Coburn Classical Institute

The school that in 1883 became Coburn Classical Institute started in 1821 as the first of what later became four (according to Ernest Cummings Marriner) or five (according to an anonymous website author) college preparatory schools (also called grammar schools, academies, or institutes) associated with what is now Colby College (see box number 1).

Marriner wrote in his history of Colby College that for many years four schools served as feeders for the college: Coburn in Waterville, Hebron in Hebron (founded in 1804 and today a private school for grades six through 12), Charleston, later Higgins, in Charleston (apparently still in operation as a Christian school) and Houlton, later Ricker, in Houlton (founded in 1848, closed).

Colby’s first President, Jeremiah Chaplin (see box number 2), found a shortage of students prepared for college-level work. He therefore got approval from trustees to establish a “grammar school,” at no cost to the college itself.

Classes started in 1821, in the President’s House (also called Wood House, in the triangle where current College Avenue and Upper Main Street meet), at that time the college’s only building. The first teacher/principal was a sophomore named Henry Paine.

When the first campus building opened farther north in 1822, Waterville Classical Institute, also called the College Grammar School or the Latin School, was given space. Albion native and later anti-slavery martyr Elijah Parish Lovejoy (see The Town Line, Aug. 13, 2020), then a student at the college, was teacher/principal from 1824 to 1826.

The new school provided enough qualified college students to impress the trustees. On August 27, 1828, they voted to spend not more than $300 for a separate academy building.

Marriner wrote that Timothy Boutelle, treasurer of the college, had donated land for the Waterville Baptist Church, still standing at the intersection of Elm and Park streets (see The Town Line, June 24, 2021). On the south side of Park Street, where Monument Park has been succeeded by Veteran’s [sic] Memorial Park, was a cemetery. South of that was another lot Boutelle owned (now the site of Elm Towers).

Boutelle donated his south lot for the new building. College President Chaplin raised money to supplement the $300, and Marriner wrote that the final cost, $1,750, had been paid in full when the building opened in the fall of 1829.

During Coburn Classical Institute’s 75th anniversary celebration (June 19-25, 1904), historian and graduate (class of 1875) Edwin C. Whittemore quoted an editorial from the Nov. 4, 1829, Waterville Watchman describing the 42-by-34-foot (plus porch) two-story brick building with a cupola as “a beautiful ornament of our village, not surpassed, we believe, by any other Academy building on the Kennebec.” The editorial also commended the availability of local higher education for families who could not afford, or did not want, to send children away for schooling beyond the elementary level.

The school became Waterville Academy. Mariner wrote that it remained “an adjunct to the College,” dependent on college faculty and on college financing to supplement “very low tuition fees.” The Watchman said tuition was $2.50 for each of the four terms in a year. By 1831 it had risen to $3 a term, and French classes were being added, Whittemore wrote.

Waterville Academy admitted girls from the beginning. Then-Principal Franklin Johnson wrote in his chapter in Whittemore’s 1902 Waterville history that the first class had 63 students, 47 male and 16 female. The 1830 catalog listed two teachers and 61 students, 25 of them girls. One of the girls was Jeremiah Chaplin’s daughter Marcia.

In 1831 college trustees hired a new head man for the academy, the same Henry Paine who had been its first head. In the interim, Marriner said, he had earned a good reputation as head of Monmouth Academy for four years.

Marriner wrote that after Paine left in 1835, Waterville Academy was unable to keep a permanent principal, and, Whittemore wrote, most of those who tried the job were young and inexperienced. College officials lost interest in the academy.

The Waterville Universalists opened the Waterville Liberal Institute, which Whittemore said attracted “many” would-be Waterville Academy students. He wrote that the academy was “wholly suspended” for most of 1839 and 1840. By the winter of 1840-41, Waterville Academy had so few students it closed and let a district school use its building.

Waterville residents were not pleased to lose the school, and an “aroused citizens’ committee” (Marriner’s description) reacted by asking the college to hand over the academy. On Feb. 12, 1842, the state legislature rechartered Waterville Academy with a new town-based board. The new board ran the school, but the college kept title to the real estate, Marriner wrote.

After Nathaniel Butler’s one year in charge, in September, 1843, James Hobbs Hanson, of China, Waterville College ’42, became Waterville Academy principal (see box number three). Marriner wrote that the trustees promised they would have the building repaired, but they offered no salary and guaranteed no students.

