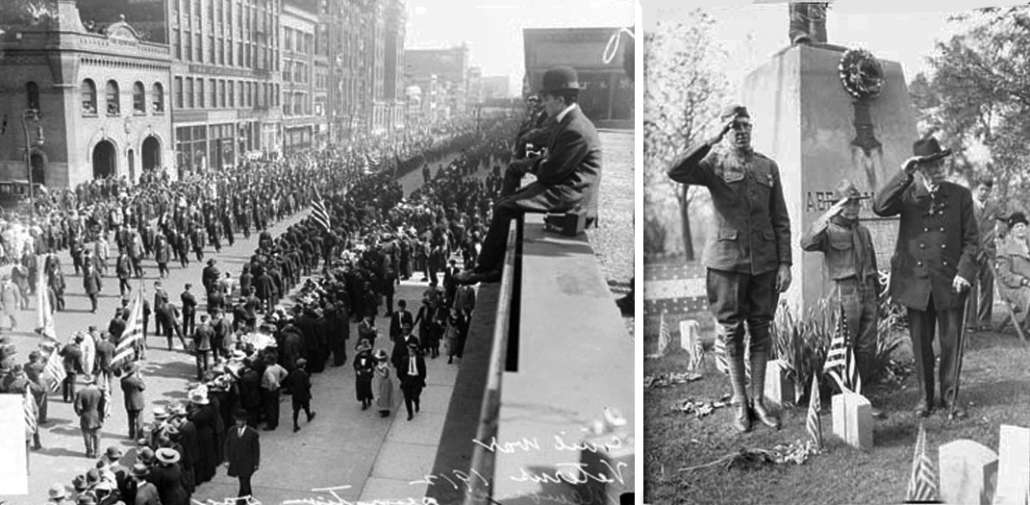

In her research into the history of Albion, Ruby Crosby Wiggin found that Albion’s first Memorial Day observance was in 1885. She wrote that Civil War veterans from Albion and adjoining China organized Grand Army Amos J. Billings Post #112 on May 17, 1884, in China Village.

Kingsbury gave June 17 as the date and said there were 20 original members.

The two towns jointly financed the 1885 Memorial Day celebration, with Albion’s March 1885 town meeting raising $25 for the holiday observance and for decorating solders’ grave.

Kingsbury listed commanders of this Post as Llewellyn Libbey, John Motley, B. P. Tilton, J. W. Brown, Henry C. Rice, Robert C. Brann, A. B. Fletcher and John Motley.

Amos Judson Billings was born Jan. 20, 1833, to Benjamin Allen Billings (1799-1870) and Sarah (Tenney) Billings (1801-1882). On May 1, 1853, in Waldo, he married a woman named Bacon, perhaps Elizabeth A. Bacon (the on-line census record is unsure).

Billings rose to the rank of lieutenant in Company G, 24th Maine Infantry. Census and town records agree that he died of disease in Arkansas on July 28, 1863. His grave is in Albion’s Libby Hill Cemetery.

* * * * * *

Sidney’s Joseph W. Lincoln Post #113 honors Lieutenant Joseph Warren Lincoln, who was born in 1835 and died at Falmouth Virginia, April 8, 1863. His gravestone in the Lincoln Cemetery on Quaker Road says he served in Company F of the 20th Maine; a GAR note on the Find a Grave website, dated 2016 (after the GAR ceased to exist), says Company I, 20th Maine.

In 1857, according to Find a Grave, Lincoln married Laura Ann Whitman McPeak (Jan. 4, 1837 – Sept. 20, 1869). Born in Douglas, Massachusetts, she died in St. Louis, Missouri.

The Sidney Post first met May 24, 1884, according to Kingsbury. Starting with 11 charter members, it had 26 members in 1892.

Meetings were held in the Grange Hall, Kingsbury wrote; GAR members had “contributed considerable labor” to help build it. In her 1992 history of Sidney, Alice Hammond said meetings of both the Post and the Women’s Relief Corps were “in the Town Hall for many years.”

Kingsbury’s list of Post commanders included, in order, Nathan A. Benson, A. M. Sawtell, Thomas S. Benson, John B. Sawtell, Simon C. Hastings, James H. Bean, Silas N. Waite and Gorham K. Hastings. Hammond said Bean was in charge for many years, and his wife, Vileda Bean, was the longest-serving president of the women’s auxiliary. Kingsbury listed Vileda A. Bean among charter members when the Women’s Relief Corps was organized July 29, 1890.

* * * * * *

Windsor’s Marcellus Vining GAR Post honors Lieutenant Marcellus Vining (May 2, 1842 – May 19, 1864).

Kingsbury wrote that Marcellus Vining was the grandson of Jonathan Vining, who came from Alna to Windsor about 1805, and son of Daniel Vining (April 27, 1810 – Feb. 10, 1890). A farmer, Daniel had 12 or 13 children by two wives; Marcellus was his oldest son by his first wife, Sarah Esterbrook (or Esterbrooks) of Oldtown.

Marcellus Vining became a private in the 7th Maine Infantry on Jan. 25, 1862. Kingsbury wrote that the 19-year-old’s “ability and courage soon pointed him out as one especially fitted to a more important place among his comrades.”

