Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Wars – Part 4

by Mary Grow

Revolutionary War veterans from Albion, China, Clinton, Fairfield

Note One: this article and next week’s will be about a few of the Revolutionary War veterans who lived in the central Kennebec Valley. Selection is based on two criteria: how much information your writer could find easily, and how interesting she thought the information would be to readers. There is no intent to disparage veterans who are omitted.

Note Two: Alert readers will have noticed in last week’s piece that artist Gilbert Stuart was misnamed Stuart Gilbert. Your writer accepts blame for carelessness; she also assigns blame to Mr. and Mrs. Stuart, for giving their son two last names, or two first names, depending on your perspective.

* * * * * *

Ruby Crosby Wiggin wrote that town and state records and cemetery headstones identify more than a dozen Albion residents who were Revolutionary War veterans. Two, Francis Lovejoy and John Leonard, were among early settlers.

Rev. Francis Lovejoy, grandfather of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, was in Albion by 1790. Wiggin found that he served initially in “Colonel Baldwin’s regiment” and later re-enlisted to fill the quota from his then home town, Amherst, Massachusetts.

(Colonel Baldwin was probably Loammi Baldwin [Jan. 10, 1744 – Oct. 20, 1807], who fought at Lexington and Concord in the Woburn [Massachusetts] militia. He later enlisted in the 26th Continental Regiment, quickly became its colonel and commanded it around Boston and New York City until health issues forced him to resign in 1777. Wikipedia identifies him as the “Father of American Civil Engineering” and the man for whom the Baldwin apple is named.)

Wiggin gave no information on John Leonard’s military service. By Oct. 30, 1802, he owned the house in which Albion (then Freetown) voters held their first town meeting. Wiggin wrote that he held several town offices between then and 1811, when his name disappeared from town records.

* * * * * *

A veteran who settled in what is now China, and whose story has been increasingly revealed in recent years, was Abraham Talbot (May 27, 1756 – June 11, 1840). In various on-line sources, his first name is also spelled Abram, and his last name Talbart, Tallbet, Tarbett, Tolbot and other variations.

Talbot was a free black man. He was an ancestor of Gerald Talbot, the first black man elected to the Maine legislature. Gerald Talbot’s daughter, Rachel Talbot Ross, is assistant majority leader in the current Maine House of Representatives.

Born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, to Toby (or Tobey) Talbot, also a Revolutionary War veteran, Abraham Talbot enlisted in the Massachusetts Line in July 1778 and served his nine months’ term at Fishkill and West Point, New York, until March 1779. He married Mary Dunbar in his home town on Sept. 3, 1787.

When he applied for his pension in 1818, he owned an acre of land in China with a small house on it. He and Mary were the only ones living there, although they had had eight children, born between December 21, 1787, and Feb. 16, 1805, in Freetown (now Albion).

William Farris (1755 – Oct. 19, 1841) was another veteran who in 1832 applied for his pension from China, having previously lived in Vassalboro from either 1796 or 1802 (sources differ). He was a native of Yarmouth, Massachusetts, and on Oct. 5 1775, married Elizabeth Burgess of that town.

An on-line history says he enlisted three times in three regiments: Nov. 1, 1775, for two months in Colonel Putnam’s regiment; February 1775 (a misprint for 1776, as the writer says he enlisted “again”) for two months in Colonel Carey’s regiment; and April or May 1776 for four months in Colonel Berckiah Bassett’s regiment.

His first terms were spent building fortifications in Cambridge and Dorchester, outside Boston. His third enlistment ended in the fall of 1776 on Martha’s Vineyard, “guarding the shore.”

(Colonel Putnam was probably Rufus Putnam [later a Brigadier General], a French and Indian War veteran who was instrumental in building the fortifications that forced British troops to evacuate Boston in mid-March 1776. Colonel Carey was probably Colonel Simeon Cary, commander of “the Plymouth and Barnstable County regiment of the Massachusetts militia,” which was at the siege of Boston. This writer failed to find Colonel Bassett on line.)

