Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Clinton, China Libraries

by Mary Grow

Clinton’s Brown Memorial Library

China’s Albert Church Brown Memorial Library

Brown Memorial Library, in Clinton, is the third of the local libraries on the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1899-1900, it was added to the Register on April 28, 1975.

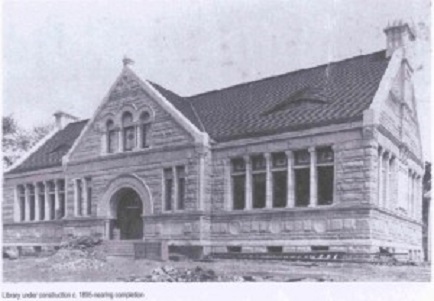

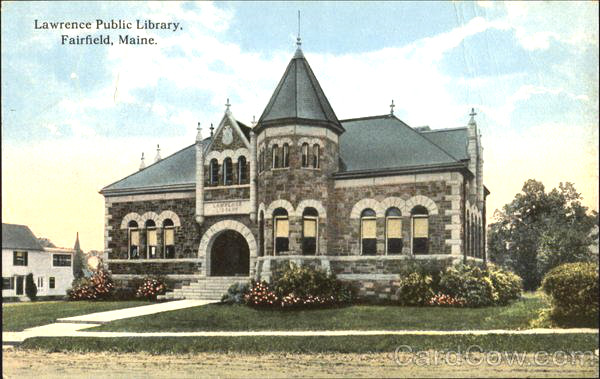

In their application for the listing, Earle Shettleworth, Jr., and Frank A. Beard, of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, compared the Brown Memorial Library to Fairfield’s Lawrence Library (see The Town Line, Nov. 11) and Augusta’s Lithgow Library (see The Town Line, Nov. 18).

Architecturally, all three buildings are variations on the style of Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886). Shettleworth and Beard called Clinton’s library “a purer example of the Richardsonian ideal with an exterior exhibiting warm hues and contrasting colors in stone walls and trim, as opposed to the almost monochromatic use of granite and slate,” in Fairfield and Augusta.

Also, they wrote, “The Clinton Library, though symmetry is implied, is basically an asymmetrical composition, truer to Richardson’s buildings of the same type than either the Lithgow or Lawrence libraries, which reflect contemporary Beaux Arts symmetry clothed in a Richardson-derived exterior.”

They concluded, “The Clinton Library is the most exemplary structure of its kind in Maine and is an unusually large and elegant library for a small, rural community.”

Portland architect John Calvin Stevens (1855-1940) designed Brown Memorial Library. He has been mentioned before as the architect chosen to remodel Augusta’s Blaine House in 1920. Other Maine libraries he designed include Rumford Public Library, built in 1903 and added to the National Register in 1989; and Cary Public Library, in Houlton, opened in 1904 and added to the National Register in 1987.

Clinton’s library is on Railroad Street just north of the Winn Avenue intersection. Shettleworth and Beard described a single-story stone building on a partly raised basement (with windows), with a hipped roof. Reddish sandstone trim contrasts with greyish granite walls and a grey slate roof.

The building’s rectangular shape is broken by three “projections,” small ones on the back and south side and, on the front, to the right (south) of the main entrance, “a large five-bay projection trimmed in sandstone and capped with a semi-detached conical roof.” This projection features tall windows with narrow stone dividers between them.

The entrance is approached by granite steps and recessed under an arch. Above the arch is a “dormer:” a rectangular panel with the words “Brown Memorial Library”; above it, two small rectangular windows; and above them “a steep triangular pediment topped with a ball finial.”

Entry is through two doors with glass panels topped by “a colored glass transom,” Shettleworth and Beard wrote. The “small porch” inside the arch “is floored with a marble mosaic pattern.”

The north side of the front wall has two tall windows, narrower than the ones in the south tower.

The historians noted the origin of the various building materials. The rough granite for the walls is from Conway, New Hampshire; the sandstone for trim is from Longmeadow, Massachusetts; and the slate for the roof “was quarried nearby on the banks of the Sebasticook River.”

An on-line Town of Clinton history adds that the “ledge for the foundation” came from Clinton farmer J. T. Ward’s land.

Inside, the “vestibule,” “entrance hall” and original librarian’s room were straight ahead (by 1975, Shettleworth and Beard wrote, the librarian’s room was a children’s room). The room to the left was the stacks.

The reading room on the right is “the largest room in the building.” Lighted by the bow windows on the front and a smaller one on the side, the room has “a large fireplace flanked with built-in seats” on the back wall (the library’s “Cozy Nook”) and a pine ceiling “patterned with trusses and panels.”

