Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Churches – Part 5

by Mary Grow

Sophia Bailey Chapel and Oak Grove School

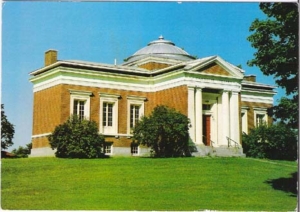

Returning to the list of churches on the National Register of Historic Places, the next to be discussed is one that readers met briefly last week. The Sophia D. Bailey Chapel, at Oak Grove School, (the school had several names; Oak Grove School is simplest) was originally known as the River Meeting House. It was where China Quakers worshipped before the East Vassalboro meeting house and then China’s own Pond Meeting House were constructed.

The River Meeting House was built in 1786; Wikipedia says it was the first religious building in Vassalboro. When they nominated it for the National Register in early 1977, historians Robert L. Bradley and Frank A. Beard listed two reasons it deserved recognition:

— It is “an unusual architectural adaptation”; and

— It is a “link with the Quaker heritage” of the Oak Grove-Coburn School, of which it was a part in 1977, and of the Town of Vassalboro.

The chapel was listed on the National Register on Sept. 19, 1977.

According to Bradley and Beard, the 1786 River Meeting House was a T-shaped wooden building, clapboarded, with gable roofs and a single doorway. It faced south onto what is now Oak Grove Road (previously North Vassalboro Road), they wrote.

Betsy Palmer Eldridge wrote in 1975 that the original building was a typical Quaker chapel, “a very plain building of white clapboard with few and simple windows.” It had no steeple or bell tower.

The building had no cellar. Inside, congregants sat in straight-backed wooden pews facing the pews from which the elders led the meeting.

Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, wrote that in 1892, Vassalboro Friends “have a large burial place in rear of their church, near the seminary,” and had also used the Nichols Cemetery, on the north side of Oak Grove Road a few miles eastward.

Vassalboro resident Susan Briggs, one of the leaders of a group seeking to preserve the chapel, wrote in an email that “there is a cemetery East of the Chapel now.” Early Vassalboro maps show two cemeteries on opposite sides of the road, she said.

“You can see where a road used to be on the north side of the present cemetery,” she continued, leading her to assume the road was relocated years ago.

There might be other Quaker graves outside the present cemetery, Briggs added. Since Quakers commonly used small, simple grave markers, “lost” graves are certainly possible.

In their detailed and often entertaining history of the Oak Grove School’s first 70 years, published in 1965 by the Vassalboro Historical Society, Raymond Manson and Elsia Holway Burleigh explained that the River Meeting House and the nearby Quaker school were separate entities until September 1895. By then, the Vassalboro Friends were too few to maintain the building, which needed major repairs.

On Sept. 19, 1895, the Vassalboro Monthly Meeting of Friends gave the chapel to what was then Oak Grove Seminary. Sophia D. Bailey, wife of Charles M. Bailey, offered to pay to have the building repaired and remodeled.

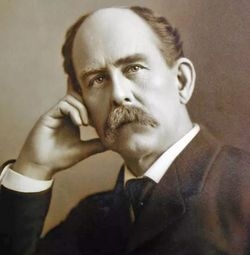

According to an undated copy of Harrie B. Coe’s Maine Biographies found on-line, Charles M. Bailey (1820-1917) established in 1844 Charles M. Bailey’s Sons & Company in Winthrop. The company manufactured floor coverings; Coe wrote that it produced some 30,000 rolls annually and had on average 65 employees. Bailey was a Quaker; his wife, also born in Winthrop, was Sophia D. (Jones) Bailey.

Kingsbury’s version is that Charles Bailey was one of two sons who, with his brother Moses (1817-1882) took over the oilcloth business his father Ezekiel started. Oilcloth, invented in Scotland in the mid-1800s, was used as an inexpensive floor covering into the 20th century, before more durable linoleum supplanted it.

A 2017 newspaper article about the effort to preserve the chapel identified Charles M. Bailey, husband of Sophia Bailey, as one of the headmasters of Oak Grove School. Manson and Burleigh’s list of Oak Grove Seminary Principals from 1850 to 1918 does not include a Bailey. (It does include eight different Joneses.)

Bradley and Beard described in some detail the 1895 “architectural adaptation.”

It resulted in a Shingle-style building with all the windows changed and relocated, two entrances and a square tower in the southeast angle of the original T. The tower was designed as a bell-tower, but no bell was provided.

The building they described in 1977 had the main doorway in the base of the tower with a partly enclosed porch with columns and arches. A second doorway at the far end of the south side had a flat arched window above it. A four-section south-facing window in the main building and a larger one in the base of the tower were also topped by arches.

