Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Wars – Part 6

by Mary Grow

War of 1812

The end of the American Revolution did not end enmity between Britain and its former colonies. They fought one more war, the War of 1812 (June 18, 1812 – Feb. 18, 1815).

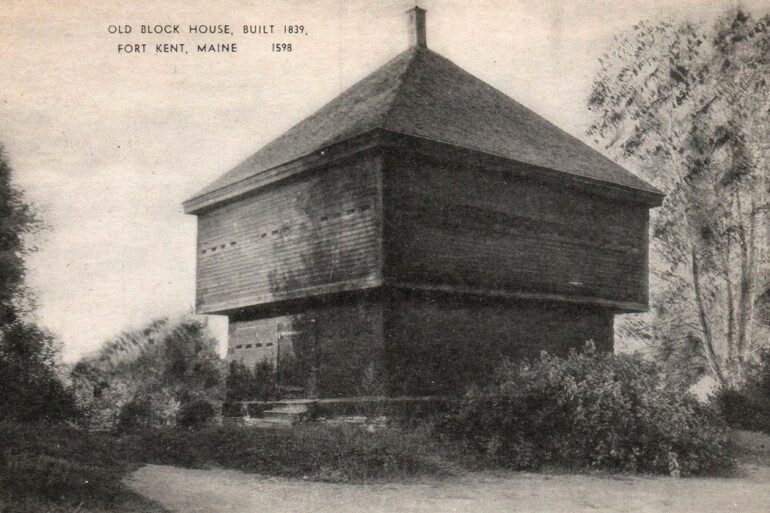

Even after that war, the border between the United States and British Canada remained partly unsettled until the Oregon Treaty of June 15, 1846. In the interim, one eastern border disagreement reached the point where it, too, is called (or miscalled; some historians insist it was a mere incident) a war, the Aroostook War (1839-1840).

The next articles in this series will talk about the War of 1812 and the Aroostook War.

From 1806 on, relations among the United States, Britain and other European belligerents, and within the United States between the pro-British Federalist party and the pro-French Democratic Party, became increasingly unfriendly. The United States banned imports in British ships; the British retaliated by attacks on American shipping.

Louis Hatch’s 1919 Maine history includes an interesting summary of the War of 1812. He discussed both the anti-war sentiment that was significant in all of New England and the ways many Maine people supported the war.

Although anti-war Federalists dominated in Augusta in the years before 1812, they were a minority in Kennebec County, the District of Maine and the United States, James North wrote in his Augusta history. He said Maine reportedly furnished more enlisted soldiers in proportion to population than any other state, and patriotically paid war taxes Congress required.

Casual students of Maine history probably think the war’s effects were limited to coastal and Downeast Maine – the British seized Castine and Machias and went up the Penobscot as far as present-day Bangor.

For some local historians, that view seemed accurate. For example, Vassalboro historian Alma Pierce Robbins gave the War of 1812 one sentence, saying it was unimportant to Vassalboro officials, perhaps because it wasn’t really a war. (Hatch, however, listed Vassalborough and Waterville as towns whose voters rejected proposals to petition the federal government to repeal the embargo on international trade.)

Similarly, in the town of Harlem, now China, the 1974 town history says that “There are no records of war casualties. The Harlem town records show no extraordinary political or financial effects.”

Others, notably Augusta historians North and Charles Elventen Nash, found that the War of 1812 had major and lamentable economic, personal and political effects. Nash and North wrote at length about the war, because both were detail-oriented and, perhaps, because Augusta was then the largest town in the area.

In his 1870 history, North wrote that as early as 1806, the war between Britain and France made Maine settlers fear the United States government would be forced to abandon the policy of neutrality that was commercially beneficial. Anticipating trouble, he said, Kennebec Valley people began thinking in military terms – hence, for example, the 1806 organization of Augusta’s first military company, the Augusta Light Infantry.

North called the Light Infantry Augusta’s “first independent company.” His account of the ladies of Augusta presenting a company standard on Sept. 11, 1806, says the cavalry and artillery units were waiting when the uniformed infantrymen arrived to receive a white silk standard with “Victory or Death” inscribed in red.

In December 1807 Congress passed the Embargo Act prohibiting United States exports to Europe. The act was a disaster for businessmen trading overseas, including many Kennebec Valley merchants and ship-builders; stopping trade stopped their livelihoods.

“[T]heir ships instead of making profitable voyages lay decaying at the wharves, and financial distress and in many cases bankruptcy followed,” Nash wrote.