“The interior plan, like the exterior, exhibits Steven’s faithfulness to Richardsonian principals [sic], being designed with a logical, functional simplicity,” Shettleworth and Beard wrote.

Clinton had no public library until William Wentworth Brown (April 19, 1821 – Oct. 22, 1911), born in Clinton but by 1899 living in Portland, bought the land, paid for the building and provided a $5,000 endowment (earning an annual income of $350, according to the 1901 annual report of the state librarian). The town history article says Horace Purinton, of Waterville, was the contractor for the building.

Shettleworth and Beard wrote that Brown presided at the Aug. 29, 1899, ground-breaking. The cornerstone was laid Sept. 25, “amid elaborate ceremonies.” The building opened to the public on July 21, 1900, and was formally dedicated on Aug. 15, when Brown presented it to the residents of Clinton.

The town history article identifies the first librarian as Grace Weymouth, “a descendant of Jonathan Brown [William Brown’s father].” One of William Brown’s four older sisters is listed on line as Eliza Ann Brown Weymouth.

Shettleworth and Beard wrote that Brown also provided many of the “books, furnishings and pictures.” The state librarian wrote that the library started with 2,500 books and had space for 10,000.

In 1902, Shettleworth and Beard said, Orrin Learned added “100 volumes of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies.” Library Assistant Director Cindy Lowell says they are still stored in the building.

(Orrin Learned [June 16, 1822 – July 2, 1903] was a Burnham native who moved to Clinton in 1900. He attended Benton Academy and, like his father Joel, made his living farming and lumbering in Burnham. He served on the select board and school committee and was a state representative in 1863 and 1873 and a state senator in 1877 and 1878.

The on-line biography of Learned says nothing about military service, Civil War or other, except that he was the great-grandson of Revolutionary War General Ebenezer Learned, who was Brigadier-General under Horatio Gates at the October 1877 Battle of Saratoga, where British General John Burgoyne was defeated.)

Clinton officials dedicated the June 2012 town report to the library. They explained that the 1899 trust specified that part of the trust fund interest would be used for “maintaining the building and library,” and that the operating budget would come from local taxes.

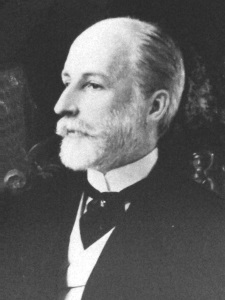

One of Brown’s gifts was Vinton’s portrait of him, Shettleworth and Beard wrote.

(An on-line search found Frederic (or Frederick) Porter Vinton [Jan. 29, 1846 – May 19, 1911], a Bangor native who lived in Chicago and later Boston, where he studied art at the Lowell Institute and in 1878 opened his portrait studio. Vinton began painting landscapes in the 1880s, but is known primarily as a portrait painter.)

Lowell said in late November 2021 that the huge painting had been sent away to be cleaned and restored. The restorers had uncovered a fur collar that had been completely obscured over the years, she said.

Brown said at the library dedication that it was a memorial to “my dear parents who were my ideal of all that is best and purest in life….” He expressed the hope that “the good to be derived from this gift may go on forever.”