Manson and Burleigh added that the work included adding a cellar to house a heating plant. The bricks for the cellar walls had been chimneys in wealthy manufacturer (and Quaker) John D. Lang’s Vassalboro mansion, donated by Hall Burleigh after he tore down the building.

Bradley and Beard wrote that there were two cellar windows on the west side, none on the east side.

The two-story tower is square, with four large arched openings in the second story above what the historians called bowed balconies. In the south side below the window and balcony is a small rose window.

Manson and Burleigh said the inside was changed dramatically, although several newer sources mention that the original ceiling survives. The traditional double row of pews that seated the group of elders facing the rest of the congregation was removed and a pulpit built.

Cane-seated chairs replaced the other pews (contemporary interior photos show that the pews are black). A carpet was laid and an organ purchased. Space was provided for a “combined Sunday school and lunch room.”

By 1895, the Quakers had given the chapel to the Oak Grove School. The renovations were designed by William H. Douglas (or Douglass), of Lisbon Falls; after Sophia Bailey funded the work, the name was changed to Sophia D. Bailey Memorial Chapel, dedicated Dec. 8, 1895.

For almost a century after 1895, the fate of the chapel was intertwined with the school’s rising or falling fortunes, which will be summarized in next week’s article in this series. Eldridge mentioned one change: in 1949, the entrance was again relocated, the driveway eliminated, and the inside repainted.

In 1970, Oak Grove School merged with Coburn Classical Institute, in Waterville, to create a high school called Oak Grove-Coburn. In 1989, the school closed for good.

In 1990 the school buildings, but not the chapel, were sold to the State of Maine and became the site of the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Proceeds from the sale created the Oak Grove School Foundation, which assumed ownership of the chapel.

Preserving a building was low on the Foundation’s priority list. Its purposes are support of education and educational innovation, especially at the high school level, and aid to charitable and religious groups.

The chapel was used for religious gatherings, graduations and other school-associated events, and after the school closed hosted weddings, reunions and other celebrations.

By 2015, the Sophia D. Bailey Chapel was on Maine Preservation’s list of critically endangered historic buildings. The Yarmouth-based nonprofit organization’s explanation for the listing said that “The Chapel is underutilized with deferred maintenance, and is falling into disrepair.”

The report cited water entering the building through both the roof and the cellar, and said that the Foundation had considered demolishing the building. In response, the Maine Preservation report said, an alumni group organized the Friends of the River Meeting House and Oak Grove Chapel to try to preserve it.

Current leaders of the effort include Vassalboro residents and Oak Grove-Coburn alumnae Susan Briggs, Jennifer Day and Jody Welch (mentioned as East Vassalboro Grange Master in the April 29 issue of The Town Line; she and her husband Bernard, who wrote part of the April 29 story, were married in the chapel in 1981).

In 2017, the Maine Community Foundation’s Belvedere Historic Preservation Grant Program provided a $7,500 grant to repair the foundation and stop further water inflow.

By 2020, the alumnae group was planning to remedy the chapel’s major deficiency, no running water and no toilet facilities. Their proposed remedy, as they explained it to Morning Sentinel reporter Greg Levinsky in November, is to build a nearby caretaker’s cottage that will provide these amenities to any group using the chapel.

They foresee renting the cottage, so it will support itself financially. In addition to providing restrooms, they plan a small kitchen available for events at the chapel and probably additional space for meetings.

Cost of the project was estimated at around $160,000 pre-pandemic. It has increased since. Last fall, Levinsky reported, an anonymous donor offered $80,000 if the Friends group could raise a matching amount.

Day said in an email that the pandemic suspended active fundraising. She now looks forward to getting a more firm estimate of construction costs and resuming activities, including small-group chapel tours.

Day pledges to “keep reinforcing the historic value of the chapel and the future relevance of the building for community events, private celebrations and cultural gatherings.”

Restoration fund information

People who would like to help fund restoration of the historic Sophia D. Bailey Chapel may make donations through Paypal to oakgrovechapel@gmail.com or send checks, made out to Friends of the Rivermeetinghouse, to Sue Briggs, 593 Main Street, Vassalboro ME 04989.

More information is available from Briggs, whose email is briggsusan@gmail.com.

Main sources

Eldridge, Betsy Palmer, Owen Hall Pamphlet June 1975.

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Manson, Raymond R., and Elsia Holway Burleigh, First Seventy Years of Oak Grove Seminary ((1965).BOX

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Personal correspondence, Susan Briggs and Jennifer Day.

Websites, miscellaneous.