On Aug. 20, 1808, voters at a special Augusta town meeting petitioned President Thomas Jefferson to repeal the embargo. Debate was spirited, North wrote; when the vote was taken, only seven men dissented.

A nine-man committee drafted a petition that was approved and forwarded to Washington. North quoted President Jefferson’s Sept. 10 reply defending the embargo and reminding Augusta residents that only Congress could repeal it unless the European powers first abandoned their anti-trade edicts and actions.

On Jan. 16, 1809, Augusta voters acted on a broader resolution condemning the embargo, a war with Britain and creation of a standing army. The vote was 85 in favor to 23 opposed, North wrote.

In 1810, North wrote, the Federalists and the Democrats held separate Fourth of July celebrations. The Democrats met in front of a Grove Street house to hear Nathan Weston’s speech; the Federalists, with the Augusta Light Infantry, paraded around the city, including past the Democratic gathering, “courteously suspending their music as they passed.”

(Nathan Weston was then a district judge; he was later an Associate Justice and Chief Justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. See The Town Line, Dec. 10, 2020.)

The Federalists’ parade was followed by a banquet at a Hallowell tavern, in a room decorated with 17 wreaths for the 17 United States. North wrote that Virginia’s wreath included a hornet’s nest, “representing the stinging nature of her democracy.” A candle set the nest on fire and freed the hornets.

President James Madison continued the embargo and on June 18, 1812, signed the Congressionally-approved declaration of war with Great Britain.

The news reached Augusta around the beginning of July. Local Federalist party leaders and press denounced the declaration – North quoted the words “iniquitous, ruinous and not to be tolerated.” President Madison was hanged in effigy, and a fast in protest was held July 23.

Historian Henry Kingsbury added that federal troops stationed in Augusta were ready to counter the local reaction, “and but for the action of the civil authorities the episode must have closed with bloodshed.”

War worsened an already-bad economic situation in the Kennebec Valley. In Augusta, North summarized:

“The streams of prosperity were dried at their source, and in the general depression which followed Augusta had her full measure of distress; her wheels of industry in a measure stopped, her navigation dwindled, and her trade nearly ceased; and for many years her prosperity and growth were greatly retarded.”

Nash agreed, describing a “steady, visible decline” in business from 1807 to 1814.

Both historians saw 1813 as the low point. That year, Nash said, no new ships and very few new houses were built in town.

“Large and numerous piles of manufactured lumber ready for shipment cumbered the banks of the river, and there gradually deteriorated into a condition of little value,” Nash wrote. North added that downtown Augusta was ruined. By 1813, he wrote, “The town presented…a desolate appearance.”

Five major stores in brick buildings had closed, he said; only one store was still in business, Nash added. North wrote that the downtown buildings were owned by out-of-towners, some from the area, one from Massachusetts, one from Maryland.

On June 8, 1813, an Augusta-owned ship with an Augusta cargo was seized by a British ship. Captain and crew were promptly released, but the ship and cargo went to Nova Scotia.

Nash found that in 1808, 1809 and 1810, Augusta businessmen owned more than 1,000 tons of shipping. By 1817, three years after the war ended, the figure was less than 100 tons.

The war caused inflation. North offered sample retail price comparisons between 1811/12 and May 1813, including corn rising from a maximum of $1.28 to $1.70 and flour from $11 to $17 (he gave no measurements; corn per bushel and flour per barrel seem probable).

The beginning of 1814, he wrote, “was gloomy in the extreme; all imported articles continued extravagantly high. Breadstuffs were scarce and difficult to obtain, and a spirit of speculation was rife, induced by exorbitant and fluctuating prices.” There was considerable smuggling; the few remaining Augusta merchants were occasional participants.

Waterville residents, too, reacted to the 1807 embargo, historian Edwin Carey Whittemore wrote. They called a town meeting (no date is given) that was intended to approve a petition to the federal government to rescind the embargo and allow trade; “but the spirit of patriotism prevailed and the town authorized a resolution approving the Embargo” and appointed a committee to write and send it.

Soon afterwards, Whittemore wrote, another meeting authorized a powder magazine in the meeting-house loft, “probably as the driest place available.”

Otherwise, Whittemore ignored the war and skipped to 1814, when, he wrote, one of the Waterville shipyards launched “the largest ship ever built here,” the 290-ton “Francis and Sarah”. After the war, Waterville became a hub of water-borne trade on the Kennebec.