* * * * * *

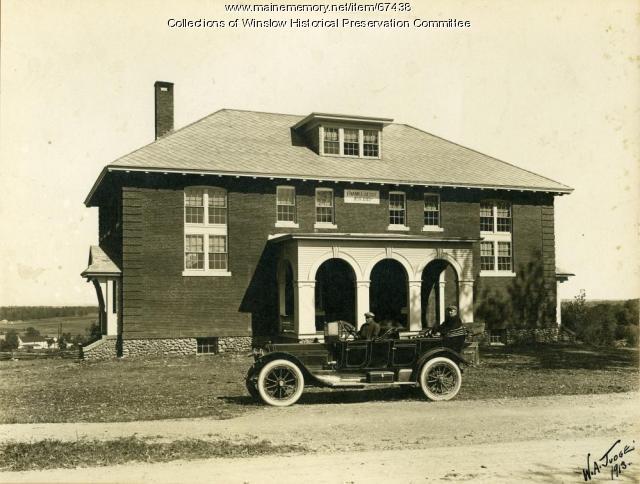

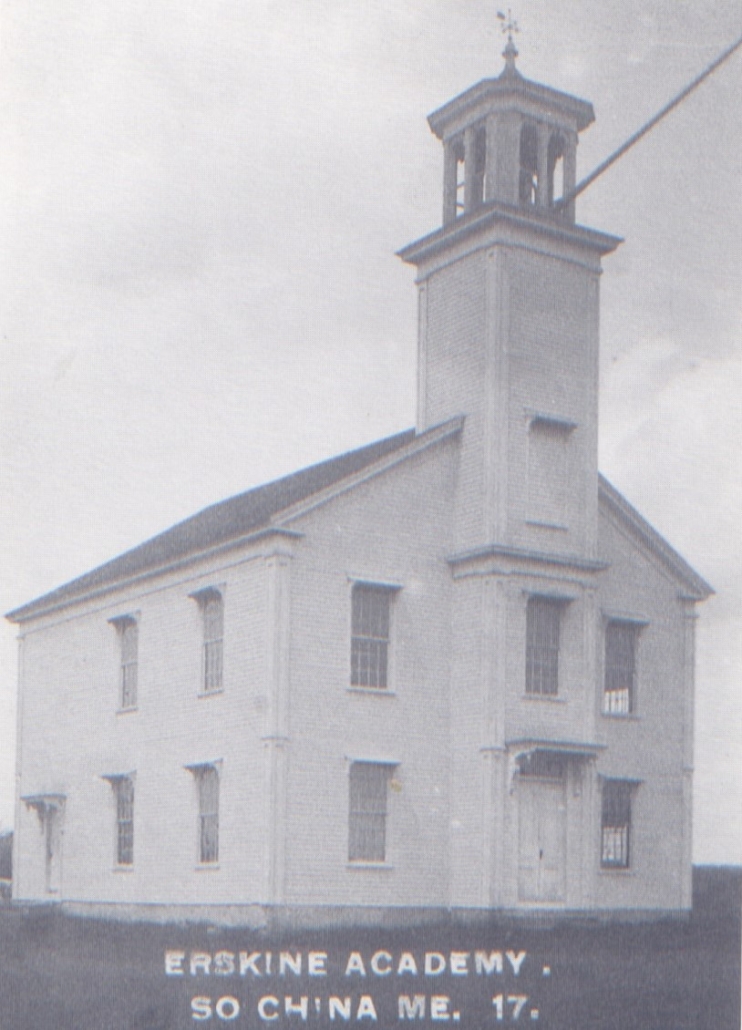

The Albert Church Brown Memorial Library, on Main Street, in China Village, less than 15 road miles south of Brown Memorial Library, in Clinton, has been in existence only since 1936, and in its present building since Jan. 1, 1941. Its name honors Albert Church Brown, whose widow donated money to buy and renovate a house dating from around 1827.