Hanson started with six students, increased enrollment to 28 by December and spent $40 more than he took in during his first term, Marriner wrote. Over the next 11 years, enrollment rose to a high of 308 in 1852; but income never sufficed to pay staff and maintain the building.

Whittemore said the first preceptress, Roxana Hanscom, of Waterville, was hired in 1844 and the second story of the building became the girls’ classroom.

Constantly struggling to keep the school solvent, “Hanson broke under the strain and resigned in 1854,” Marriner wrote.

The next 11 years saw Waterville Academy decline steadily, partly because of the Civil War, which, Marriner wrote, was the death of many other Maine private high schools.

In August 1864, the Academy Board of Trustees had many vacancies, and Colby President James T. Champlin suggested the remaining members return the lower school to the college. The college trustees agreed to re-assume control of the preparatory school, which in 1865 they renamed Waterville Classical Institute, and handed the responsibility to the faculty.

According to Whittemore, Champlin further persuaded James Hanson to return as principal, a post he held until he died April 21, 1894.

In 1874, former Maine Governor Abner Coburn (1803-1885) offered $50,000 to Waterville Classical Institute as part of a plan that saw Colby establish official ties with Houlton and Hebron academies (Charleston was added in 1891). He required the school to match his gift, and directed that $40,000 become a permanent endowment fund, with only the interest to be spent.

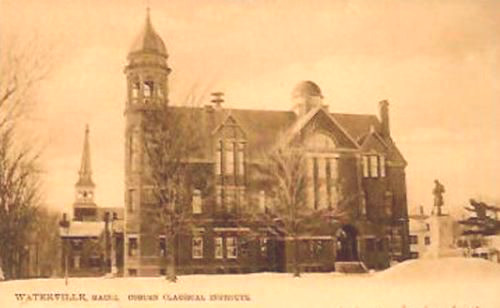

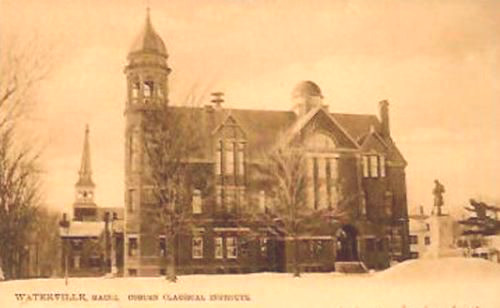

In 1883, Coburn gave the Institute a new building to replace the one built in 1829, as a memorial to his younger brother Stephen and his brother’s son Charles, Colby ’81, who had died July 4, 1882.

On July 3, 1883, Colby trustees voted to change the Institute’s name to Coburn Classical Institute, to recognize Coburn’s generosity. The formal dedication was part of the 1884 college commencement.

In all, Marriner wrote, Coburn donated or willed more than $200,000 to the school.

The family generosity did not end there. During the 1904 75th anniversary celebration, Principal Franklin W. Johnson’s summary of the events included the announcement of a $25,000 matching grant from the family of Stephen Coburn, to strengthen the school’s endowment.

The 1904 principal further commented the Institute had until recently been in sound financial shape. But he, said, in recent years a combination of increasing expenses – he mentioned more and better-paid teachers and more equipment, especially for science classes – and decreasing income due to low interest rates placed Coburn and similar schools “in a precarious position.”

The Coburn family’s gift was therefore vital, Johnson said. Others had been generous during the anniversary, and he and a colleague were in charge of matching the gift within a year.

Back to 1882: The new building on Elm Street was brick. Marriner referred to “spacious rooms, “high ceilings” and an “impressive tower.” It cost more than $50,000, Whittemore said; he added that it took over the site of the 1829 building, which was moved to the back of the lot and later taken down.

An undated on-line photograph shows a three-story building on a basement. Its entrance is from Elm Street, beside a protrusion with two-story columns under a peaked roof at right angles to the main roof.

Two smaller extensions break the front façade on either side of the larger one.

On the south end of the building is a four-story tower with windows in the basement as well as the three stories. A round cupola has either six or eight large arched windows under a round dome.

The smaller central dome on the main roof suggests the photograph was taken after 1893, because, Whittemore wrote, a dome was added that year, after Massachusetts resident Mary D. Lyford and her son donated “a six-inch equatorial telescope” in memory of husband and father Moses Lyford, who taught astronomy at Colby for 30 years.

By the early 20th century, the campus included Libbey field. The City of Waterville owns a poster advertising a Saturday, May 7, baseball game between Coburn and Hebron Academy. Admission was 50 cents.