William and Elizabeth Farris had “at least eight children.” After she died around 1805, on March 18, 1806, he married a 22-year-old Vassalboro woman, Martha “Patty” Long. He bought a piece of land in Vassalboro in 1816, but was a China resident by 1832. His annual pension amounted to $33.33.

The China bicentennial history lists seven other early residents who were Revolutionary War veterans, including Joseph Evans. Evans, for whom Evans Pond is named, arrived in 1773 or 1774 and left his wife and children in the wilderness when he enlisted.

* * * * * *

Michael McNally (about 1752 – 1848), sometimes spelled McNully, was a veteran who ended his life in Clinton. He served in the Pennsylvania Line up to 1781. An 1896 on-line source says his descendants claimed that his role was driving the horses that pulled cannons.

Family stories reproduced on line give two accounts of his arrival in Pennsylvania: one says he was born as his family emigrated from Ireland, the other that as a youngster he ran away from home and crossed the Atlantic alone. He settled in Clinton around 1785 and “raised a large family.”

* * * * * *

The Fairfield Historical Society writers who produced the town’s bicentennial history in 1988 listed four early settlers who served in the Revolutionary army and 10 veterans who moved in after the war (eight from Massachusetts, one from New Hampshire and one from Georgetown, Maine).

The most prominent was William Kendall (1759 – 1827), referred to in one section as General William Kendall. The history says he enlisted from Winslow in March 1777 and obtained an honorable discharge in 1780. An on-line source says he was a drummer “in various New England regiments.”

Having bought most of the area that is now downtown Fairfield, including an unfinished dam and mill building, Kendall completed that project and added saw and grist mills in 1781. The village center was called Kendall’s Mills until 1872.

On Christmas Day 1782, Kendall paddled up the Kennebec to Noble’s Ferry (Hinckley) in his birchbark canoe and came back with his new wife, Abigail Chase. The couple lived first in a log house by the river at the foot of present Western Avenue, then in Fairfield’s first frame house and later in a large brick house at the corner of Newhall Street and Lawrence Avenue. The last housed Bunker’s Seminary (briefly mentioned in the Oct. 21, 2021, issue of The Town Line); it was torn down in the 1890s.

The Fairfield history says Kendall served eight years as a selectman. An on-line source adds that he was Kendall’s Mills postmaster in 1816, Somerset County Sheriff and a member of the first Maine Senate. He and Abigail had eight sons and three daughters. Kendall is buried in Fairfield’s Emery Hill Cemetery.

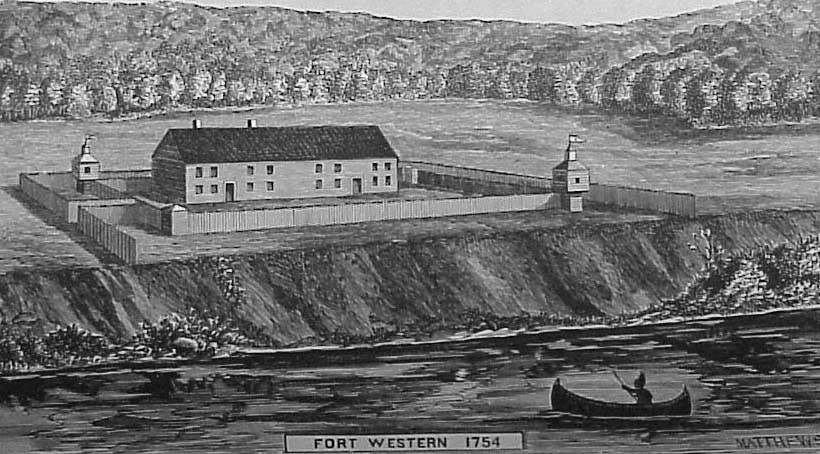

The cemetery, on the river side of Route 201 at the foot of Emery Hill, is near the site of the log house built by Jonathan Emery in 1771 that is called the first house built in Fairfield. Jonathan’s son David (born in Massachusetts Sept. 24, 1754) was one of the four Revolutionary soldiers who enlisted from Fairfield. The historians doubt the story that he enlisted in September 1775, inspired by Colonel Benedict Arnold’s troops marching up the Kennebec on the way to Québec, because dates don’t match.

