Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Music in the central Kennebec Valley

by Mary Grow

After the frustration of finding only scanty and random information from local historians on how central Kennebec Valley residents cared for their destitute neighbors, your writer decided to continue frustrating herself on a more cheerful topic: music.

There were music and musicians in central Maine before the Europeans’ arrival. Music historian George Thornton Edwards provided a bit of information on native American music in his Music and Musicians of Maine.

The early European settlers, too, enjoyed and appreciated music, Edwards wrote. At first it was mostly sacred and mostly vocal.

The usual accompaniment to a church choir was a bass viol. Portland’s Second Parish Church seems to have been a leader in expanding use of instruments. Edwards wrote that the cornet and clarinet (or clarionet) had supplemented the viol before 1798, when the church acquired the first church organ in the city.

Augusta wasn’t far behind. In 1802, according to Edwards and to James North’s Augusta history, residents of the North Parish raised $35 to buy a bass viol and build a box for it. Stephen Jewett played the viol; Edwards commented that “ultra conservative” residents no doubt disapproved.

North included a reference from 1796, when Hallowell Academy, opened May 5, 1795, celebrated the end of its first year with public student recitations. North quoted from the May 10, 1796, issue of the Tocsin (Hallowell’s second newspaper): the public presentation included “vocal and instrumental music, under the direction of Mr. Belcher the ‘Handel‘ of Maine.”

(“Mr. Belcher” was Supply Belcher [March 29, 1751 – June 9, 1836]. Born in Massachusetts, he fought in the Revolution; moved to Hallowell in 1785; and in 1791 settled in Farmington for the rest of his life. He published in 1794 a collection of his sacred compositions called The Harmony of Maine.)

North borrowed from Edwards’ history a description of another series of musical events that started in early 1822, when a group of musically-inclined South Parish Congregational Church parishioners brought to the town “Mr. Holland,” a professor of music from New Bedford, Massachusetts. (Your writer has failed to find Mr. Holland’s first name or dates.)

Holland began a new method of teaching “psalmody” (the singing of sacred music, especially in church services) and gave piano lessons. His singers joined the church choir, and the ensuing interest led to raising money to buy a $550 British-made organ, the first organ in Augusta. It was installed on Sept. 4, North said.

The next Sunday, “Mrs. Ostinelli,” Sophia Henrietta Emma Hewitt Ostinelli (May 23, 1799 – Aug. 31, 1845), played the organ. She was the daughter of Boston composer, conductor and music publisher James Hewitt, and the new wife of Italian-born violinist and conductor Paul Louis Antonio Ostinelli (1795 – 184?). An on-line source calls her “pianist, organist, singer, and music teacher.”

Edwards wrote that her husband was described as a violinist “without a peer in America at that time.” He was also an orchestra conductor.

On Sept. 19 and again on Sept. 25, Holland directed “an oratorio of sacred music,” held, Linda Davenport wrote in her Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier, at the church. The concerts were benefits, the first for Holland and the second for the Ostinellis.

Music was provided by church members – the church did not seem to have its own “ongoing musical society,” Davenport wrote – plus choir members from Hallowell’s Congregational and Baptist societies. At one of these concerts, maybe both, Ostinelli played violin solos.

Davenport reprinted the program of the Sept. 19 concert. Each of the two parts began with an organ voluntary, followed by vocal music, both chorus and solo. Seven of the 15 pieces performed were by George Frideric Handel; one was by Franz Joseph Haydn.

North wrote the Holland concerts were the last time such “first class concerts” were presented in Augusta until June 1859, when Ostinelli’s daughter Elise, Madame Biscaccianti, sang.

Holland moved back to New Bedford in September 1823, Edwards wrote. “It is said that his influence on the musical life in Augusta is felt to this day (1928).”

The same year Cyril Searle was “temporarily located in Augusta and he continued the excellent work which had been started by Mr. Holland.”

North devoted three pages to Searle – not to his musical career, but to a description of the sketch he did of Augusta, probably in 1823 (definitely after Maine and Massachusetts separated in 1820, and before a building he included burned on Nov. 8, 1823).

When Augusta’s first Unitarian church, called Bethlehem Church, was built in 1827, it had an organ, North wrote. This church, according to Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, was on the east bank of the Kennebec, where the Cony Flatiron Building (formerly Cony High School) stands today. Since most of the Augusta Unitarians lived on the west side of the river, a new church was built only six years later on State Street, about a block north of the present Lithgow Library.

In later descriptions of new church buildings, North occasionally mentioned an organ; apparently by the 1830s, they were common enough not to be worth noting.

An event he described that will remind readers of the old saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” and in which music played a minor role, occurred in 1832.

By then Maine’s capital had moved to Augusta. The legislature, meeting in secret session, discussed a controversial proposal to cede land to Great Britain to resolve the conflict over the Maine-Canada boundary (a conflict that led to the Aroostook War of 1839 – see the March 17, 2022, issue of The Town Line).

An anonymous source sent information on the secret deliberations to Luther Severance, publisher of an Augusta newspaper, who printed it. Legislators demanded to know the source. Severance refused to answer committee questions and was threatened with a contempt citation, but was apparently never prosecuted.

Enough of Augusta’s elite sympathized with Severance to organize a dinner in his honor, at which speakers denounced legislators, praised the free press and, North quoted from Severance’s newspaper, enjoyed “an excellent dinner, moistened with the best old Madeira, and accompanied by fine music.”