(This poster creates a minor puzzle. The Waterville website listing this and other historic posters says they date from 1924, 1925 and 1926; but May 7 did not fall on Saturday in any of those years. It did in 1927.)

(Athletics were not new at the institute, though this writer has found few records of organized sports. In a paper prepared for the 1904 anniversary celebration, 86-year-old William Mathews, Class of 1831, remembered snow forts and snowball fights, swimming in the Kennebec River and Messalonskee Stream and running games [a reference to goals suggests football or soccer] on the grounds and, more dangerously, over and around the headstones in the adjacent cemetery.)

In 1901, Whittemore wrote, the Maine Legislature approved separating Coburn from Colby again, organizing the Trustees of Coburn Classical Institute. The main reason for the change was to give the school’s board, instead of the college, control of financial management.

Coburn’s building housed Coburn Classical Institute until it burned on Feb. 22, 1955. After the fire, Marriner wrote, Coburn gave up all but its college preparatory classes and became a private day school. Ancestry.com offers a 1968 yearbook, which it says has 36 pictures of 345 students (an unusually high number for a single year), and lists yearbooks from 1957, 1964 and 1965.

A website says the Institute’s graduates included three United States Senators, eight U. S. Representatives, five governors of Maine, ten justices of the Maine Supreme Court and eight college presidents.

The five governors were Alonzo Garcelon (No. 36); Sebastian Streeter Marble (No. 41); and three other men who served as governor and as a member of Congress: Israel Washburn, Jr. (No. 29), Nelson Dingley (No. 34) and Llewellyn Powers (No. 44).

Whittemore listed four of the college presidents: Colby’s Nathaniel J. Butler, Jr. (1896 to 1901); Colgate University’s George William Smith (1895 to 1897; Colgate is in New York State); Shaw University’s Charles Francis Meserve (1894 to 1919; Shaw is in North Carolina); and Yokohama Theological Seminary’s John Lincoln Dearing (1894 to 1908; Yokohama is in Japan).

In 1970 Coburn Classical Institute merged with the well-housed Oak Grove School, in Vassalboro (see last week’s issue of The Town Line). The combined co-ed school served students from sixth grade through high school until 1989.

The Oak Grove-Coburn student body included day students from Waterville, Vassalboro and other area municipalities and up to 50 boarding students. Boarders came from other parts of the United States and from foreign countries, including Germany, Japan and Spain.

Central Maine newspapers reporter Greg Levinsky quoted former student Jennifer Briggs as appreciating the opportunity to meet people from different places and cultures.

Oak Grove-Coburn was not a religious school, despite its beginnings. Wikipedia says it was noted for “its diversity, community atmosphere and close student-faculty relationships. It was also known for its innovative curriculum.”

The latter included the Wednesday Program, which featured interdisciplinary courses, and Project Week, “offering opportunities for non-academic learning experiences.”

During its 19 years it had four headmasters, whom Wikipedia lists as Andrew C. Holmes (1970-9173), Fred B. Steinberg (1973-1979), Dan Fredricks (1979-1981) and Dale Hanson (1981-1989).

Oak Grove-Coburn’s highest enrollment was 175 students, Levinsky wrote. By the late 1980s enrollment was down to around 100, not enough to pay the bills. Financial failure forced the school to close in 1989.

1 – Colby College

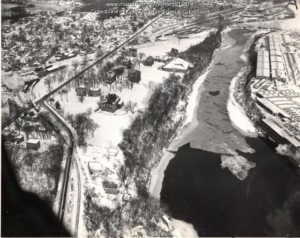

Original Colby Campus on College Ave., in Waterville

The school that is now Colby College on Mayflower Hill (and, returning to its roots more than 300 years ago, in downtown Waterville) received its original charter as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution in the spring of 1813, from the Massachusetts legislature. It is Maine’s second oldest college, after Bowdoin, chartered in June 1794.

Most of Colby’s founders were Maine Baptists. However, from its beginning the Institution was non-denominational in practice, accepting other Christians as faculty and students.

In the spring of 1815, Ernest Cummings Marriner wrote in his history of Colby College, a legislative committee gave the Institution a land grant – Township Three, west of the Penobscot River, north of what is now Old Town. By September, the school’s trustees had visited the area and found it unsuitable for building an educational institution.

They invited towns closer to what were then European-inhabited parts of Maine to offer sites, and in October 1817 chose Waterville. Having decided on the town, they next decided on a site: the west bank of the Kennebec on the road running north from Waterville to Fairfield.