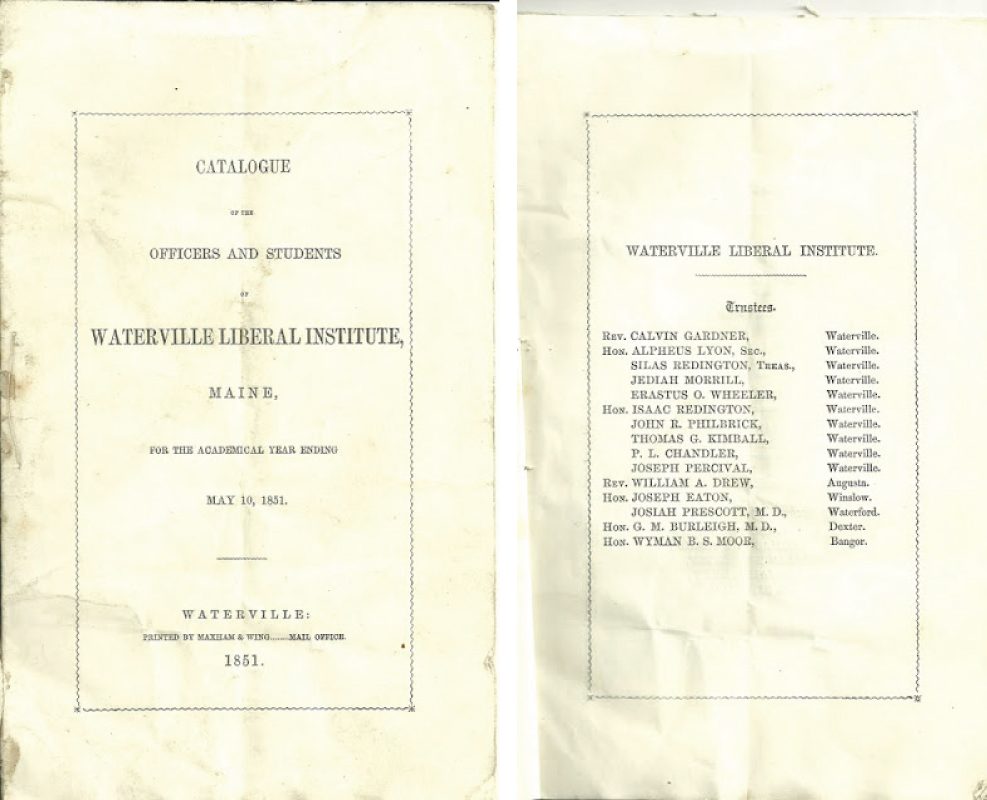

Albert Church Brown (no known relation to the Clinton Browns) was born in Winslow in 1843. He grew up in China; the China bicentennial history says he left when he was 16.

After service in the Civil War, Brown prospered as a businessman in Malden, Massachusetts. He died in 1922, leaving his widow, whose family connections with former China residents led to her interest in the library.

The two-story Federal building was formerly known as the Fletcher-Main House, after the two intermarried families who owned it. The building is in the China Village Historic District, a group of mostly residential buildings added to the National Register of Historic Places on Nov. 23, 1977 (see The Town Line, July 8, 2021).

The two Brown libraries share an interesting reputation: people who worked or work in each repeat the superstition that the buildings are haunted.

In Clinton, Assistant Director Cindy Lowell said the ghost is taken to be William Wentworth Brown himself, or “WW,” as she and colleagues call him. She cited two examples of “WW is up to something again.”

Once, she said, the library director’s eyeglasses vanished. Staff and patrons searched the building in vain. Days later, a fuse blew; Lowell went to the basement to replace it, and the missing eyeglasses were on the basement floor.

Another time, Lowell had just come to work, alone, when she heard a very loud slam in the basement. She waited until a patron came in before she went down to investigate – and found no explanation, nothing out of place.

Your writer is the former librarian at China’s Brown Memorial library. Several people familiar with the building assured her there was a ghost, though no one knew who it was. More than once she heard noises as though someone were moving upstairs when she was sure no living person was there; and if the sounds were made by mice, they left no other sign of their presence.

William Wentworth Brown

Various on-line sources say that William Wentworth Brown was born in Clinton on April 19, 1821, sixth of the seven children of Jonathan Brown (1776 – 1861) and Elizabeth “Betsy (or Betsey)” Michales (or Michaels) Brown (1784-1850). His parents and sister, Eliza Ann, are buried in Clinton’s Riverview Cemetery.

Jonathan and Elizabeth Brown were donors of Clinton’s Brown Memorial Church, now Brown Memorial United Methodist Church, according to Brown Memorial Library Assistant Director Cindy Lowell.

William Brown lived in Clinton until he was 21, when he moved to Bangor to work in his brother’s grocery business (probably his older brother, Warren, born in 1811).

In 1845, Brown started making timbers, decking and other essential pieces of wooden ships. In 1857, he moved the successful business to Portland.

Brown took note of the use of ironclads in the Civil War (the battle between the “Merrimack” and the “Monitor” was on March 9, 1862), and when in 1868 he and Lewis T. Brown (no relation?) were offered a chance to buy a sawmill in Berlin, New Hampshire, he changed businesses.

The two Browns enlarged the sawmill. In the 1880s William Brown bought out Lewis Brown and became sole owner of the Berlin Mills Company, as it was known until it became the Brown Company in 1917. This mill was one of several pulp and paper mills in Berlin.

Lowell quoted a report on the History Channel saying that Brown’s home in Berlin is now a museum.

On Feb. 6, 1861, Brown married his first wife, Emily Hart (Jenkins) Brown (Jan. 23, 1836 – Apr. 4, 1879), from Falmouth, Massachusetts. His second wife was Lucy Elizabeth (Montague) Brown (Jan. 16, 1845 – May 16, 1927); no marriage date is given. Genealogical records contradict each other on how many children he and his successive wives had.

This writer has found no information about William Brown’s career after the 1880s. She assumes it was profitable. Nor has she found any explanation for his decision that a library was the appropriate memorial for his parents.

William Brown died Oct. 27, 1911. He is buried with both wives and five children in a family plot in Portland’s Evergreen Cemetery.

Main sources

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Shettleworth, Earle G., Jr., and Frank A. Beard, National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form, Brown Memorial Library, April 4, 1975.

Personal interview.

Websites, miscellaneous.