* * * * * *

There were also privately run singing schools, Edwards wrote. Millard Howard wrote in his Palermo history that schoolhouses were one place singing schools met. He added that by the late 1800s, schoolhouses were also sites for “some rowdy dances with frequent fights.”

Edwards’ history includes names of people, mostly men but some women, who ran singing schools. One was Coker Marble, whose singing school in Vassalboro operated for more than 20 years in the period from 1836 through 1856.

An on-line Marble genealogy provides limited information on not one but two men named Coker Marble. The genealogy starts with Samuel Marble (Oct. 23, 1728 -?) and Sarah Coker (June 21, 1735 -?), who married in 1754 in New Hampshire. They had at least three children: Hannah and John, both born in 1755, and Coker Marble Sr. (Sept. 28, 1765 – Aug. 30, 1823).

Coker Marble Sr., married twice, according to the on-line genealogy. He and his first wife, Polly Mason, whom he married about 1796, had at least one daughter.

On Jan. 1, 1801, in New Hampshire, he married Rhoda Judkins (1776 -1864). The oldest of their six children was Coker Marble Jr. (Feb. 8, 1802 – Sept. 10, 1882), who was born in Vassalboro.

In his chapter on Vassalboro in the Kennebec County history, Kingsbury named Rev. Coker Marble as pastor – presumably the first pastor – of the Second Baptist Church, organized at Cross Hill in 1808 with 37 members but, Kingsbury said, “probably…no church property.” From the dates in the genealogical information, this pastor must have been the senior Coker Marble, who would have been in his mid-40s in 1808.

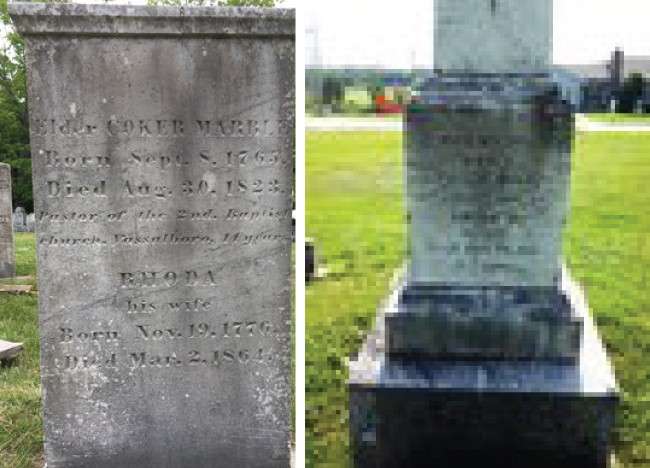

Grave marker for Elder Coker Marble Sr., left, and his wife, Rhoda, on right., at the Cross Hill Cemetery, in Vassalboro.

Vassalboro cemetery records show that Coker Marble Sr., named as Elder Coker Marble, and Rhoda are buried in Vassalboro’s Cross Hill cemetery, with the two youngest of their four daughters.

(Your writer also found on line a biography of a Massachusetts doctor named John Oliver Marble. The biography specifies that he was the son of John and Emeline [Prescott] Marble and the grandson of Rev. Coker Marble. Dr. Marble was born April 26, 1839, in Vassalboro. He graduated from Colby in 1863 and received his medical degree from Georgetown in 1868.)

Coker Marble Jr., married Marcia Lewis (March 19, 1806 – Dec. 17, 1881) on Aug. 31 or Oct. 20, 1824, in Whitefield. Between 1825 and 1853 Marcia bore seven daughters and three sons. The sons were named Arthur, Edwin and Henry.

From the birth and death dates, your writer concludes that it was Coker Marble Jr., who ran the Vassalboro singing school, probably beginning when he was in his early 30s. The genealogy lists two of his and Marcia’s children as born in Vassalboro, in 1837 and 1841, and two others in Hallowell, in 1839 and 1845.

The on-line site says the younger Coker Marble lived in Pittston in 1870 and Skowhegan in 1880; Marcia is listed in Pittston in 1870 and in Milburn in 1880 (Milburn might then have been part of Skowhegan). Both died in Bath (another site says Coker Marble died in either Bath or China) and are buried in Bath’s Maple Grove Cemetery.

Main sources

Davenport, Linda, Divine Song on the Northeast Frontier Maine’s Sacred Tunebooks, 1800-1830 (1996).

Edwards, George Thornton, Music and musicians of Maine: being a history of the progress of music in the territory which has come to be known as the State of Maine, from 1604 to 1928 (1970 reprint).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W. , The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Gaslight Theater’s 2023 Season of Laughter continued in April and May with Peter Shaffer’s Black Comedy, directed by Lucille Rioux. The show will be produced at Hallowell Cithy Hall Auditorium, at 1 Winthrop St., in Hallowell, over two weekends, including Sunday matinees, April 28, 29 and 30, and May 5, 6, 7. Friday and Saturday shows start at 7:30 p.m., and Sunday matinees start at 2 p.m.

Gaslight Theater’s 2023 Season of Laughter continued in April and May with Peter Shaffer’s Black Comedy, directed by Lucille Rioux. The show will be produced at Hallowell Cithy Hall Auditorium, at 1 Winthrop St., in Hallowell, over two weekends, including Sunday matinees, April 28, 29 and 30, and May 5, 6, 7. Friday and Saturday shows start at 7:30 p.m., and Sunday matinees start at 2 p.m.