Earl Smith, another historian of the college, said the site was about half a mile north of what was then downtown Waterville. The original 179-acre plot was later reduced as land was sold to raise money.

In those days, Marriner wrote, much of the road to Fairfield ran through woods. He described volunteer residents cutting down trees to make space for the first two college buildings in 1821 and 1822; and quoted from a letter describing the “candles in the students’ rooms…glimmering on the dense forest.”

Meanwhile, the Institution had been re-chartered by the new legislature after Maine became a state on March 15, 1820, and authorized to grant degrees. Legislators also promised $1,000 a year for seven years, on condition that at least a quarter of the grant be used to reduce tuition. On Feb. 25, 1821, Marriner wrote, the Maine legislature renamed the Institution Waterville College.

The first brick building, South College, was finished in the fall of 1821, and the first two students graduated in August 1822.

Marriner listed three significant changes during Jeremiah Chaplin’s presidency, from 1818 to 1833: Waterville College opened a medical school, discontinued the theological branch and started a student aid workshop.

The medical school, in conjunction with a similar Vermont school, was dissolved in 1833; Marriner said no explanation was provided.

The theological department lost students steadily, as Baptists who resented the post-1820 emphasis on a secular curriculum sent their sons to the new Newton (Massachusetts) Theological Institution, founded in November 1825. The last five theological graduates completed their studies in 1825.

The workshop was just that, a place where students earned part of their tuition by building wooden house fittings and furniture to be sold. Started in 1828, it consistently operated at a deficit, and was discontinued in the spring of 1841. Chaplin favored it, and his support might have been one reason it lasted as long as it did.

For most of the 1840s, 1850s and 1860s, while preparatory school and college were separate, the college struggled with low enrollment, unpaid tuition and mounting bills. By 1864, as the Civil War ended, there was talk of closing Waterville College, Smith wrote.

One Sunday that winter, Gardner Colby, a Boston-area man who had made a fortune selling the woolen cloth his company made to the Union Army, heard his preacher recall a meeting 40 years earlier with President Chaplin, who was trying to raise funds for Waterville College.

Colby had lived in Waterville as a youth, in extreme poverty, and Chaplin had helped him and his mother and siblings. When the first college building opened in 1821, Colby was there, and he never forgot the celebratory candles glowing from the windows, lighting up the woods.

At the 1864 college commencement, Colby announced that he would donate $50,000 to the school if the school would match it with $100,000. Smith described the announcement as a total surprise to all but the college president: “The audience sat in stunned silence and then erupted into wild cheering and stomping.”

The matching money was raised, Colby became a college trustee and on Jan. 23, 1867, the state legislature rechartered the school as Colby University.

In 1871, trustees voted to admit women, in an effort to increase enrollment. The school remained coeducational until 1890; by then, Smith wrote, “growing uneasiness over the academic dominance of women students” led the trustees to retreat to what Smith called “a coordinate university.”

When Nathaniel Butler, Jr., came from the University of Chicago to become Colby President in 1896, Smith wrote that, “he knew a university when he saw one. Colby was no university.” Butler promptly started a campaign to change the name, with the result that on Jan. 25, 1899, the Maine legislature renamed the school Colby College.

The move from the closely-hemmed-in College Avenue campus to Mayflower Hill began after Colby graduate Franklin Winslow Johnson became President in 1929. Interrupted by the Depression and World War II, it took more than 20 years to finish.

Smith wrote that teaching continued on the College Avenue campus until May 1951, and the Class of 1956 was the first whose members had spent all four years on the Hill. Robert Frost was their commencement speaker.

2 – Jeremiah Chaplin

Jeremiah Chaplin (Jan. 2, 1776 – May 7, 1841) was born into a Baptist family in Rowley, Massachusetts. He graduated in 1799 from Brown University, which Ernest Cummings Marriner wrote was “the only Baptist college in New England,” studied theology in Boston and in 1802 began preaching and teaching would-be preachers in Danvers, Massachusetts.

Marriner surmised that one reason the trustees of the Maine Literary and Theological Institution invited Chaplin to become its first Professor of Divinity was that he had seven students in Danvers – seven new students for the Waterville school.

Marriner described in detail the June 1818 trip Chaplin, his wife Marcia and their five surviving children, aged from five months to 11 years, made from Boston to Waterville. As far as Augusta the family traveled up the Kennebec on a sloop named “Hero”, whose replica tops the tower of Miller Library on Colby’s Mayflower Hill campus.