The war ended with the Treaty of Ghent on Dec. 24, 1814. North wrote the news reached Augusta Feb. 11, 1815, where it ignited “the liveliest demonstrations of joy. Bells were rung and bonfires kindled….” There was another celebration Feb. 14, a religious service of thanksgiving Feb. 22 and on April 13 a “national thanksgiving.”

In the next months, he wrote, commerce revived, but taxes to cover war costs continued: “a direct tax on lands and dwelling-houses, and specific taxes on household furniture, watches and stamps, on retailers, manufacturers and carriages.”

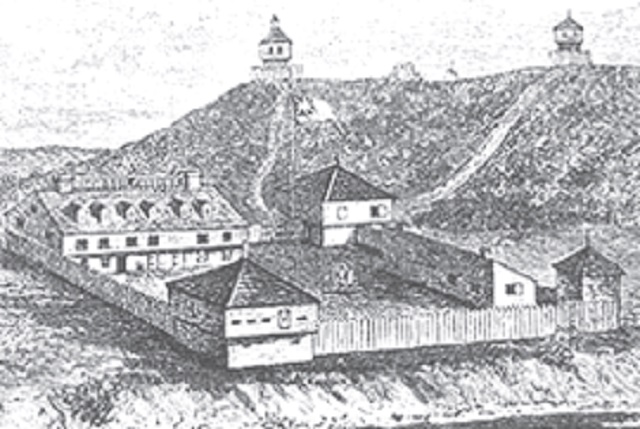

Augusta got a belated bonus from the War of 1812: the federal government built the Kennebec Arsenal between 1828 and 1838, as the disputed Maine-Canada boundary kept relations with Britain uneasy.

A 1997 article by Maine historians Marius B. Peladeau and Roger G. Reed (found on line) explains that the events of 1812-1814 showed how easily a naval power like Britain could disrupt water transport of war supplies to the Maine frontier from the nearest arsenal, in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Therefore, on March 3, 1827 (10 days after Governor Enoch Lincoln approved the state law making Augusta Maine’s capital, Peladeau and Reed commented), President John Quincy Adams signed a law ordering the Secretary of the Army to site and build an arsenal at Augusta.

An Army engineer chose a 40-acre lot on the east bank of the Kennebec. The plan expanded from a “depot” for supplies from Massachusetts to “an arsenal complex large enough to fabricate military supplies and be semi-independent” if communication with Massachusetts were interrupted.

Congress tripled the initial $15,000 appropriation to $45,000, and, Peladeau and Reed wrote, the cornerstone for the first of 15 buildings was laid June 14, 1828. Ten of the buildings were of “unhammered granite, laid in ashlar courses, from the already famous nearby Hallowell quarry.” The rest were wooden.

“As is so often the case when the government is involved,” the authors observed, there were cost overruns. On March 27, 1829, Congress added another $45,000 to the arsenal budget.

Peladeau and Reed described the main building as 100 by 30 feet, three stories high with a “spacious basement.” It had room for 142,760 muskets. Nearby were two powder magazines, officers’ quarters, barracks, a guard house, a stable and “shops for the blacksmiths, armorers and wheelwrights.”

An eight-foot-high iron fence on a granite foundation surrounded the entire lot. There was a granite retaining wall along the river and, not finished until 1833 or later, a granite wharf “at which vessels drawing ten feet of water could dock even when the river experienced its lowest level during a summer’s drought.”

The Arsenal’s second commander, James W. Ripley (who took over May 31, 1833), persuaded the government to add another 20 acres and extend the fence around the new area. Ripley oversaw construction of a “spring-fed reservoir” near the commander’s quarters, with a large enough pool so trout and salmon could swim in it. “Whether these delicacies were for the sole enjoyment of the commander and his officers, or whether they were shared with the enlisted men, is left to the imagination of the reader,” Peladeau and Reed wrote.

The Arsenal was a military facility until the early 1900s, when the federal government gave it to the state. It was part of the Augusta Mental Health Institute until the late 1900s.

In 2000, the Arsenal was designated a National Historic Landmark District. The on-line list of Maine’s historic places calls it “a good example of a nearly intact early 19th-century munitions storage facility.”

Peladeau and Reed’s piece was intended to help historic preservation groups decide what to do with the eight granite buildings remaining in 1997. “All in a chaste and simple style, they stand today as among the best surviving examples of the military architecture of the period,” the historians wrote.

Main sources

Hatch, Louis Clinton, ed., Maine: A History 1919 (facsimile, 1974).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.