Vining received two promotions before his two-year enlistment ended. When he reenlisted Jan. 4, 1864, it was as a sergeant in Company F of the 7th Maine.

He was promoted twice more that spring, to second lieutenant, Company A, on March 9 and to first lieutenant, Company A, on April 21. Wounded at the May 12, 1864, Battle of Spottsylvania, Virginia, he died May 19 in Fredericksburg, before, Kingsbury said, receiving the federal government’s notice that he had been promoted to captain. He is buried in Windsor Neck Cemetery.

Kingsbury wrote that as Vining awaited death, he wrote his father a letter in which he said that “it was preferable for him to die in the defense of his country’s flag than live to see it disgraced.”

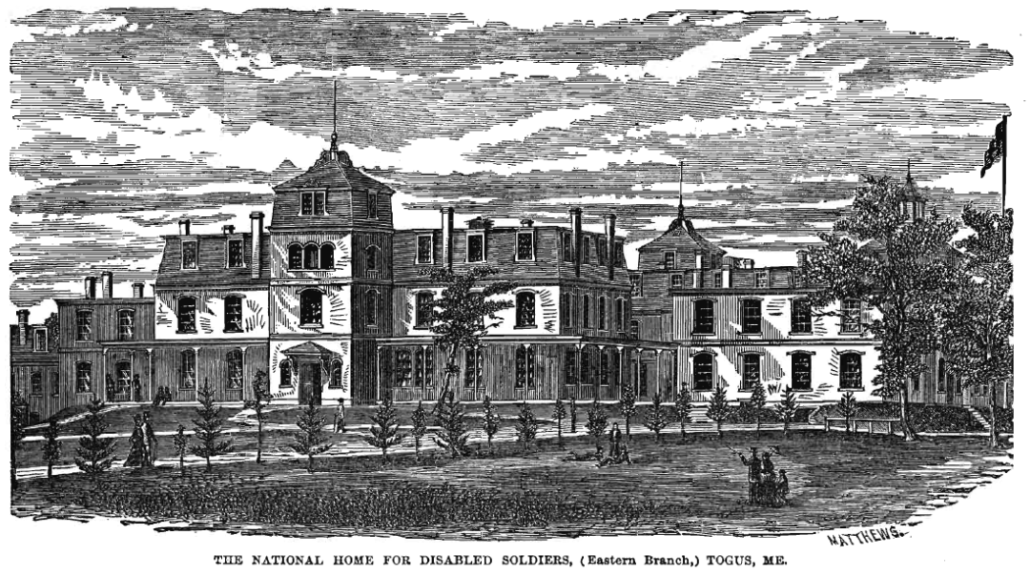

Vining GAR Post #107 was organized June 2, 1884, Kingsbury said. Before then, Lowden wrote, residents celebrated Decoration Day at the National Soldiers Home in Togus.

Kingsbury listed the Post commanders, to 1892, as H. A. N. Dutton, Francisco Colburn, George E. Stickney, G. L. Marson, Cyrus S. Noyes and Luther B. Jennings.

Lowden said Windsor’s Post members met every Saturday night in the GAR Hall, the second floor of the town house. The Hall accumulated memorabilia; Lowden wrote that in 1886, “a Mr. Bangs presented a picture of Marcellus Vining,” and Kingsbury added that the Vining family donated Marcellus Vining’s army sword, a life-size portrait and a flag.

Lowden believed Vining Post continued “well into the twentieth century.” Windsor voters helped fund the organization, usually at $15 a year, he wrote. In 1929, however, “$30.00 was appropriated for G.A.R. Memorial and paid to the Sons of Veterans,” the successor organization to the GAR.

After local Memorial Day observances began, they typically included a speech, Lowden said. Windsor’s first was in 1887, and “must have been appreciated since a $13.00 honorarium was paid to the speaker who to this day has remained anonymous.” Lowden did find names of several ministers who delivered memorial addresses in the next decade.

Gustavus B. (G.B.) Chadwick

One of Windsor’s Memorial Day speakers, according to Linwood Lowden’s history, was G. B. Chadwick, in 1892. Though not listed as a minister, he almost certainly was: Rev. Gustavus B. Chadwick, a member of a prominent South China family. In the China bicentennial history (where he is consistently referred to simply as G. B. Chadwick), he is mentioned as a school committee member, head of the Masonic Lodge, in South China, and in 1872 among the people who bought the Chadwick Cemetery, where he is buried.

Information from the on-line Find a Grave site says Chadwick was born July 24, 1832, in China. On Aug. 27, 1864, he enlisted in the navy and served as a Landsman on the USS Rhode Island until honorably discharged June 3, 1865. He was a member of China’s Amos J. Billings GAR Post.

Gravestones in China’s Chadwick Hill cemetery list Rev. G. B. Chadwick (did he so dislike the name Gustavus?) and dates; his wife Clara M. (1851-1934) (probably born Clara Erskine); their son Wallace W. Chadwick (1892-1930) and Wallace’s wife Martha Francis (Gardner) Chadwick (1891-1947).

Main sources

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.