They did find records showing that David Emery joined the Second Lincoln County Regiment on Mach 12, 1777. On Feb. 2, 1778, he transferred to the Continental Army, where he became part of General George Washington’s personal guard. After being mustered out Jan. 23, 1779, he came back to Fairfield and on April 5, 1782, married Abigail Goodwin. He died in Fairfield; one on-line source gives his date of death as Nov. 18, 1830, another as Nov. 18, 1834.

The other three early settlers who fought in the war were Josiah Burgess (1736 – 1828), a lieutenant from March 1776 to March 1779 in the First Barnstable Company from his home town of Sandwich, Massachusetts; his younger brother Thomas (1741 – 1820), who served in Josiah’s company for a week; and Daniel Wyman (1752 – 1829), who moved up the river from Dresden to Fairfield in 1774 and served three years in the Second Massachusetts Line. After independence, each Burgess brother served as a Fairfield selectman and Thomas was town treasurer for two years.

Jonathan Nye (November 1757 – September 1854) was born in Sandwich, Massachusetts, and is identified on line as serving as a private in 1775 and 1776 at Elizabeth Islands, first in Captain John Grannis’s company and later in Captain Elisha Nye’s company.

(The Elizabeth Islands are an island chain south of Cape Cod and west of Martha’s Vineyard; they compose the town of Gosnold, Massachusetts, named after the British explorer Bartholomew Gosnold, the first European to visit them, in 1602.

(John Grannis was a captain of marines, identified in several on-line sources as spokesman for America’s first whistle-blowers. In February 1777, nine shipmates aboard the frigate “Warren” chose him to jump ship and carry to the government in Philadelphia their charge that Esek Hopkins, in charge of the Continental Navy, was “unfit to lead.” The Continental Congress fired Hopkins.)

The Fairfield history says after Nye’s first one-year enlistment, he enlisted again from Sandwich in the spring of 1777. He was at Saratoga when Burgoyne surrendered and at Valley Forge during the winter of 1778. At some point he became a sergeant. He was honorably discharged at West Point March 7, 1780. After that, the history says, he enlisted yet again for short terms and served on privateers.

The on-line source names his first wife as Mercy Ellis from Sandwich. The bicentennial history calls her Mary Ellis, and says Nye married her “soon after his discharge [in the early1780s, then] and settled in Fairfield.” The history also says that in the spring of 1835, when Nye applied for one of the land grants Congress had just authorized, he said he had lived in Fairfield for 35 years, indicating he moved there in 1800. And in an account of the Nye family in another section of the book, Jonathan Nye is said to have moved from Sandwich to Fairfield in 1788, with his cousins Bartlett (August 1759 – 1822), Bryant and Elisha (Nov. 2, 1757 – 1845) Nye.

On March 18, 1820, Jonathan Nye married again, to Abigail Fish, who died in 1850. When he applied for a military pension in 1820, he said she was not strong enough to help with their farm, and he could not do much because of “blindness caused by small pox while in the army and a lameness in both knees.”

Jonathan Nye’s cousins Bartlett and Elisha were also Revolutionary veterans. Bartlett Nye, according to an on-line family history, served from July 2 to Dec. 12, 1777, in Rhode Island and Massachusetts and again for four days, Sept. 11 through Sept. 14, 1779, as a corporal in Colonel Freeman’s regiment responding to “an alarm at Falmouth [Massachusetts].”

(Colonel Freeman was probably Nathaniel Freeman (March 28, 1741 – Sept. 20, 1827) from Sandwich. He had a medical practice, became active in the Revolutionary movement as early as 1773, was a militia colonel from 1775 and a militia brigadier general from 1781 to 1791.)

Elisha Nye was also in Colonel Freeman’s regiment. He is listed on line as serving for several very brief periods in 1778 and 1779.

After the war, each of the brothers held political office. In 1812, Bartlett Nye was in the Massachusetts General Court, where he supported making Maine a separate state; his term had ended before the decision was taken in June 1819. Elisha, the Fairfield history says, “served as Representative from the County” in 1816, presumably also to the Massachusetts General Court.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.