The last miles, from Augusta to Waterville by longboat (half an hour by car when Marriner wrote in 1962), took from 2 p.m. one day to 10 a.m. the next. The family spent the night in a farmhouse that Marriner thought was likely at Getchell’s Corner in Vassalboro.

In Waterville, welcoming residents escorted them to college treasurer Timothy Boutelle’s home. Later they moved into the house formerly owned by the late James Wood, rented by the college for the family and the seven students. The house was on the north edge of town, where Elmwood Primary Care now stands, at the junction of College Avenue, Upper Main Street, Elm Street and Main Street.

Chaplin’s early responsibilities included nagging the trustees to raise money for current expenses – including his promised salary of $600 a year; in the first year he was paid $490, and generously offered to forget about $100 of the arrears – and for the planned college buildings. He was also eager to get a literary professor on staff, a position filled in October 1819.

When Waterville College was chartered in February 1821, the trustees realized they needed a college president. After one man turned them down, they elected Chaplin president in May 1822.

They further authorized the new president to take as much time off as he wanted to solicit funds for the college, and appointed one of their own board members to serve as Professor of Theology while Chaplin was away.

In 1829, in a vain effort to resurrect the studentless theology department, the trustees appointed Chaplin Professor of Divinity again. He taught no courses and resigned the title in 1831, remaining college President and Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy.

The events that led Chaplin to sever his Waterville College connection started on July 4, 1833, when a noisy student gathering created the Waterville College Anti-Slavery Society.

Chaplin was not pro-slavery and he was not anti-organization, Marriner wrote; but he objected to “anything which marred the sober decorum that must be observed in any institution of which he was the head,” especially one educating future ministers. On July 5, therefore, he publicly dressed down the students in terms that infuriated them. He also expelled two students and gave half a dozen others long suspensions.

After heated exchanges and a failed attempt by the trustees to reconcile Chaplin with the students and the faculty members who sided with them, the trustees accepted Chaplin’s resignation as professor and president on July 1, 1833. They promptly elected him a member of the board, a position he held until 1840; and Marriner wrote that he remained a Colby supporter the rest of his life.

In addition to organizing the Literary and Theological Institute, Chaplin founded the First Baptist Church of Waterville and led what Marriner said was “a vigorous but unpopular temperance movement” in the town.

After leaving Waterville, Chaplin preached in Massachusetts and Connecticut. He died in Hamilton, New York.

3 – James Hanson & wife

James Hobbs Hanson (June 26, 1816 – April 21, 1894) was a China (Maine) native who came from China Academy to Waterville College, where he graduated in 1842. Kinsgbury wrote that he began teaching in 1835, while still at China Academy, and taught the rest of his life. He took over the management of the Waterville academy in 1843, resigned in 1854, and returned to hold the post from 1865 until he died.

Between 1854 and 1865, an on-line source says he spent three years as Eastport High School principal, six more years as Principal of Portland High School (Boys’ High School, according to Edwin Whittemore) and two years running a private boys’ school in Portland.

Historians of the academy uniformly credit Hanson with all its successes, and do not blame him for its financial difficulties. Whittemore wrote in his chapter in the history of Waterville that Hanson headed the school for 41 of its first 65 years: “in fact, he was the school.”

In addition to teaching – “When other men wrought six hours in the classroom, he wrought twelve,” Whittemore quoted from George B. Gow’s address at the 1879 semi-centennial celebration – Hanson was continuously involved in fund-raising. Whittemore quoted more of Gow’s words:

“Too poor to employ the needed assistance, too conscientious to lave anything undone that might be of use to the most ungrateful pupil, he toiled on seeking no reward but the satisfaction of doing his whole duty.”

In 1854, after the death of his first wife, Hanson married Mary E. Field, from Sidney, who had been preceptress since 1852. When the Hansons returned to Waterville in 1865 she became one of the Institute faculty, reportedly popular and, like her husband, willing to take on whatever job needed to be done.

Hanson somehow found time to write the “Preparatory Latin Prose Book” (1861) that the on-line source says was widely used. He was one of the editors of a “Handbook of Latin Poetry”, published in 1865. Whittemore wrote that his reputation as a classical scholar brought “large numbers” of students from other preparatory schools to spend their senior year at the Waterville institution.

In 1862 Hanson was elected a trustee of Waterville College. In 1872, Colby University gave him an honorary L.L.D. Kingsbury commented that Colby “honored itself” by conferring the award.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Marriner, Ernest Cummings, The History of Colby College (1963).

Smith, Earl H. , Mayflower Hill A History of Colby College (2006).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous